About Evil Trolls, Abducted Maidens, and Magic Items

The first Russian edition of «Swedish Folk Tales» collected by Gunnar Ulof Hylten-Cavallius and George Stephens in the 19th century.

While in Russia children were frightened by Baba Yaga and Koschei the Immortal, evil witches and water spirits, in Scandinavia their place was taken by trolls. The collection «Swedish Folk Tales», compiled by Gunnar Ulof Hylten-Cavallius and George Stephens, was published in the mid-19th century. At that time, the systematic collection of folklore was just beginning in Scandinavia, as well as around the world. The literary reviewer of «Real Time», Ekaterina Petrova, tells who Hylten-Cavallius and Stephens were, how they collected tales, and how the image of the evil troll transformed.

The Box Opener

The contribution of Gunnar Ulof Hylten-Cavallius and George Stephens to the fixation and publication of fairy tale material is comparable to the work of the major European folklorists: the Brothers Grimm in Germany and Alexander Afanasyev in Russia. The translator of the collection of tales, Anastasia Tishunina, emphasized in the preface that «thanks to their selfless work, many wonderful Swedish folk tales have been preserved». The Russian edition is the first translation of this corpus of texts, previously unknown to the Russian reader, although in Sweden it has long been considered fundamental.

Swedish folk tales themselves are stories that were current and recorded in Sweden, some of which are connected with local history and legends. Many plots have parallels in neighbouring countries, primarily Norway, and are part of the общеевропейский (pan-European) fairy tale fund. These texts not only described the typical «impossible tasks» of folklore, which require miraculous help, but also influenced subsequent Swedish literature, including authors who directly spoke about their childhood experience of reading folk tales. Among them are Astrid Lindgren and Selma Lagerlöf.

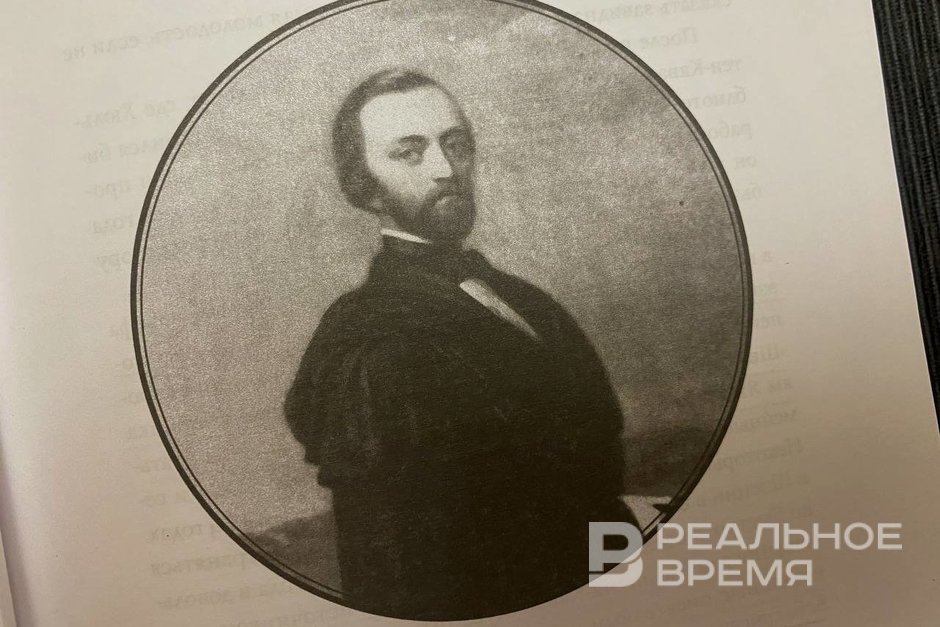

Gunnar Ulof Hylten-Cavallius (1818–1889) was born in Visby, a small town in southern Sweden, into the family of a priest, Carl Fredrik Cavallius, and Anna Elisabeth Hyltenius. Gunnar Ulof composed his surname at the request of his grandfather as a combination of his parents' names. He was educated as a philosopher, graduated from Uppsala University in 1839, and in the same year entered the service of the Royal Library in Stockholm, where he worked for seventeen years. His later career included work as the director of the royal theatres and diplomatic service: in 1860–1864, he was chargé d'affaires at the court of the Brazilian Empire.

The decisive factor for Hylten-Cavallius's turn to folklore was his acquaintance at the age of seventeen with the four-volume collection «Swedish Folk Songs» (1814–1816), compiled by Erik Gustav Geijer and Arvid August Afzelius. In his memoirs «From My Past Life», Hylten-Cavallius recalled this reading as follows:

«The depth of the feelings permeating this ancient poetry captivated me with astonishing force».

After that, he began to independently collect tales, legends, riddles, proverbs, and songs, focusing primarily on the cultural heritage of Småland, a historical province in southern Sweden. His first scholarly work was the two-volume «Dictionary of Värend», which he worked on in 1837–1839, simultaneously recording the dialect and oral stories of the region.

The work of collecting texts continued in Stockholm: Hylten-Cavallius described how he questioned peasants who came to work, treating them to beer or coffee, and meticulously recorded the tales and legends he heard, noting that the storytellers «opened up like boxes». In the fall of 1839, he met George Stephens, and their common interest in folklore quickly grew into close collaboration. Hylten-Cavallius also became one of the founders of the Swedish Association of Antiquities and created the first regional museum in the country — the Småland Museum in Växjö, based on his collections.

The Collectors of the Swedish Land

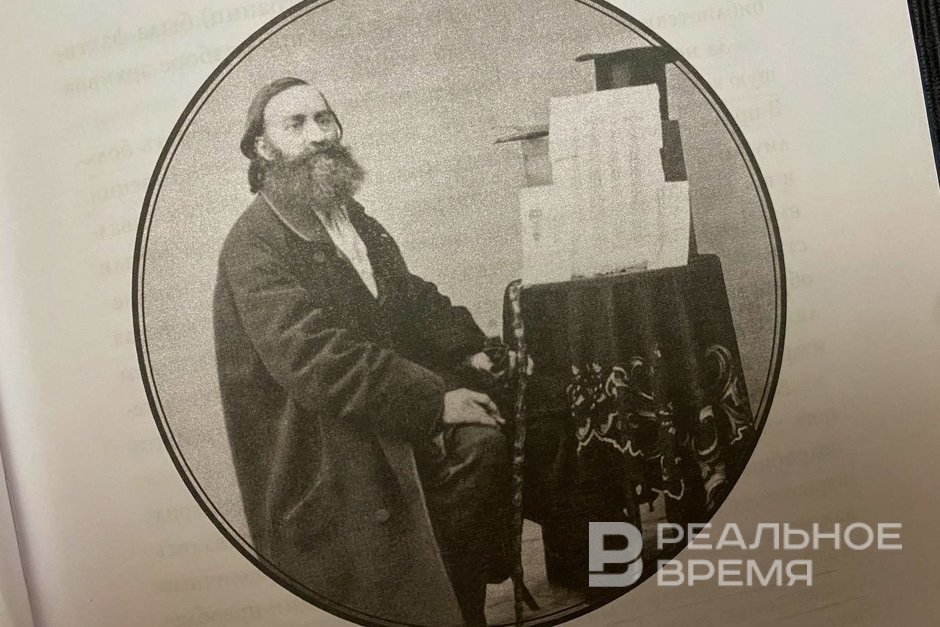

George Stephens (1813–1895) was born in Liverpool into the family of a priest and received his education at University College London. In 1834, he married Mary Bennett and moved to Sweden, where he engaged in historical and archaeological research and from that moment lived mainly in the Scandinavian countries. His main areas of scientific interest were the history of the Viking Age and runic writing: Stephens published a number of works on the runic stones of Scandinavia and works devoted to the relationship between English and the Scandinavian languages.

Along with archaeology and philology, Stephens was actively involved in literature. He studied Old Norse sagas, ballads, and legends, and also translated contemporary Swedish authors into English. His most famous translation was «The Saga of Frithiof» by Esaias Tegnér, published in England in 1839 with illustrations and detailed comments. Tegnér himself assessed the publication ambivalently, noting:

«The translation is faithful. But with translations, it's like with wives: the faithful ones are rarely beautiful».

During this period, Stephens increasingly turned his attention to folklore, and it was Hylten-Cavallius who «infected» him with an interest in folk tales of a later period. Their collaboration was accompanied by a long-term friendship and active correspondence. In 1851, Stephens moved to Denmark and was appointed a teacher of English language and literature at the University of Copenhagen, where he later received the title of professor and worked until the end of his life. A significant part of his folklore recordings — more than nine hundred handwritten pages of ballads, songs, legends, and proverbs — was actually rediscovered only in 2005 during the sorting of the archives of the Växjö City Library, which once again drew attention to the scale of his collecting work.

Swedish folklore began to be systematically recorded relatively late — in the 19th century, almost simultaneously with similar processes in Norway and Germany. The initiative of Gunnar Ulof Hylten-Cavallius played a key role in this. The first major publication in this field was the collection «Swedish Folk Tales and Adventures», prepared by Hylten-Cavallius in collaboration with George Stephens and published in 1844–1849.

The idea of their own collection arose in Hylten-Cavallius and Stephens shortly after their acquaintance in 1839 against the background of a pan-European interest in folk poetry. It is no coincidence that the publication was dedicated to Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm: their «Children's and Household Tales» were published in Germany as early as 1812–1814 and began to spread in Sweden in the 1820s in the form of cheap brochures. The Norwegian tales of Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, published in 1843, also became an important reference point. In the same year, Hylten-Cavallius and Stephens signed a contract with the publisher Abraham Bolin and began preparing the book.

Over several years, they managed to collect an extensive corpus of texts from different regions of the country. In the preface to the first edition, Hylten-Cavallius emphasized the principle of working with the material:

«We have systematized and reproduced the collected material without significant additions or changes. The only thing that belongs to us is some stylistic processing of the texts».

He also noted that the book is addressed primarily to the researcher but may also interest the «ordinary reader». In total, the collection included thirty-two tales, complete with detailed comments and regional variants.

The geography of the texts reflected the actual routes of the collectors. Seventeen tales came from Småland, Hylten-Cavallius's native region; seven from Uppland; two from Södermanland; the rest represented Värmland, Östergötland, Västmanland, Västergötland, Skåne, and Gotland. The collection did not have immediate commercial success, but individual tales became widely disseminated in the form of inexpensive reprints, and the work itself, according to Tishunina, «laid the foundation for a more serious scientific approach to the collection of tales and inspired many followers».

In 1875, an abridged version of «Swedish Folk Tales» was published, including thirteen texts and illustrated by the artist Egron Lundgren. It was this edition that formed the basis of the modern Russian translation. Thus, the result of the joint work of Hylten-Cavallius and Stephens was not only the first systematized corpus of Swedish tales recorded orally but also a model of publication that combined text fixation, commentary, and indication of regional origin.

«Troll, Be Satisfied with Yourself»

Despite different countries and historical contexts, many tales will seem familiar. For example, the collection includes stories similar to «Puss in Boots» or «The Frog Princess». But a significant part of Swedish folklore and the collection «Swedish Folk Tales» is associated with the images of trolls. The translator and Scandinavian expert Nataliya Budur calls them «the most famous character in Scandinavian folklore, primarily in tales and ballads». In the Swedish tradition, trolls appear not as isolated monsters but as a stable type of supernatural beings around whom recurring plot models are built — abductions, substitutions, trials, and the liberation of humans.

In folk representations, a troll is described as a large and repulsive creature: «he is big and ugly to look at», writes Budur, he may have one, three, nine, or even twelve heads, is distinguished by enormous strength, and at the same time is «terribly stupid», which makes him «very easy to deceive». The appearance of trolls varies: some are «as tall as mountains», others «no taller than a person», they have large noses with warts, wide mouths with fangs, small eyes, sometimes one eye in the middle of the forehead (which makes them resemble another mythical creature from ancient Greek mythology — the Cyclops), and grass or trees may grow on their heads. A constant feature is the tail, which in Scandinavian folklore generally serves as a sign of evil spirits.

The origin of trolls is associated with ancient mythology. According to Scandinavian legends, they descend from the jötnar — giants who inhabited the world before the appearance of humans. The word «troll» is considered very ancient and is found in all Germanic languages. According to Nataliya Budur, in the early «northern» languages, it denoted a mythological giant. In the pagan period, trolls were perceived as dangerous adversaries of humans, and after the Christianization of Scandinavia, they were seen as creatures associated with devilish forces. The sagas tell how they were fought by kings Olav Tryggvason and Saint Olav.

Over time, trolls move from myths and sagas into tales and ballads. Magical and chivalric ballads become especially widespread, where the plot is built around the abduction of a maiden, the substitution of a bride, or an enchanted groom. This plot is well reflected in the tales «The Golden Horse, the Moon Lamp, and the Maiden in the Troll's Cage», «The Shepherd Boy», and «The Three Dogs». Researchers note that from the 16th to the 19th century, such stories were among the most popular in Scandinavia. The boundary between the ballad and the tale remains blurred: in both genres, the hero inevitably encounters trolls or their relatives — elves and huldras (a mythical creature in the form of a girl with a cow's tail).

In the collection of Hylten-Cavallius and Stephens, trolls are presented in this folklore vein — as inhabitants of mountains and forests, abductors of people, and guardians of underground spaces. In Swedish and Norwegian tradition, it was believed that they lived in mountains and forests, sometimes alone, sometimes in families, and could occupy an entire mountain. They were attributed the ability to turn into animals or humans, abduct women and children, substitute «changelings», and keep captives in the mountains, forcing them to perform hard labour. At the same time, one could escape with the help of church bells, steel objects, or sunlight, which turned the troll into stone.

In the early 20th century, the image of the troll gradually moved beyond the oral tradition and folklore collections. In Sweden, from 1907 to 1937, the magazine «Among the Brownies and Trolls» was published, featuring texts by Elsa Beskow, Helene Nyblom, Anna Valenberg, and Jalmari Jaakkola. All of them, as Nataliya Budur notes, turned to troll themes. During the same period, the Swedish writer Selma Lagerlöf actively used folk tales: in the two-volume work «Trolls and Humans» (1915–1921) and in the novellas «The Legend of the Old Pasture» and «Halland Story», trolls act as harmful creatures, stealing livestock from people and abducting brides, thus preserving the functions assigned to them in traditional folklore.

The Swedish prose writer and playwright Jalmari Jaakkola also does not lose the negative meaning of trolls. Nataliya Budur writes that in his ironic tales, as in the works of the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen and Lagerlöf, trolls «embody evil and dark forces», and the formula of Ibsen's play character Peer Gynt «Troll, be satisfied with yourself» is used as a verbal designation of this principle. At the same time, the researcher retells the author's logic as follows: trolls exist within ourselves, and the tale works as a form of conversation about fears and evil without going beyond the сказочного образа (fairy tale image).

In modern children's literature, the image of the troll changes significantly. According to Nataliya Budur, trolls «have transformed from злобных и опасных противников человека (evil and dangerous adversaries of humans) into kind and cute little supernatural creatures», retaining hostility mainly in the fantasy genre. The most famous example is Tove Jansson's Moomin trolls: Moomin-troll, «similar to a hippopotamus with kind eyes and a tiny tail», lives with his family in Moomin Valley and «does not harm anyone». The connection with the folklore past is directly marked in the story «The Magic Winter», where the hero meets his ancestor — a «real troll».

In the latest Scandinavian publications, such as the books of Frida Ingulstad, the troll finally becomes the object of systematization: the reader is offered a complete set of rules and information — from origin to behaviour when encountering one. Against this background, the collection «Swedish Folk Tales» фиксирует (records) an earlier stage in which the troll has not yet been смягчён литературой (softened by literature) and remains a folklore creature with all its dangerous functions.

Publisher: Gorodets Publishing House

Translation from Swedish: Anastasia Tishunina

Number of pages: 192

Year: 2025

Age rating: 12+

Ekaterina Petrova is a literary reviewer for the internet newspaper «Real Time» and the host of the Telegram channel «Macaroon Buns».