Women's fiction: from pink covers to intellectual mainstream

How female writers took their place in the new literary reality

In the 90s, passionate covers with sexy golden-haired heroines and handsome men with bare torsos dominated the stores. And in the editorial offices, prose was born that could no longer be called “feminine” — too complex, too universal, too honest. At the discussion From Chicklit to Pulitzer on non/fictioN, they talked about how in Russia and beyond at the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st century, women began to write differently and became heard.

From Danielle Steel to Nina Sadur

In the 1990s, the women's novel was a genre with a recognizable face. Rosy cheeks, wind in her hair, a white shirt against the backdrop of a sunset and the name Danielle Steel. These images were imprinted on store shelves like a stamp, behind which it was difficult to discern other female writers. The moderator of the discussion and literary critic Natalia Lomykina said: “In the 1990s, when the newest literary history began to take shape, a women’s novel was more likely to be understood as a novel in a soft pink cover with a passionate handsome man and a golden-haired beauty. The absolute star of that time was Danielle Steel.”

Against this background, the emergence of Vagrius publishing house in 1992 turned out to be decisive. It became a platform for other women’s prose — serious, multi-layered, not intended for reading “on the beach.” Editor-in-chief of Alpina publishing house. Prose Tatyana Solovyova, who was starting to work at Vagrius at the time, recalled: “The beginning of the 1990s was a boom in book publishing, because suddenly censorship was abolished, everything became possible. Books were bought up immediately upon leaving the printing house. And this was a situation when everything poured onto the market.”

Daniela Steele was next to Sidney Sheldon, also a writer of women's novels, despite the fact that he was a man. But in parallel with this flow, texts appeared that did not fit into either the genre or expectations. Thus, Vagrius published the series Women's Handwriting. Not pink covers — black and white portraits, complex typography, and most importantly — completely different stories. “It was a revolution. Because there was no chick lit in this series. “Lyudmila Ulitskaya*, Dina Rubina, Lyudmila Petrushevskaya, Nina Sadur, Tatyana Tolstaya and so on came out there,” said Solovyova.

The very idea of the series came from the editors — it was a strategic move, an attempt to set the tone. Women received not only the right to write, but also institutional recognition. But how was that “female handwriting” defined?

“It was an attempt to go beyond the stereotype, the first systematic attempt as a publishing project. It was an attempt to give a panorama of the female writer's view of contemporary literature at that time,” explained Solovyova. The then young Olga Slavnikova also came out in Women's Handwriting. At the same time, Galina Shcherbakova was published — an example of traditional women's prose. And according to Solovyova, the differences between Slavnikova, Shcherbakova, Tokareva and Sadur were intuitively clear.

One of the turning points was the book “Kys” by Tatyana Tolstaya — a novel begun in the 1980s and published only in 2000. Nina Sadur wrote at the same time — with a focus on female characters, but without romance, without genre boundaries. Together they set a different vector.

Without gender

By the beginning of the 2000s, the publishing enthusiasm of the 1990s was replaced by another breath — scale. Women's prose ceased to be “small,” chamber, from the inside — it became epic. “In my opinion, then the heyday of family sagas began,” said Solovieva. The heroines of these novels were no longer hostages of the kitchen or a love story. They became participants in history. The events of the 20th century, tragedies, wars, emigration, family conflicts — all this became a framework in which women built their destinies. This is how the prose of Dina Rubina, Lyudmila Ulitskaya*, Maria Galina appeared.

It is interesting that similar processes took place in men's prose. “These are stories that were written by men, too. That is, this is the dawn of the great Russian novel," explained Solovieva. At that moment, women's and men's prose converged in scale and subject matter, rather than being separated. And this coincided with the last heyday of newspaper criticism. “Then there was still newspaper criticism, on which literature lived in the 1990s. But at the same time, a very powerful wave of new criticism appeared. This is criticism in glossy magazines. Number one in the 2000s was, of course, Lev Danilkin,” noted Tatyana Solovyova.

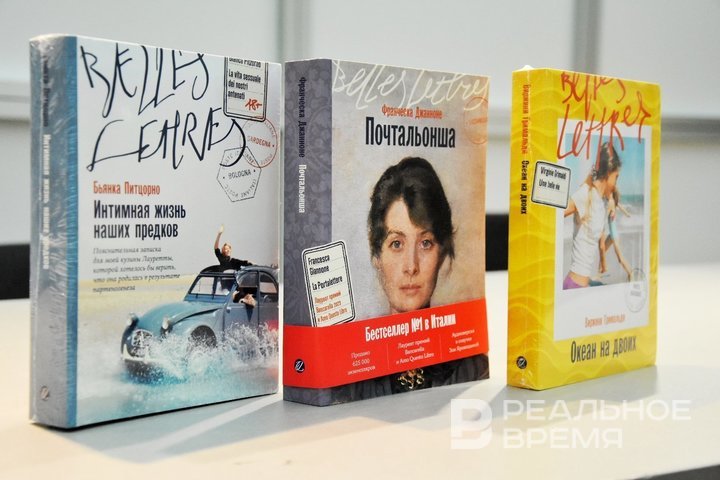

Against this backdrop, translated women's prose was actively entering Russia. And with it, new voices. Yana Gretsova, editor-in-chief of the publishing house Belle Letre, recalled that time as an era of pre-2000 jitters and a simultaneous literary boom: “The whole world was bewitched by Harry Potter, but at the same time there were quite a few other names.”

A breakthrough was Bridget Jones's Diary by Helen Fielding, a text that made feelings, uncertainty and loneliness a universal theme. “Our Russian reader suddenly learned that it was possible to talk about feelings,” said Gretsova. Others followed Fielding, including thanks to the popularity of the TV series Sex and the City.

But there were also those in translated literature who were difficult to fit into the genre. Donna Tartt with her novel The Secret History is a class of literature beyond gender. Anna Gavalda, Antonia Byatt, Elena Ferrante are names that have already become recognizable in Russia. “French fire, French love of life, art de vivre,” Gretsova outlined the main themes of foreign writers. If Russian women's prose was looking for a way to get out of the kitchen corner and onto the big stage, then translated prose brought models — how to speak differently, louder, without embarrassment.

By the 2010s, the boundaries between male and female prose had almost disappeared. But it was in the 1990s and 2000s that there was a dispute over language, over a look, over the right to be serious. This struggle — not only literary, but also institutional, publishing, editorial — changed the face of modern literature.

Strong, tired, lonely, silent, brilliant

She was an analyst for the Ministry of Internal Affairs, did not wear heels, did not want children and earned money with her mind. She did not want to be beautiful — she wanted to be needed. Kamenskaya, the heroine of Alexandra Marinina's novels, turned out to be the first mass heroine who emerged from the traditional female role. Not a lover, not a victim, not a saving mother. She was a heroine in the 1990s. But the “prose of 30-year-olds” is different. Tatyana Solovyova specified that the direct line from Marinina to today's heroines is not without its twists. Kamenskaya, revolutionary in the context of the 90s, quickly turned into a template.

“Yulia Shilova took Marinina's type of heroine, but only lowered her much lower. A kind of Russian Nikita, a love and adventure story, endless shootouts, chases and so on,” Solovyova noted. She compared the evolution of the heroine to the fashion industry. A trend shown on the catwalk appears in Zara and Gap a couple of months later, and after some time hangs in Old Navy. The same is true in literature: what began as a high assertion of female subjectivity turned into a narrative on the mass market.

The reader has also changed. Women's prose today is no longer a genre marker, but an alarm signal. “The first question from readers at fairs about women's prose: “Is it very dark?” Women's prose is already something heavy and dark," Solovyova shared. Because the heroine is no longer looking for a husband. She takes care of her mother with Alzheimer's disease, raises a disabled child, goes through an abusive relationship and lives with a sense of guilt that does not go away even in her sleep.

“Women's prose today is prose about domestic violence, about losses and experiences in difficult situations, about the loss of a loved one, it is a conversation about how your body fails you,” said Natalia Lomykina. These are no longer just texts — this is the literature of trauma. But at what point does pain turn into exploitation?

Gretsova drew a clear line: “It is very important for a book to give hope. But the direction that is absolutely not close to me is the detective as an admiration of the process of destruction, true crime, which, in my opinion, is now simply of inhuman interest.” She emphasized: evil should be called evil. Not romanticized, not stylized, not become aesthetics. This does not cancel the interest in complex topics, but changes the intonation. And here comes the point where genre literature meets great literature.

Solovyova defined the key difference: “Genre literature is built in such a way that the hero changes the world for the better due to his inner strength. And serious literature appears when even a strong hero demonstrates his weakness.” In these zones of instability, a new heroine appears — not idealized, not a superwoman, but subtly broken. A woman who has to be strong, but who sometimes simply cannot.

Literature for chicks and prose for consolation

And yet, a conversation about women's prose would be incomplete without genres that have been considered second-rate for decades. One of them is chick lit. Chick lit (from the English chick lit — literature for chicks) is a genre that emerged in the 1990s as ironic, light prose about young women, their career and love failures, shopping, friendship, depression and the calorie content of wine. The main icon was Helen Fielding's novel Bridget Jones's Diary.

But behind the gloss and lightness, according to Gretsova, an important task was hidden: “In any genre, you can create a magnificent work.” The claims to the genre are precisely in its simplification. When irony gives way to a template, and everyday drama turns into a mechanical formula. The same goes for another “light” genre — feelgood. Feelgood (English: feel-good — “to feel good”) is prose whose purpose is consolation. A genre in which even through grief and loss the reader comes to warmth to the finale. Gretsova treated it with respect: “Feelgood can be wonderful, magnificent. This is psychological prose. Then we say: topical prose, serious problems. And we have more and more such books.”

Problems of self-determination, choice, profession, social obligations, even political structures — all this can be told easily, but not superficially. And in this complexity lies the new face of women's prose. An example is the novel Time of the Butterflies by Halia Alvarez about the Dominican dictatorship of Trujillo. The theme is not feminine, the form is not “easy.” But it is written by a woman, and that is why the text gets an additional register. Because the female perspective is not a limitation, but a focal point.

And, perhaps, through pain, trauma, irony and genre tricks, this prose came to the Pulitzer Prize. Or, at least, to an honest conversation with the reader. Without glitter, but with depth.

*recognized as a foreign agent by the Russian Ministry of Justice

Ekaterina Petrova is a book reviewer for the online newspaper Realnoe Vremya and the author of Buns with Poppy Seeds Telegram channel.