The H-word: East Asian literature and culture through a different lens

At the Smena Summer Book Festival, Ad Marginem first announced the hide books project, which will publish books of East Asia and about it

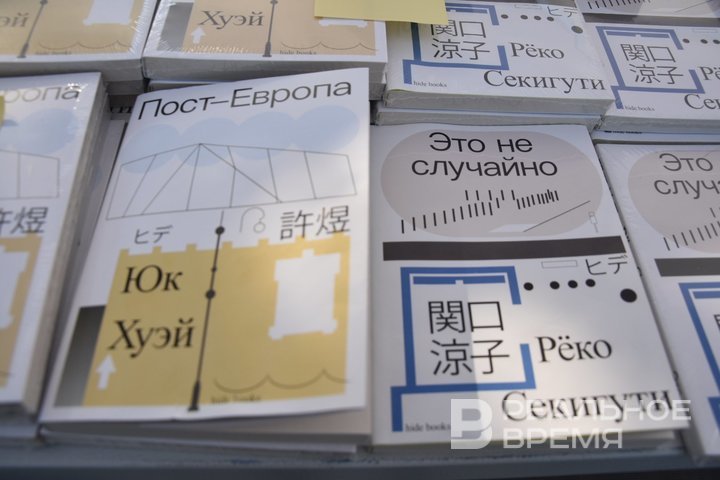

The first presentation of the hide books publishing project from Ad Marginem took place in Kazan, at the Smena Summer Book Festival. Among the first releases were a Soviet spy in Japan, a proletarian writer from Tokyo and a forgotten Japanese modernist. Increased interest in Asian culture brought a lot of new literature to the Russian book market — Japanese manga, Korean healing novels, and Chinese fantasy. At the same time, intellectual non-fiction, innovative prose, and essays from bright but unobvious authors have remained in the shadows. Founder of the project Mikhail Kotomin said that hide books will not “fill in the gaps.” Read about what exactly will be included in the portfolio of hide books in the report of Realnoe Vremya’s book reviewer Ekaterina Petrova.

Hidden dawn

The Moscow publishing house Ad Marginem has launched the hide books project, which the founders themselves call a “platform.” Director of the publishing house and initiator of the new project Mikhail Kotomin said at the presentation in Kazan that hide books works on the principle of an institution where people can come with their projects. For example, books are currently being published that were prepared jointly with two independent bookstores — Zhyolty Dvor from Saint Petersburg and Igra Slov from Vladivostok.

The main thing here is to agree on literary views. The publishing project is conceived for the publication of East Asian literature, which will show a different way of thinking and a different optics. “The publishing project was born out of interest in an alternative to the Western perception of the world, an alternative to Western modernism, which organized the culture of the 20th and 21st centuries,” said Mikhail Kotomin.

Geography and biography played a role in the birth of the project. Kotomin recalled Vladivostok, the city of his childhood. The city from where Seoul and Tokyo are closer than Moscow. Hide books essentially grew out of there. There, on the beaches of Primorye, Kotomin talked with Japanologist Valentin Matveenko. They tried to explain to themselves: why do you have to wait for a translation into English or European languages to read a Japanese poet? “Russia borders three large Asian cultures: Korea, China, and Japan. It is wrong that we need to resort to an intermediary language to find out what is happening literally under our noses,” said Kotomin.

This is how the hide books project was born, the name of which was not taken from a dictionary. The word hide does not exist in Japanese. But it suggests an image — and a direction. Hide is hi (sun) and de (exit). In Japanese grammar, they need to be connected with a link to get “sunrise” or “dawn” — hinode. But in hide books, the hieroglyphs are separated. They are read separately — and together. The result is “hide” — a neologism that suggests morning, charge, and hidden light. In English, hide is “to hide.”

The first book of the project is Post-Europe by Yuk Hui. A contemporary philosopher from Hong Kong, a student of Bernard Stiegler, and a professor at the University of Rotterdam, Hui does not try to hide the contradictions between the Chinese tradition and Western criticism. On the contrary, he writes from their very collision. “He constantly reflects on his Chinese tradition, so all his books are devoted to an attempt to answer the question of whether it is possible to combine the Eastern form of thought with Western questions,” Kotomin said.

Post-Europe is a text on the border of disciplines, worlds, and eras. Hui reflects on what a new kind of globalism could be, not based on unification, but absorbing the trajectories of Eastern thought. “The project of post-European development of the world has been discussed since the end of World War II,” Kotomin recalled. The term “Post-Europe” was first introduced by the phenomenologist Jan Patocka. Hui continues this line, but with a different emphasis: he is not afraid to walk along the edge of political relevance. And his text is an invitation to navigate in a world without dominant coordinates. Following Hui is a new book by Ryoko Sekiguchi. The writer has already been published in Ad Marginem, but “it is no coincidence” — Sekiguchi’s first book within hide books.

The third book was The Philosophy of the Tourist by Hiroki Azuma — a text about the gaze, movement, and position of the observer. Azuma, one of the greatest Japanese philosophers, understands tourism as a way of being in the modern world. His philosophy is a route. And finally, the fourth book is The Great Image Has No Form by François Jullien. A French sinologist, one of those who is returning Eastern codes to Western philosophy. The book is not just a study of Chinese thought, but an experiment in synthesis, an attempt to build an intellectual landscape where there is no centre, but there are points of proportionality.

An NKVD officer, a proletarian writer, and a forgotten modernist

Next in line for publication are three more books. They are interesting not only due to the content, but also personalities. For example, the book by the famous Soviet Korean Roman Kim. “He is considered the founder of the Soviet detective story. But we are interested in very specific journalism written by him at the turn of the 1920s and 1930s,” said Platon Zhukov, co-founder of the Yellow Yard bookstore. The discussion was about the collection of essays Three Houses Opposite, Two Neighboring Ones, and Other Texts — a book written at the intersection of cultures, ideologies, and intelligence missions.

Roman Kim was born in Korea, into an oppositionist family. His father sent him to Japan to learn from the enemy. There he lived in a Japanese samurai family, received a classical education, and then ended up in Vladivostok, where he joined the NKVD. Zhukov explained: “At that time, there was domestic Japanese studies, there were people who professionally studied the culture of Japan and China, and there was Roman Kim, who lived in Japan and knew it very well.”

But the most important thing is not the profession, but the conflict. As a Korean and as a Soviet person, Kim had complex feelings for militaristic Japan: disgust and passion. This, according to Zhukov, “slips through each of his texts”: “He burns with fire. He has a very sharp narrative style. It is interesting to read from a cultural point of view, because Kim says unexpected things that you are unlikely to learn anywhere else.”

Translator, specialist in Japanese studies and independent researcher Anna Slashcheva paid attention not only to the biography, but also to the language. “It was written in the strong formalist language of the 1920s, which, it seems to me, everyone loves now. Something in the spirit of Shklovsky, but even stronger,” said Slashcheva. Slashcheva became acquainted with this style when she accidentally found a PDF of the book on the Internet. This was about seven years ago. Someone “kindly scanned” the electronic version of the book and made it publicly available. Since then, her literary interest began. Slashcheva called the project “an attempt to unravel” Kim: “His biography is mysterious, there are a lot of blank spots, everything is classified, everything is unclear. And I want to try to see what sources he used when he wrote this book.”

The next project of hide books is Through New Siberia by Miyamoto Yuriko. This book is also being prepared by Anna Slashcheva. And again, it all started with a misunderstanding. “Miyamoto Yuriko is a proletarian writer. And, like all proletarian writers, I considered her a rather boring woman, but it turned out that everything was not so,” said Slascheva. Interest in Yuriko is being reconsidered today. But the main discovery is the figure of Miyamoto Yuriko herself, who in her maiden name was Chudzyo.

“In 1927, together with her friend, the Russianist Yuasa Yoshiko, they went to Russia,” said Slascheva. The girls spent several months in the Soviet Union — they were in Moscow and Leningrad. Then Yuriko went to London, but in 1930 she returned to Japan and married Miyamoto Kenji, the leader of the Communist Party. He insisted on changing her surname. “She wanted to continue writing under the pseudonym Chudzyo, under her maiden name, but he insisted,” added Anna.

The essay Through New Siberia is interesting not only for the change of names. Slascheva emphasized: “This is a look at the Soviet Union of the late 1920s.” Japanese leftist intellectuals of that time were fascinated by the USSR. Many traveled to Russia. Yuriko was one of the first. It is this Soviet trace, intersected with Japanese modernism, that makes the book significant for hide books.

The third book in the project line is Atolls by Nakajima Atsushi. Translator from Japanese and English Yekaterina Yudina spoke about it. Nakajima Atsushi is a Japanese prose writer, poet, and translator. For ten years, he taught language to high school girls and struggled with the burden of classical tradition — Japanese and Chinese. He was not published, and he did not believe in himself. “Woe from wit, Yekaterina Yudina said about him, explaining Nakajima's internal conflict. Everything changed abruptly: he became an official, went to the distant islands of Micronesia and suddenly realized that he was a writer. It was in this cultural “farsightedness”, in a view from the edge of the empire, that his best texts were born. In the short moment between self-awareness and death, he created several piercing, subtle works — like waves washing the shore at the border of land and water.

The collection Atolls is a rare case when Japanese literature goes beyond the borders of Japan and at the same time looks deeper into it. It is based on the impressions of Nakajima Atsushi from working in Micronesia, but, as Yekaterina Yudina said, “Nakajima, who does not write about Japan, writes about Japan.” These texts are a mirror that reflects the homeland through a foreign shore, a “position on the edge” that can highlight the secrets of time and space. Stories about the southern islands here turn into a fascinating, lively narrative, where, in addition to information, an “amazingly rare gift is important — the satisfaction of reading.” This is the most non-Japanese collection by a Japanese writer — and perhaps the most accurate.

Ekaterina Petrova is a book reviewer of Realnoe Vremya online newspaper and the author of Buns with Poppy Seeds Telegram channel.