The dry cleaner's parable

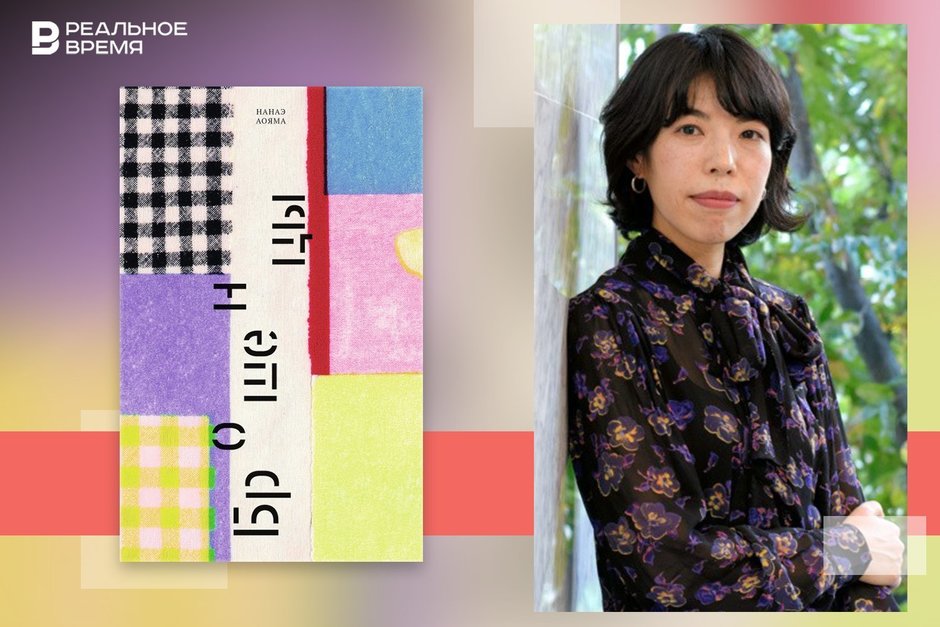

The novel “The Left-Behinds” by Japanese writer Nanae Aoyama is a story about people who become superfluous in the comfort system

Starting from the mundane detail of dry cleaning work, writer Nanae Aoyama has constructed a parabolic story in her novel “The Left-Behinds” about unclaimed things, people, and anxieties that society prefers to temporarily “place in storage.” This text reads as an attempt to capture the structure of a world where comfort is maintained through the exclusion of the superfluous, and care easily turns into a system of selection. Literary critic Yekaterina Petrova of “Realnoe Vremya” explains how a question about forgotten clothing grew into a large-scale parable-novel and why the figure of the “left-behind” has become key to understanding contemporary Japanese prose.

“Depicting the Flow of Life”

Nanae Aoyama is a Japanese writer, winner of the Ryūnosuke Akutagawa and Yasunari Kawabata literary prizes. She was born on January 20, 1983, in Saitama Prefecture, and graduated from the University of Tsukuba with a degree in Library and Information Science. Her books have been translated into Chinese, Korean, Vietnamese, German, French, English, Italian, and Polish.

Aoyama's literary debut came in 2005: her novella “Light in the Window” won the Bungei Prize—a competition focused on discovering young talents. At the time the results were announced, Nanae was 22 and working as an office employee. In 2007, Aoyama received the Akutagawa Prize for her novella “A Good Day Alone.” The judging committee described the work itself as a text “depicting the flow of life.” The book tells the story of a young woman living with an elderly distant relative and trying to find her own form of independence. When the results were announced, Aoyama was working for a travel company in Tokyo's Shinjuku district. After winning the prize, the writer left office work and focused on literature.

In 2009, the short story “A Fragment” earned Aoyama the Yasunari Kawabata Literary Prize. The writer became the youngest author in the history of this award. Later came her first major novel “My Boyfriend” (2011) and the children's book “I am the Moon Rabbit," created in collaboration with illustrator Satone Tone.

Aoyama loved reading from childhood. In one interview, she said that in the third grade she “became engrossed in the British writer Blyton's series 'The Naughtiest Girl,' borrowed the books one by one from the school library, and memorized all the characters' names.” According to Aoyama, it was then that the feeling solidified for her that the entrance into the world of books had begun at that moment. In the same conversation, she noted that she was not at all considered a child who “wrote texts well," so those around her were surprised by her career choice.

Rereading all her texts about ten years after her debut, Nanae Aoyama came to the conclusion that regardless of formal differences, she is again and again interested in “one-on-one relationships” and situations where “the boundaries between self and other blur.” The writer connects the persistence of this motif to her early reading of “The Naughtiest Girl” and the pair of characters Pat and Isabel, calling them an important starting point for her own writing.

A little later, Aoyama avidly read books by Françoise Sagan and Kazuo Ishiguro. The impulse to write came from Sagan's book “Bonjour Tristesse," read in high school. Literary scholar Judith Pascoe suggested that Emily Brontë's novel “Wuthering Heights” also influenced Aoyama's works, particularly the text “Intertwined Threads.” Later, the writer confirmed this in a personal conversation with the researcher.

The Fate of the “Left-Behinds”

Nanae Aoyama's novel “The Left-Behinds” arose from a mundane question: “What happens to clothes that are taken to the dry cleaner but never picked up?” Aoyama explained that dry cleaners had long attracted her attention as spaces of everyday care: “I have liked dry cleaners for a long time... you can feel the employees' effort to make this place pleasant.” The impetus for the idea was a specific visual cue—a notice in the shop: items not collected on time are sent to storage, and retrieval is only possible for an additional fee. This formal text triggered a chain of questions: “If no one comes for them, what will become of them? How much clothing accumulates in storage?”

These reflections coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. Aoyama connects the development of the idea to this period: anxiety, she says, did not disappear but was “as if temporarily placed in storage," and at some point “someone turned the key to the storage locker of anxiety, and it began returning to people.” This metaphor became the constructive basis for a long novel that starts with a question and moves into unexpected development. At the same time, the text itself is structured as a parable.

The plot of “The Left-Behinds” revolves around a woman named Yuko, who works at a suburban branch of the chain dry cleaner “Shell.” Her duties are standard: accepting clothes from customers, sending them to the factory, issuing finished items. Only one colleague is constantly in the shop with her—the experienced employee Wataya, who has worked there for over twenty years. It is Wataya who introduces the local term for unclaimed items: she calls them “left-behinds”—this is how items that are not collected for a long time and are then packed by dry cleaner employees and sent to storage are denoted in the text.

The turning point comes when the storage facility returns boxes with such items back to the shop with the explanation that there is no free space. Wataya hands the box to Yuko so she can somehow dispose of these “left-behinds.” Yuko takes the clothes home, and the next morning discovers that all these items—ties, blouses, jackets, trousers, scarves—are worn on her all at once.

As it turned out, on me was not only a tie, but also two synthetic blouses, a mouse-colored jacket, brown trousers, a sage-green skirt, and a red plaid scarf—all these items covered my body in a thick layer.

After this, the clothes literally begin to lead Yuko. She leaves the house and, as if pulled by the garments, finds herself on a journey. The woman tries to return the clothes to their owners. One episode involves a purple tie: Yuko finds the house of the presumed owner but is refused—the item is declared unnecessary and not even related to the owner's memory, with an explanation that it was bought by the wife who left the home. In other cases, the reaction to the “left-behinds” is even harsher. Some said the sight gave them chills, others pushed their colleague aside and ran for the exit.

As a result of searching for the owners of the clothes and wandering around the city, Yuko meets other people—men, women, married couples—who are in the same state. They are all dressed in layers of others' unclaimed clothing and moving in the same direction, towards a certain “storage facility," the exact location of which is unknown. It is only known that trucks with boxes periodically go there.

The sudden mass return of the “left-behinds” looked quite anomalous, so the characters decided that something had happened, and perhaps was still happening, at the storage facility. The journey to the storage facility took an indefinite amount of time and passed through nights spent outdoors, internet cafes, roadside shops, and residential areas.

If you go into the district, I think you can find a cheap hotel or internet cafe. Of course, you can spend the night at a convenience store or even a family restaurant, but you can't lie down there, and sitting all night is quite difficult. So I myself sleep outdoors.

“An Empty Train on the Tracks”

The novel “The Left-Behinds” is built around the question: why don't the owners pick up their things? The writer said: “There are many things that are a pity to throw away, but you don't want to see them, so they are simply distanced from oneself," including “shameful memories” and “experiences of failure.” Here it is not only about private experience but also about the mechanisms of a society that, according to Aoyama, strives for tranquility by “pushing away the anxious and thereby continuing to function.”

This premise is connected to the structure of the novel's world. Aoyama speaks of fear and a sense of complicity: “In this society, there are many parts that work precisely because the anxious is pushed aside... behind the calm lies distress, and there are people suffering there.” The writer does not offer a solution: she separately notes the value of the very fact of preservation—even if there is no clear way out.

Structurally, the novel is divided into two parts: “The Journey” and “The Storage Facility.” The text begins as easily readable prose but then becomes increasingly surreal, and the second half unfolds like an avalanche. This shift is not a genre device but a feature of the composition, which leads to a new institution that has arisen in place of the storage facility. This is a place that unconditionally accepts those prone to falling out of harsh reality, providing one hundred percent comfort. The characters are met by shining, happy people, offered to do the thing they love and that suits only them, assured that there is no place for anxiety or worries here, and that to return, one only needs to immerse oneself in warm water and rest.

But in this prosperous world, there are also “unnecessary ones”—clothing and people who become fuel for maintaining the system. What is called “rebirth” inside is, in fact, destruction. At this point in reading the book, a feeling of inexplicable discomfort arises, which grows as the characters stay in the space of the storage facility.

Things in the novel should not be understood literally. Yuko perceives them as her doubles, equally forgotten and abandoned by everyone. Linguistic metaphors emphasize this deep feeling of loneliness. For example, when Wataya reflects on responsibility, she compares herself to “a train packed with passengers," and Yuko to “an empty train on the tracks.” Another important image is the “hole," which Wataya uses to denote bags for accepted items. Over time, the “hole” ceases to be a utilitarian term and begins to point to voids in the human heart, traps, and the desire to look away from one's own flaws.

The theme of loneliness and uselessness is one of the key ones for all contemporary Japanese prose, especially women's. In “The Left-Behinds," Nanae Aoyama conveys it in the form of a parable with a fantastic world structure, seasoned with materialism and conversations about repression, preservation, and how anxiety works—at the level of private life and within social systems.

Publisher: NoAge

Translated from Japanese by: Elena Baibikova

Number of pages: 352

Year: 2025

*Age rating: 16+*

Yekaterina Petrova is a literary critic for the online newspaper “Realnoe Vremya” and the host of the Telegram channel “Buns with Poppy.”