Sergey Diaghilev — «a genius milkman of the European bourgeois elite»

The host of the «Breakfast with Diaghilev» project and a theatre journalist discussed the book «The Diaghilev Empire» by Rupert Christiansen, as well as its main character — the impresario Sergey Diaghilev, who «turned the art world upside down».

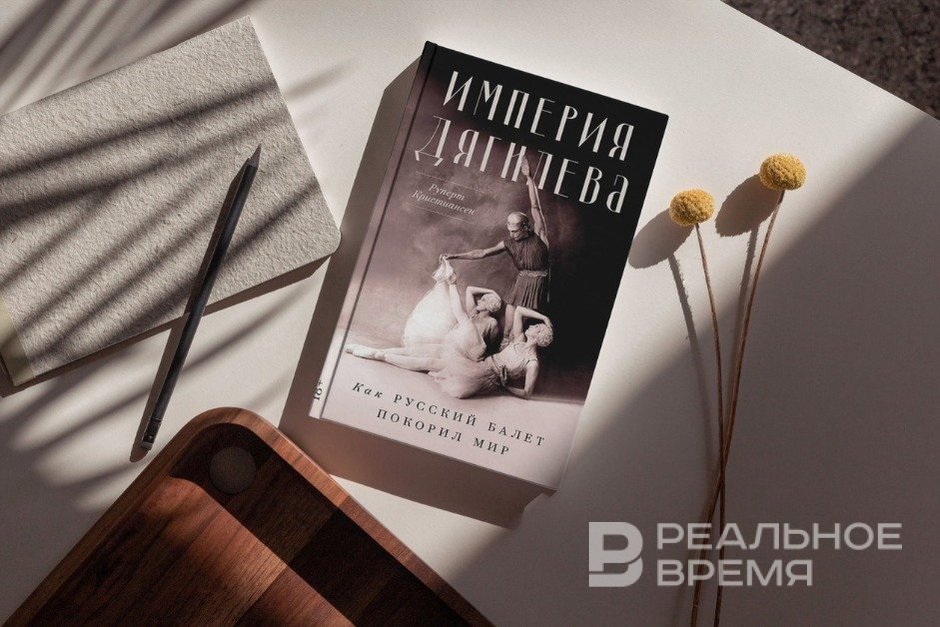

In November 2025, the book «The Diaghilev Empire» by British cultural historian Rupert Christiansen was published by Alpina Non-Fiction. On January 24, the book was presented at the Des Esseintes Library in Moscow. The book was presented by Anna Galaida, the scientific editor of the publication, and Maria Druzhinina, an independent researcher and author of the «Breakfast with Diaghilev» project. They discussed why the figure of Sergey Diaghilev still defies final classification, how he worked with artists and composers, and what the production logic of the «Russian Seasons» was, which determined the development of world ballet in the 20th century. The details are in the report by Ekaterina Petrova, a literary reviewer for «Real Time».

Diaghilev, who didn’t like ballet

«It’s unexpected that so many people wanted to discuss a book on a topic that has already been the subject of dozens, if not hundreds, of studies», said Anna Galaida, the scientific editor of Rupert Christiansen’s book «The Diaghilev Empire», a theatre journalist and the leading editor of the literary and publishing department of the Bolshoi Theatre, at the beginning of the meeting. She emphasised that Rupert Christiansen’s book does not claim to make sensational discoveries, but it significantly supplements the existing understanding of the Diaghilev world.

Galaida recalled that half a century ago, the name of Sergey Diaghilev was virtually banned in the USSR, information about him was disseminated fragmentarily, and the topic only returned to cultural circulation in the 1980s. «Decades have passed since then, but this figure has not become fully understood and classified: the more we learn about him, the more debates and discussions he provokes», Galaida said.

Anna Galaida described Diaghilev as a figure significant beyond national and genre boundaries: «Today we can say that he was a person who turned the art world upside down. He does not belong only to Russia or only to Europe. Now we understand more clearly how our time is connected to him». This scale, she said, sustains a steady interest in new research and interpretations.

Animation director, screenwriter, independent researcher and author of the «Breakfast with Diaghilev» project, Maria Druzhinina, is studying the early, «Russian» period of Sergey Diaghilev’s activity. She recalled that his journey did not begin with ballet: he was associated with the «World of Art» association, exhibition and magazine projects. At the same time, interest in ballet, she said, appeared as early as the late 1890s, although the genre itself was not a priority for him for a long time.

Galaida clarified this point more sharply: «In general, Diaghilev didn’t really like ballet and didn’t really acknowledge it until a certain point. He focused on ballet because he saw it as a concentrated art form in which different types of art could be combined». Druzhinina agreed, adding that in his later years, Diaghilev tried to move away from ballet and became more interested in books.

Speaking about his role in the artistic process, Druzhinina formulated a position close to the logic of the author of the book «The Diaghilev Empire», Rupert Christiansen: «Diaghilev doesn’t invent — he does. He brings together people who then start to invent and create together. He is a catalyst that speeds up reactions and allows them to begin». According to her, this initiating function explains his influence, despite the constant debates about whether he can be considered a creator in the traditional sense.

The scientific editor of the book, Anna Galaida, in turn, insisted that the deeper his activities are studied, the more obvious his authorial role becomes. «He didn’t put together an enterprise for the sake of money or commercial success. He had his own vision of art and sought co-authors to воплотить it», she emphasised. Recalling Sergey Diaghilev’s musical and literary pursuits, Galaida noted that he was not an outstanding performer in them, but he found an area in which he was truly great: understanding what modern art should be and in what direction it should develop.

A separate topic of discussion regarding Diaghilev’s persona was his manner of working with artists and composers. Galaida cited examples from the memoirs of Igor Stravinsky and Sergey Prokofiev: «In their diaries, it is regularly mentioned that Diaghilev ordered the score to be shortened, numbers to be removed, and certain elements to be added. He deeply involved himself in the process and was to some extent a co-author». The lack of clearly defined copyright, she said, later became the cause of acute conflicts reflected in memoir literature.

Druzhinina supplemented this image with a specific episode from correspondence with Rimsky-Korsakov, which illustrates Diaghilev’s method: «He heard ‘no’ many times, and then wrote: ‘Well, in general, it will be as I said’. And in response, he received a visiting card from Rimsky-Korsakov with the inscription: ‘Off we go, said the parrot, as the cat dragged him up the stairs’». Galaida also recalled the ballet «Scheherazade», created from Rimsky-Korsakov’s music, which was not intended for ballet and was reworked without the consent of the composer’s heirs: «The ballet is still performed in the sequence that Diaghilev envisioned». This example, according to Galaida, shows the scale of Sergey Diaghilev’s influence and the degree of responsibility he took upon himself in shaping the artistic result.

Diaghilev, who became a producer

Diaghilev is one of the first producers in the sense we attribute to this profession today. «Whatever name from his era we take, almost all of them turn out to be connected with Diaghilev. Whether a performance was successful or not, they were all drawn into his orbit», emphasised Anna Galaida. According to her, if an artistic name succeeded, its connection with Diaghilev was almost inevitable, while those who «showed great promise but never delivered» often found themselves outside his projects. In this regard, Galaida listed the French composer Claude Debussy, playwright and film director Jean Cocteau, composer and director Darius Milhaud, and fashion designer Coco Chanel, noting that they were all «collaborators» of Diaghilev at different times.

Galaida separately addressed the common perception of Sergey Diaghilev as a wealthy patron. «Diaghilev is not a money bag who provided a beautiful presentation of Russian ballet», said Galaida, recalling that his upbringing took place during his family’s ruin and that he lived his whole life under conditions of constant lack of money. According to her, Diaghilev knew how to find large sums, but he spent them not on himself: «He was a genius milkman of the European bourgeois elite, but he invested that money precisely in the art he loved and believed should exist in his era».

Maria Druzhinina supplemented this image by calling Diaghilev the creator of the producer profession. «Diaghilev is considered the inventor of the producer as a person who makes creative decisions», she noted, comparing this role with the modern concept of a creative producer. At the same time, Druzhinina emphasised the discrepancy between the function and the lifestyle: «He didn’t amass a fortune, he had a small collection of books and a few paintings, but in the usual sense of luxury, he didn’t have it». Unlike later figures who used success to create personal projects and infrastructure, Diaghilev, according to her, «didn’t physically build anything».

Galaida clarified the everyday aspect of this producer existence: «He didn’t own apartments or cars and lived in hotels all his life». The topic of money inevitably led to discussions of accusations of non-payment of гонорары, which often accompany Diaghilev’s name. Druzhinina recalled that such accusations are not always supported by documents. According to her, conflicts over money are typical for a producer’s position when the expectations of project participants and real possibilities do not coincide.

Anna Galaida, in turn, noted the economic effect of the Diaghilev system: «He may not have always paid his authors in full, but he drove up their rates in the market so that everyone else paid them, and their гонорары soared to unimaginable heights if they were successful with Diaghilev». This mechanism, she argued, was an integral part of Diaghilev’s producer practice and determined the further career of many participants in the «Russian Seasons» — Diaghilev’s theatrical enterprise with tours of artists from the Imperial theatres of Moscow and St. Petersburg from 1908 to 1921.

Diaghilev, whom we will see in the book

Rupert Christiansen’s book «The Diaghilev Empire» was published in the UK in 2022 and was initially perceived by Anna Galaida as just another study among numerous works about Diaghilev. «Given the volume of reading I’ve done on this topic, it seemed to me that this wasn’t a priority book», she explained. The situation changed when the Alpina Non-Fiction publishing house offered her to become the scientific editor of the Russian edition and carefully read the translated manuscript. «I thought it would be a fairly quick and easy job for me. As it turned out, I was deeply mistaken», said Galaida, noting that working with the text took much longer than expected by both her and the publisher.

According to her, thoroughness was заложена at the translation stage: «I think both the book and the publishing house were very lucky with the translator, Elena Bortkevich, because you read the text not as a study or monograph, but primarily as a novel». At the same time, Galaida emphasised that this is not about fictional storytelling, but about the way of writing: for Christiansen, historical figures are living people. «He perceives Diaghilev, Benois, Fokine, Bakst, Nouvel as living people, with their personal and artistic relationships, and that’s why he has biases», she explained. These discrepancies with established assessments, including those regarding actor Marius Petipa or ballerina Anna Pavlova, caused serious disputes between the scientific editor and the text, but were eventually accepted as part of the author’s perspective.

Galaida separately noted Christiansen’s methodological position: «He honestly admits that he is not a ballet expert or ballet critic. He views this phenomenon from a cultural studies perspective, and the overall picture is important to him». This, she said, is what gives the book its value, given the chosen angle of view. Anna Galaida emphasised that Christiansen shows Diaghilev «not quite the way he has already managed to take shape in the conventional perception».

Speaking about the content, Maria Druzhinina emphasised that Christiansen avoids simplistic formulas like «The Russian Seasons changed the world», and instead consistently shows a system of connections. According to her, it is fundamentally important that the author looks at history from the outside: «He is English, he enters this history from England and exits through English ballet. This is an outside perspective, and that’s why he doesn’t exaggerate the influence — he can be trusted».

Druzhinina also noted the scale of the geography that Christiansen constructs: Europe, America, England, South America, Australia. For Druzhinina, the analysis of the consequences was also important: «It’s very interesting to see what happened after Diaghilev’s death, as well as the story of the competitors who quit, parted ways, and continued to work, spreading these connections».

Concluding the discussion about the book, both speakers essentially agreed on the assessment of the scale of Diaghilev’s influence. Galaida formulated it this way: «If we dig into any figure of the ballet world of the 20th century, we inevitably come across someone from the artists, teachers, or choreographers of the Russian ballet of the early 20th century. It was a system in which the words ‘ballet’ and ‘Russian’ became synonyms». She recalled that names like Vera Zorina (real name — Eva Brigitta Hartwig), Anton Dolin (real name — Sidney Francis Patrick Chippendall Healey-Kaye) or Alicia Markova (real name — Lillian Alice Marks) were stage names, and the choice of a «Russian» identity was a professional necessity. It is this long chain of consequences — from Diaghilev to the global ballet map of the 20th century — that Christiansen makes the subject of his research.

Age restriction: 18+

Ekaterina Petrova is a literary reviewer for the online newspaper «Real Time» and the host of the Telegram channel «Buns with Poppy Seeds».