Tatars in Japan: dwindling diaspora and ‘Tatar’ metal for samurai swords

The researcher of Institute of History named after Mardzhani of RT Academy of Sciences Marat Gibatdinov in conversation with the correspondent of Realnoe Vremya told about how the scientists from Tatarstan have discovered for themselves the Land of the Rising Sun. From here they brought to Kazan the first printed in Japan Koran, here they learnt that the steel for the famous samurai swords are made according to 'Tatar' technology.

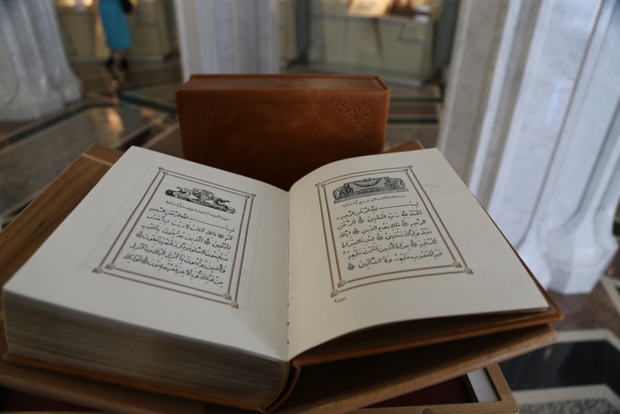

On international day of monuments protection, the collection of the Museum of Islamic culture has been added with a valuable exhibit — the first printed in Japan Koran. The descendants of the famous Apanaevs clan gave it to Kazan historians. The head of the Center for history and theory of national education of the Institute of History of Tatarstan Academy of Sciences Marat Gibatdinov told about how our researchers managed to get in touch with the Tatar community in Japan, how many trips to Japan it took in order to establish contacts with them, and also about the future plans of the group of Kazan historians.

Nameless books from the archives of Hattori Siro and unusual Koran

Marat Mingalievich, could you tell us when you became interested in the topic of Tatar immigrants in Japan?

The impetus was given by our meeting with Larisa Usmanova (senior fellow of the Institute of History of AS RT, associate Professor of the Russian State University for Humanities), she lived a long time in Japan, studied there, defended, wrote a thesis in Japan. In general, she is a serious specialist. A few years ago we just met at a conference, got to talking and expressed wishes that it would be good to do these problems. And so it happened, apparently, stars aligned, or something, so we could just after some time to organize joint projects.

How many times have you visited Japan in the framework of your research? As I understand, the trip from which you brought the Koran was not the first?

The trip to Japan, from which we brought the Koran, was not the first. Just this time there were Days of Tatar culture and, due to that, our President supported this idea, we were able to spend these days, to hold an international conference called 'Cultural-economic and technological ties of Japan and the Tatar world'. In the framework of these activities, last autumn we had meetings with representatives of the Tatar community, representatives of the older generation of emigrants.

In total, we had three trips to Japan. First, if I am not mistaken, took place in 2014, then last year there were two trips… Some of them were connected with the international conferences held in Japan, some were organized in the framework of our research projects. In general, we have two areas of work with Japan.

'The trip to Japan, from which we brought the Koran, was not the first...' Photo: kazan-kremlin.ru

First, it is our research project 'Tatar documents in foreign archives', where we try to study those materials that are stored in universities, some private funds and we are trying to preserve or, perhaps, return them to Tatarstan. Another direction is the scientific cooperation with our Japanese colleagues at the Shimane University, where the archive of Japanese turkologist Hattori Siro is stored. He was married to a Tatar woman — Magira Ageyeva. In that archive, which they handed to the University, there is a large number of books that were published by the Tatars during the time of emigration from Manchuria, and then from Japan.

Our trips were connected with the study of these materials — with what we have started. When we invited a Japanese colleague who studied this archive, there was a very interesting picture: their researchers knew that these books are Tatar, because at the back of some them there was annotation written in Tatar, but they could not read it, and they simply called them: 'book A', 'book B' and so on. And he started in the presentation to show the covers of these books, the scientists who were sitting in the audience, began to read in chorus the titles of books — because for us it was no problem to do that, it was written in Arabic script, but in Tatar language. In our first trip we looked the Tatar part of this archive, made a catalog, and we hope to publish this catalog of the archive of Hattori Siro this year.

If to remember Koran, which you donated to the Museum in April, why is this exhibit interesting?

It would seem, that it has long been known that the first Koran was published in Japan due to the activities of the Tatar community, in the printing house, which the Tatar-Muslim community founded in Tokyo in 1934. It was generally accepted because there were publications in press at that time, there are photo of activities that were arranged that time. And it was known that this Koran was presented to the Imperial family. But when we got the instance, it was found that there are so many questions: first of all, it turned out that it was based on the so-called Kazan Koran published in 1913, this fact was previously unknown.

Besides, it was found that at the end of the Koran, that is not quite usual, there is the final article of Imam Muhammad Kurbangaliev, where he describes general rules for storage of the Koran. In addition to purely theological questions, this article describes how this Koran was created, which communities and how much money allocated, and there is the date — 1938. Now we are trying to figure out the reason for such differences, because on the cover and on the case there is a number – 1934, but on the Japanese annotation and the article of Kurbangaliev — 1938.

Now we are trying to figure out if it is reprint, or… Due to the materials, which we also found during our first trip, in the family archives of the son of one of the imams of Tokyo mosque, we found the photos of the presentation ceremony of this Koran, which was held in the 1930s, and when we began to study this photo, it turned out that in the background you can very clearly see these Korans, perhaps, there were two editions of these Korans that differed in format.

'It was based on the so-called Kazan Koran published in 1913'. Photo: kazan-kremlin.ru

Dwindling Tatar diaspora and the help from the famous Apanaevs clan

How large is Tatar community in Japan?

Unfortunately, now it is not so large, because it was originally small. The Japanese, in general, gave an opportunity to emigrate to Sweden only to the elite, and in order to obtain such permit, they had to provide certain financial guarantees — only wealthy people could qualify for refugee status. Besides, even after receiving this status, they could not apply for citizenship at that time, and it, in general, greatly limited the possibility of movement outside of Japan, because they had neither the Soviet nor Japanese passports. And when in the 1970s the Turkish Republic decided to give the Tatar immigrants an opportunity to obtain Turkish citizenship, many of them took advantage of it and left — somebody in Turkey, somebody in America.

Now, in general, very small number of Tatars have left from that old emigration in Japan and they are all in very old age. There is also a new immigration, new immigrants who found work, who are studying in Japan, but this is a completely different community, but they are also not so many.

An impressive part of the archival material you have found at the Apanaevs. Could you tell us more about this family?

The Apanaevs is interesting for many reasons. First, it is one of the branches of those Apanaevs — famous merchants of Kazan. We have the Apanaevskaya mosque and a large number of houses, which are still preserved in Kazan. They were large merchants, patrons. It was a family, who made a great contribution to the development of the Tatar people in different aspects — in financial, cultural and so on.

'Now there is very small number of Tatars from that old emigration in Japan.' Photo: татаровед.рф

The successors of the dynasty in Japan, they were also actively involved in the life of the Tatar community. Suffice it to say that the father of Apanaevs, who acquired this Koran that we have donated to the Museum of Islamic culture, he was not only personally acquainted with Ayaz İshaki but was his employee for some time, he also played quite an important role in the Tatar community in Japan.

His children, who gave us this Koran, they were businessmen, occupied very important positions. They were one of the founders of the prestigious business club in Tokyo. One of the brothers for a long time occupied the position of top manager of the international class, headed the airport in Tokyo, then headed one of the most important and largest airports in Europe, which is located in the Netherlands. They, like many representatives of the Tatar community, occupied relatively high positions, could find their place in this new environment and preserve all heritage that has been handed down from ancestors. Today, thanks to them, we can touch the heritage of those Tatars who lived in Japan in the early XX century.

We were very pleased and surprised when it turned out that the Apanaevs stored binders of newspaper 'Milli Bairak', which we have been looking for and just those editions that we lacked. They said they are ready to provide these editions to copy, and in the future they are ready to give it to Tatarstan as a legacy. During that meeting we were also shown the Koran, and they expressed a desire to pass it on to Kazan. And we promised that on return we will give it for safekeeping to the Museum of Islamic culture, and so we did.

'Tatar metal' for samurai swords

Could you tell us about the most interesting findings in the framework of your research?

In the course of our work there was raised the topic of production technology of steel, which the Japanese call 'tatara'. They have always known and, in general, still recognize that this technology came to them from Asia, but it is unknown from which part. There is a suggestion that this technology came to Japan from the ancient Tatars from the territory of the Altai Republic. Altai is not only the ancestral home of the Turkic peoples, but also one of the centers of metal industry. This technology is today a national treasure of Japan, as the famous samurai swords, which the Japanese are proud of, can be made of steel, which is made by the technology 'tatara'. And the Japanese side is very interested in the study of the history of this technology, and from our side there is great interest too. Now we are trying to develop this direction. We started with a small archival project, but it turned out that we have a lot contact points with Japanese colleagues.

'Famous samurai swords, which the Japanese are proud of, can be made of steel, which is made by the technology 'tatara'. Photo: heikido.ru

And what about the most important finds?

The most significant find, well, my personal one, is missing copies of the binder of the newspaper 'Milli Bairak'. So that readers could understand what the importance of this find: the paper was published in Manchuria in the 1930-194s, and the creator was Ayaz İshaki – he is an iconic figure for Tatars. The peculiarity was that, as it turned out, this newspaper has not been preserved anywhere in the world in full. The most complete filing was discovered just by Larisa Usmanova at the Shimane University and now, thanks to the collaboration with the University, we managed to make high quality scans of the editions and to bring them to Kazan in our Institute. The rest of them we couldn't find.

Some editions were in Kazan, which were given by Tatar emigrants. We wanted to look in the library of Congress, or in the London library. But it turned out that those missing editions of the newspaper are stored in Tokyo near the mosque where we have been.

Last autumn, when the Apanaevs invited us, they showed us these binders, and it was really such an unexpected and joyful event. Besides, it was found that the binders that the Apanaevs store, they are in very good condition, even better than those stored in the Shimane University. For me it was a very significant event, because now we can finally piece together a complete newspaper file, and it will be such a unique collection, which will allow us to study the life of the Tatar emigration in the 1930-1940s in the Far East. This is a very valuable source.

The life of the Tatar emigrants was very rich — they had their own schools, their publishing houses, they published their books, we were also found them in Shimane. It was very touching when we found collections of Tuqay in this archive, which were published in Manchuria, the books of Tatar language or grammar of the 1930-1940s. There was another interesting find — a movable alphabet for children. All this suggests that emigrants lived a very rich cultural life.

In conclusion, could you tell us about your future plans: perhaps, you are planning another trip to Japan or, conversely, you will host the Japanese side?

Unfortunately, due to this crisis, we are not planning any trips to Japan, but thanks to our cooperation, in August, we expect a large delegation of Japanese scientists who will arrive in Kazan. Here we have a big conference.

Perhaps, in August, a theatre group will come that will show a traditional representation called kagura. It is a perfomance, which is based on Japanese myths and originally was staged in the temples. For us, this kagura is very interesting, because one of the major myths is the myth of the struggle of a hero with a dragon, which resonates with our mythology — with Zilant and so on.