Ismail Kadare — albania's Mark Twain

This week's book is the diptych “The Daughter of Agamemnon. The Successor” by writer Ismail Kadare.

This week, on January 28, it would have been the 90th birthday of Ismail Kadare — the Albanian writer who brought his country's literature into the global context and remained one of the key figures of European prose in the 20th–21st centuries for decades. His books were read as universal texts about power, fear, and memory, but they were born within the realities of communist Albania. “Realnoe Vremya” literary critic Ekaterina Petrova tells about Ismail Kadare's book “The Daughter of Agamemnon. The Successor," and why this diptych is considered one of the harshest statements about “the mental and spiritual infection of the individual by the totalitarian state.”

Continuous Balancing Act

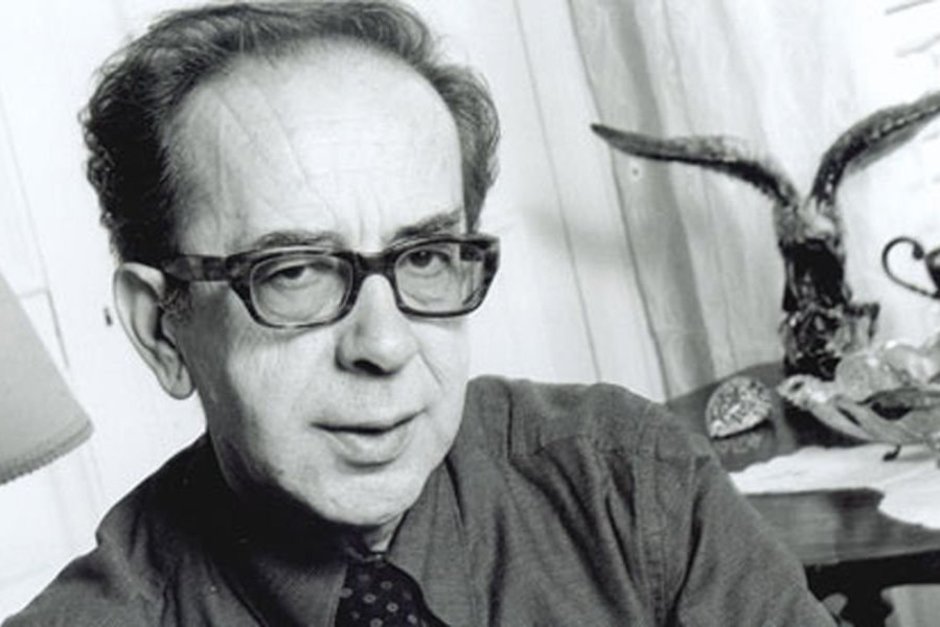

Ismail Kadare lived almost his entire adult life inside the Albanian communist regime, being neither its open opponent nor a fully loyal writer. At the same time, Kadare perceived the country's power as the harshest totalitarian regime in Europe in the second half of the 20th century. But the writer managed to create works that touched on issues fundamental to the Albanian people. Most of the writer's books were published in his homeland, which later became the basis for accusations of conformism.

In fact, Kadare's relationship with the authorities was built as a series of permissions and prohibitions. Early texts already aroused suspicion: the story “Coffee Days” (1962) and the novella “The Monster” (1965) were banned by censorship immediately after publication. These bans cemented his reputation as an author prone to “decadence” and violating socialist canons.

Particular tension arose after the international success of the novel “The General of the Dead Army” (1963). The French edition of 1970 became a turning point: the Albanian secret police recorded the irritation of the party environment, stating that “this novel was published by the bourgeoisie, and this is unacceptable.” The state security service report provides a harsher formulation: Kadare's opponents in the apparatus called him an “agent of the West," which, under the conditions of Albania under Enver Hoxha's rule, was considered one of the most dangerous accusations.

Meanwhile, within the country, the writer's status remained dual. The official press called him a “hero of the new Albanian literature” and emphasized that his work “touches on many problems concerning Albanian society.” At the same time, a number of works were either hushed up or subjected to ideological editing. A key episode was the story of the poem “The Red Pashas” in 1975. After an attempt at publication, a grand scandal erupted: the newspaper issue was destroyed, the author himself faced harsh criticism and lost the right to publish. During this period, Kadare barely avoided execution and was sent to forced labor in a remote area of central Albania.

Even texts formally aligned with the official line were used by Kadare as a means of self-preservation. The novel “The Severe Winter” (1973), dedicated to the break with the USSR, had pragmatic significance. The writer counted on the dictator not killing a person — a famous writer — who glorified him. Kadare himself later explained that he consciously endowed Enver Hoxha with traits of humanity and democracy, hoping for a “reverse influence” of the literary image on the real prototype.

By the early 1980s, the tension had reached its peak. The novel “The Palace of Dreams” (1981) was perceived as an anti-totalitarian text and considered anti-communist by the authorities, after which it was banned, although about 20,000 copies were sold before the ban. The authorities refrained from immediate repression due to the author's fame outside the country and fears of an “international reaction.”

By the time of writing “The Daughter of Agamemnon” (1985), the action of which the author sets in the 1970s, Kadare already had experience with bans, public campaigns, forced labor, and constant surveillance. His position within the regime was defined by continuous balancing between recognition and threat.

Between Albania and France

Ismail Kadare's emigration to France was a direct continuation of the crisis of trust between the writer and the Albanian communist leadership in the late 1980s. After the death of Enver Hoxha in 1985 and Ramiz Alia's rise to power, a process of regime liberalization began in the country. However, Kadare was disappointed with the slow pace of change and lost faith in the readiness and ability of Albania's communist leadership to produce a real dismantling of the dictatorship.

The decision to leave was made against the backdrop of the 1989 events in Eastern Europe. Albanian authorities were frightened by the revolution in Romania, after which, in 1990, they made serious concessions in economic and political spheres. For Kadare, these measures proved insufficient. In October 1990, he requested political asylum in France.

Kadare publicly criticized the Albanian government, called for the democratization of isolationist Albania — Europe's last communist country — and as a result, faced the wrath of the authorities and threats from the Sigurimi secret police. The writer was convinced that “more than any action [he] could undertake in Albania, [his] escape would help democratize [his] country.”

The reaction from official structures was immediate. The Albanian state news agency issued a statement calling what happened an “ugly act” and accusing the writer of “placing himself in the service of Albania's enemies.” At the same time, part of the Albanian intelligentsia, taking serious personal risks, publicly supported Kadare. In particular, the chairman of the Albanian Writers' Union, Dritëro Agolli, stated: “I continue to have great respect for his work.”

It is noteworthy that even after Kadare received political asylum, his books in Albania were not completely banned, and he remained a popular and recognized author. In the West, he was considered a national figure, comparable in popularity to Mark Twain in the United States. And a journalist from The New York Times claimed that “there is hardly an Albanian house without a book by Kadare.”

The emigration itself was relatively brief in its formal status. Rapid political changes in Albania in late 1990 — early 1991, which led to the introduction of a multi-party system, limited the period of Kadare's actual emigration to a few months. Subsequently, he began living both in France and Albania. Nevertheless, it was the French period that proved key for publishing texts previously impossible within the country. Starting from 1991, Kadare published works that could not see the light earlier for political reasons, including the novels “The Shadow” and “The Daughter of Agamemnon," which he had smuggled out back in 1986.

After receiving asylum, Kadare continued to write, and his Parisian exile proved fruitful, allowing him to work in both Albanian and French. Already in 1992, the novel “The Pyramid” was published, and in 1994, the writer began work on the first bilingual collected works with the Fayard publishing house. This period cemented France's status as not only a place of political asylum but also Kadare's main literary platform in the post-communist era.

“Infection of the Individual by the Totalitarian State”

The novel “The Daughter of Agamemnon” was written in the mid-1980s, in the final years of totalitarianism in Albania. It was a direct critique of the Albanian repressive regime. The text could not be published within the country: the manuscript was secretly taken abroad with the help of French publisher Claude Durand and saw the light only in 2003. According to Kadare's plan, this novel was to appear only in conjunction with its sequel — “The Successor.”

This short novel was among three texts that Kadare managed to secretly transport out of Albania shortly after Enver Hoxha's death. The first pages were disguised as Albanian translations of works by Siegfried Lenz, after which Claude Durand came to Tirana and took out the remaining parts. The publisher himself placed the manuscripts in a safe deposit box at Banque de la Cité in Paris. The translation into French was done by violinist Tedi Papavrami from the original, unedited manuscripts, and the first edition appeared in France in 2003, after Kadare had already written the sequel — the novel “The Successor.”

The action of “The Daughter of Agamemnon” unfolds in Tirana on the day of the May Day parade. The story is told in the first person — by an unnamed television journalist who unexpectedly receives an invitation to the party tribune. It's the annual May Day parade, almost exclusively aimed at glorifying the country's leader. At the same moment, his beloved Suzana breaks off the relationship, explaining that her father — the appointed successor to the supreme leader — cannot allow his daughter to be involved with an unsuitable person. Because the chosen one is a passionate liberal who is sharply (though privately) opposed to the regime and recently experienced a purge at television, as a result of which two of his colleagues were demoted.

Formally, the plot is limited to one day, but the structure of the text is an internal monologue accompanying the hero's journey to the stadium. It is a peculiar collection of notes on human destruction — a small hell in which the narrator successively meets victims of the regime. Among them are a neighbor whose scientific career ended after he allegedly laughed loudly on the day of Stalin's death; a theater director exiled to the provinces for a play with thirty-two ideological errors; and a figure with the initials T.D., who survived several purges. The latter is compared with a character from an Albanian parable about a man eating his own flesh while an eagle carried him out of hell.

The central semantic node of the novel became the juxtaposition of Suzana's fate with the myth of Iphigenia. The title itself associates the Successor with Agamemnon, Suzana with Iphigenia, and her sacrifice with the sacrifice of Agamemnon's daughter. This parallel is stated directly in the text:

I would never have thought that the instantly arisen resemblance between Suzana and Iphigenia, one of those quick flashes, bright and fleeting, that flicker in the human brain thousands of times a day, would grow in my mind into a complete identification. The identity was so complete that if I heard a phrase like “Suzana, daughter of Agamemnon, etc.” on the radio or television, it would seem more than natural to me.

As a key source for the hero's reflections, Robert Graves's book “The Greek Myths” appears several times, helping him connect the modern political situation with the ancient plot.

The analogy extends to recent history as well. The novel directly mentions the fate of Yakov Dzhugashvili, son of Joseph Stalin. Stalin, according to the narrator's logic, sacrificed his son not for the common fate of a soldier, but to obtain the right to demand the life of any other. The same sacrificial formula applies to Suzana and her father. It becomes a story of victims of a tyrannical cynical trick, serving to legitimize future violence.

After its publication in 2003, “The Daughter of Agamemnon” was published together with the novel “The Successor” as a single diptych. Kadare's French publisher Claude Durand called it “one of the most complete and outstanding works of Ismail Kadare.” Literary critic James Wood characterized the novel as “perhaps his greatest book” and as one of the harshest texts about “the mental and spiritual infection of the individual by the totalitarian state.”

“Enemy of the State”

The novel “The Successor” is the second part of the diptych. This work directly relies on real events related to the death of Mehmet Shehu in December 1981. In the official version of the Albanian authorities, Shehu committed suicide, but the subsequent declaration of him as a “multi-agent foreign spy” and the repression against his entire family gave rise to persistent doubts about this version.

The historical prototype of “The Successor” is the second man in the Albanian party-state hierarchy, the closest associate of Enver Hoxha, and prime minister from 1954 to 1981. After a conflict with Hoxha in 1981, Mehmet Shehu died. According to the official announcement, he “committed suicide in a state of deep mental agitation.” Shortly after his death, accusations of spying simultaneously for Yugoslavia, the USSR, the USA, and Italy followed, and then large-scale repression against relatives and associates, including executions of top officials of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Sigurimi (the state security organ in Albania). In Kadare's novel, these facts are transformed into a literary chronicle of the fall of the Successor's family after his posthumous transformation into an “enemy of the state.”

Compositionally, “The Successor” is built as an investigation that from the very beginning lacks the prospect of a final answer. The novel opens with a message:

The Successor was found dead in his bedroom at dawn on December 14. At noon, Albanian television broadcast a brief announcement: on the night of December 13–14, the Successor committed suicide by shooting himself as a result of a nervous breakdown.

Kadare begins with an apparent accident that allows the author to explore competing explanations. The novel poses the key question for the book: when did this begin? When did the “accident” become inevitable?

The novel sequentially expands the narrative field: from official versions and rumors — to the private voices of participants and witnesses. The final chapters are narrated in the first person by an architect who knew about a secret underground passage between the houses of the Leader and the Successor, and by the Successor himself, already after death. This technique turns the novel from a parody of a detective story into a chronicle of the fall of the remaining family, when, after the posthumous condemnation of the Successor, all his relatives are interned, and the story of “The Daughter of Agamemnon” returns in Suzana's testimonies during interrogations.

The novel does not solve the mystery of the death, but does not leave any rumor unvoiced, including versions of suicide, murder on the Leader's order, and the role of the inner circle. As a result, “The Successor” captures not the outcome of the investigation, but the very impossibility of knowledge under a totalitarian system, where preference is given to maintaining a state of uncertainty rather than establishing the truth.

“A Great Storyteller”

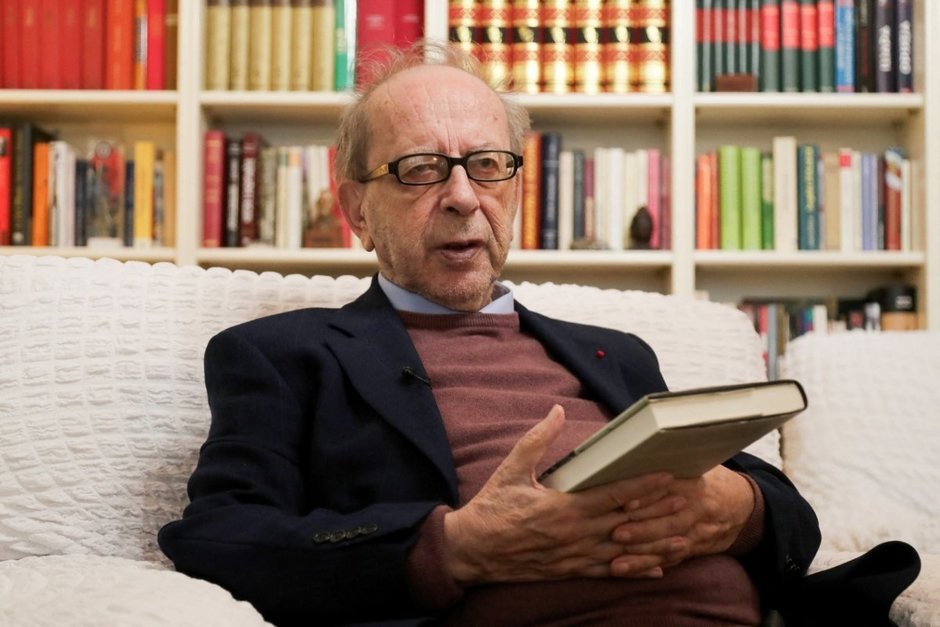

In the last decades of his life, Ismail Kadare existed in a mode of dual presence — between France and Albania. In the 1990s–2000s, Kadare remained an active public figure, although he fundamentally refused direct participation in politics. He was asked several times to run for president of Albania by representatives of both of the country's largest parties, but he always refused. Meanwhile, Kadare's authority in the country and abroad only grew.

During this period, he published novels “The Pyramid," “The Spirit," “The Cold Flowers of March," “The Life, Game and Death of Lul Mazrek," and later — “Crazy Things," returning the reader to childhood memories and the world of “Chronicle in Stone.” In 2020, the semi-autobiographical novel “The Doll” was published, dedicated to the writer's relationship with his mother and country.

International recognition for Kadare in these years acquired an institutional character. He received the Prix mondial Cino Del Duca (1992), the International Booker Prize for a body of work (2005), the Prince of Asturias Award (2009), the Jerusalem Prize (2015), the Neustadt International Prize for Literature (2020), and the American Prize for Contribution to World Literature (2023). In 1996, Ismail Kadare became a lifetime member of the French Academy of Moral and Political Sciences, taking the seat vacated by Karl Popper's death. In 2016, he was awarded the Legion of Honour, and in 2023 he received the highest degree of this order — Grand Officer — by special decree of the President of France.

The features of his literary method in later years did not change. Kadare's English translator David Bellos wrote:

The main and decisive reason for reading Ismail Kadare is that he is a great storyteller. He tells amazing stories — and tells a lot of them.

Bellos compared Kadare to Balzac, clarifying that if the latter “limited himself to one place and one time," Kadare “takes us everywhere: to ancient Egypt, modern China, the Ottoman Empire, Moscow, and Western Europe.” At the same time, Kadare himself repeatedly said that readers “should not pay too much attention to context," because his way of telling stories “has not changed one iota in sixty years," despite radical changes around him.

Bellos also noted the stable elements of this world: the constant presence of ancient Greek myths about power and family feud, Balkan folklore plots, the exploration of the connection between personal and political, and the characteristic “weather," which functions “almost as a separate character” and serves as a marker of distance from socialist realism. Kadare used these techniques, by his own admission, as a means of survival inside a system where “for one word against the regime they might not convict you, but shoot you.” Historian Henri Amoroux emphasized that, unlike Soviet dissidents who published after de-Stalinization, Kadare wrote and published in a country that remained totalitarian until 1990.

In his final years, Kadare returned to Albania. He died on July 1, 2024, in a Tirana hospital from cardiac arrest at the age of 88. He was given a state funeral at the National Theater of Opera and Ballet, after which a private burial took place. Albania declared two days of mourning, Kosovo — one day. By the time of his death, Kadare had been nominated for the Nobel Prize fifteen times, and, as he ironically noted himself, many thought he had already received it.

The book “The Daughter of Agamemnon. The Successor” holds a special place in the Albanian writer's legacy: it combines personal experience of living next to power, a mythological framework, and documentary memory of key events in Albanian history at the end of the 20th century. Kadare's later path shows the resilience of the world he created, which, in David Bellos's words, “arose fully formed at the very beginning” and over the decades merely unfolded in new fragments.

Publisher: “Ivan Limbakh Publishing House”

Translation from Albanian: Vasily Tyukhin

Number of pages: 288

Year: 2026

Age restriction: 16+

Ekaterina Petrova is the literary critic of the online newspaper “Realnoe Vremya," host of the Telegram channel “Poppy Seed Buns.”