Tatar-Japanese friendship: scientists and diplomats of the Land of Rising Sun speak about Kazan and its inhabitants

A famous expert in Eastern studies and columnist of Realnoe Vremya Larisa Usmanova tells about how the Tatars and the Japanese started to get acquainted with each other, what Kazan the Japanese envoy saw in the 19 th century.

One day in Kazan with the eye of a Japanese in the 19th century

The acquaintance of the Tatars with the Japanese and vice versa – the Japanese with the Tatars – started a long time ago. But deeper knowledge of each other was after Japan opened to the world.

Diary notes of travellers where authors tell about their impressions of representatives of another nation are one of the interesting sources of information. Many of such diary impressions could form stereotypes among the majority of the compatriots.

Probably Enomoto Takeaki, a Plenipotentiary Envoy of Japan to Russia and, consequently, the founder of the Japanese Navy, was the first Japanese to visit Kazan. He was the person who signed a convention with A. M. Gorchakov that solved territorial problems between the two countries in 1875.

Enomoto lived in Saint Petersburg for over 4 years from 1874 to 1878. He was held in high esteem and was a friend of representatives of the Russian intelligentsia. He was a strong supporter of the friendship of Russia and Japan. He decided to go home via Siberia in order to make sure that Russia did not threaten Japan. The Russian government permitted him to cross all the country and ordered local governments to help the Japanese traveller, provide him with security staff.

In his diaries, which have been found and published recently (in 2010) by a famous Japanese expert in Russian Studies Nakamura Yoshikazu, Enomoto writes in the second part headlined Voyage on Volga and Kama about a day spent in Kazan when he changed ships to go up to the Kama River to Perm.

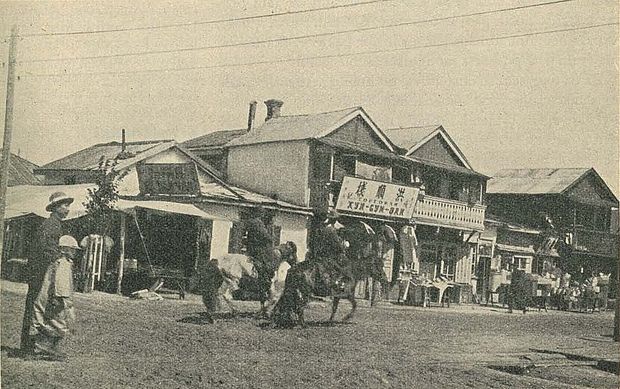

In July 1878, he started his trip across Russia together with two Japanese citizens – Ooka Kintaro who studied copper plate print in Japan and student Terami Kiichi. They arrived in Kazan on 31 July 1878 at 6 a.m. Together with Ooka San, he passed by a pyramidal monument – a monument to the people killed during the conquest of Kazan – till the next quay by carriage. One could get the centre of the city only on foot or by carriage. As they did not have the time to see the city, the Kremlin and just walk further along the street (because they needed to board a ship at 8 a.m.), they found another driver with a fast horse and approached the foot of the Kremlin. Enomoto notes the Kazan Kremlin's location is not as high as the situation of the Nizhny Novgorod Kremlin that he saw several days ago.

Enomoto and his fellow traveller got the main street of the city where he gave the driver 3 rubles for a fast trip. Enomoto notes there was access from the quay to the city by tram (probably, a horse-drawn tram).

He was surprised by the Tatars' blue eyes and hair of tea colour. He also noted the Tatars had big eyes and mouths, but they looked like Asian people. However, unlike the Asian people, they are much more beautiful, Enomoto writes. Their clothes look Persian. And men use a headdress. He also noted the Tatars are Muslim, and their writing system was based on the Arabic script. One Tatar man wrote him the Arabic alphabet when they were on the ship near Perm.

Enomoto writes that, unfortunately, he had to leave the city by 8 o'clock in the morning. At 12 o'clock, the ship with the Japanese travellers was on Kama and started to go up to the river. When they passed by Piyany Bor (today's Krasny Bor in Agryz District), a pine forest remembered Enomoto his motherland.

Enomoto spent more time in Sarapul. He bought good shoes for 5 rubles, which cost two times cheaper than in Saint Petersburg.

How a Japanese linguist learnt the Tatar

A famous Japanese linguist Hattori Shiro (1908.05.29–1995.01.29) also left his memories about the Tatars, not the Kazan Tatars but those who emigrated to Manchuria. The worldwide known Japanese linguist and honourable professor at the University of Tokyo who headed the Japanese Linguistic Community was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun in 1983 for his scientific work. The International Altaistics Community awarded him a gold medal for his achievements in linguistics in the same year. Hattori Shiro's endeavours comprise of four books 'Research of Altaic Languages. Selected Articles of Hattori Shiro' (Tokyo, 1986–1993).

He graduated from the Department of Linguistics of the Faculty of Philology from the Tokyo Imperial University. As a schoolboy, he was interested in the problem of the origin of the Japanese language that became the main topic of his scientific researches in his life. After his graduation, he went to Manchuria in 1933 in order to study the Ural-Altaic languages. A famous Tatar poet and emigrant Khusain Gabdyushev gave him Tatar classes in Harbin. Then when he lived in the house of a Tatar merchant Ageyev in Hailar, he met his future wife Magira. By the way, the Hattoris family led a big cultural and historical mission due to her. The most complete newspaper file of Tatar emigrants in Far East founded by Gayaz Iskhaki in 1935 that was printed till March 1945 was found in professor Hattori Shiro's archive.

Tatar wife of Hattori Shiro

His future wife Magira Ageyeva was born in 1912 in a village called Nagur in Penza Oblast. Her mother came from Tatar Yunik village in Tambov Oblast. In August 1916, the Ageyevs moved to Hailar and emigrated to Turkey after the Second World War. Having married Hattori Shiro in 1936, Magira moved to Tokyo where she passed away in 1999, later than her husband. He sister Asiya was also married to a Japanese. Having lived in Japan for several years, she got divorced and moved to her parents to Turkey. The son and two daughters of Magira Ageyeva and Hattori Shiro are alive and live in Tokyo.

If we imagine the difficulty of the situation at that moment and the attitude towards foreigners in very Japan, it is not difficult to guess that a marriage of a daughter of ordinary Tatar emigrant from Russia was a bold move for a prospective graduate from the Tokyo Imperial University. However, aside from sentimental reasons, there was an ideological one. The family of Mukhammedsha Ageyev was an active participant of the Tatar National Movement in emigration that Japan supported. An opinion about common roots of the Japanese and Turkic nations was spread in the academic and military environment. So the Japanese considered the Turkic people, in general, and the Russian Turkic emigrants in particular as kindred people to a certain degree.

Even if Magira had to move to the capital of Japan in 1936, she always kept in touch with her family and regularly received emigrant newspapers, including Milli Bayrak, which was a body of the Turkic-Tatar emigration in Far East, printed in Mukden from 1935 to 1945. Thanks to Professor Hattori and his wife, this unique source of information about the life of Turkic emigrants from Russian have survived almost completely. It was digitalised and is kept in the library of the Shimane University.

Hattori Shiro spoke several languages: Japanese, North Korean, Mongolian, Manchurian, Turkic (Tatar and probably Turkish), Chinese, English and Russian as well as Ainu and Okinawan. He thought a personal communication with a speaker is one of the key methods of learning a language. As a scientist, it allowed him to get a deeper understanding of pronunciation in Japanese. He was the first person to confirm the similarity of the Japanese and Okinawan languages. He also found out the origin of the Old Mongolian language. He did a detailed research of the language and script of 'The Secret History of the Mongols'. It was the topic of his doctoral thesis in Philology that he defended at the Tokyo Imperial University in 1943.

In 2003, after the death of Hattori Shiro and his wife, the archive of the scientist was given to the Shimane University. Separate original editions of Milli Bayrak newspaper and other materials issued by the Turkic emigration like schoolbooks are kept in the Ural-Altaic Language Archive. A thesis on Turkic-Tatar emigration to the Northeast Asia based on the materials of the scientist's archive was presented in 2006. In 2014, the first seminar dedicated to the life and work of the Japanese scientist and expert in Turkic Studies took place in Kazan and Moscow. And due to an academic exchange agreement between the Institute for North East Asian Research of the Shimane University and Sh. Mardjani Institute of History of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tatarstan, the project on digitalisation of Milli Bayrak newspaper was carried out. And its copy was given to the scientists of the Republic of Tatarstan.

We see a mutual attraction of the representatives of the two nations. The Tatars have a keen interest in the Japanese experience in the modernisation of the society. The Japanese show their obvious interest in ethnical peculiarities and the Tatar experience in passionarism, which was demonstrated in the 19th-20thcenturies.