In Doha to the bitter end: why negotiations of oil cartels were doomed from the start

Oil cartels, expressing extreme displeasure and trying to intimidate by promising to raise oil prices again, are becoming an obsolete institute. The economic columnist of online newspaper Realnoe Vremya Albert Bikbov is puzzled – why did they gather? Since the technological advances in oil production have beaten the policy of cartel agreements. But, apparently, not everyone understands this.

The sheep and the goats

Oil prices fell on Monday after the failed meeting in Doha, at which the largest countries-producers of OPEC and states outside the cartel failed to reach an agreement to freeze the oil production, undermining the credibility of the cartel and not solving the problem of oversupply in world markets. Futures contracts on Brent oil fell by nearly 7% at the beginning of trade on Monday, and by 3.30 pm MSK recovered to $41.36 a barrel, but still traded below the last closing more than 4%.

Imagine the following metaphor in order to understand the whole comicality of such negotiations.

Imagine there is a fictional house. The initiative group of residents of one of the houses decided to change the old broken door with a new iron one. They inform all about the meeting, but a part of the residents do not attend it deliberately. Anyway, the meeting starts, the remaining residents tedious are trying to keep the record and establish an agreement on the need to install a new door and how much money to collect from each. The resident Sidorov, present at the meeting, has only one thought: 'Ivanov has ignored the meeting, but I will be ripped off money for the installation of a door and Ivanov will use it for free, because it is impossible not to give him the keys — he has the rights, and he opposes the installation of a new door. No, I will not pay — let other fools pay!'. Petrov is standing next to Sidorov and thinking: 'Well, it is clear with Ivanov, he is a known scumbag, he will not pay. But Sidorov… Sidorov is cunning, he knows that Ivanov will not pay, and he also will not pay. And I will have to pay for bothof them. It will not work out — I won't pay, let other fools pay'. And few residents who came to the meeting will have these thoughts. As a result, there is no a new iron door and it will never be.

In other words, this is a classic problem of any collective action — 'the stowaway problem'. In a group, there are always 'goats', those who wish to ride at the expense of others. If you have nothing to influence on 'goats', 'sheep' will succeed nothing.

The Doha negotiations were doomed to failure — the most important part of the participants did not come intentionally. On Sunday, the meeting in Doha was attended by 18 countries, including 11 countries-exporters from the organization of oil exporters (OPEC) and 7 countries outside OPEC. These 18 countries account for about half of the world's oil production and more than 70% of global oil exports.

But the USA and Iran didn't come.

It is clear with America: they have always flatly refused to participate in any price 'arrangement'. But their participation would be very important — as a result of the American 'shale gas revolution' the global energy landscape has greatly changed – the US started to rule the roost, in 2014 for the first time since the 1970s they surpassed Russia and Saudi Arabia in oil production.

With Iran, it is also clear: they refused to freeze its extraction from the very beginning. The representatives of the Islamic Republic, which only in January 2016 returned to the world market after the lifting of international sanctions, stated that they are not going to restrain the extraction until it reaches the level before sanctions (4 million barrels per day). According to March statistics of the OPEC, the daily production of Iran amounted to 3.29 million barrels.

The old birth trauma

The culprit of the breakdown of talks is considered to be Saudi Arabia — OPEC's largest producer demanded to review the draft agreement. The first option, which the journalists managed to read on Saturday, on 16 April, was quite clear: the freezing of the production until 1 October at the level of January 2016, the creation of the oversight committee, a new meeting in Russia in October 2016. But Saudi Arabia demanded that all OPEC countries adhered to the agreement, including Iran, which had already refused to do it. In the end, there's no agreement: the Ministers from 18 countries — 11 of 13 members of OPEC (except for Iran and Libya), as well as Russia, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Colombia, Mexico and Oman departed from Doha with nothing.

But we shouldn't blame Saudi Arabia — they quite rightly raised the issue on Iran's participation in the agreement. The Saudis decided that in conditions of excess supply from uncontrollable American suppliers we need to fight not for the prices but for the volumes, protecting their traditional markets and trying to attract new customers, even by blatant dumping.

Besides, their old birth trauma started to ache — once the Saudis already tried to reduce the production drastically — all was to no avail. In the period of quote decline between 1981 and 1986 (the fall in oil prices of the same scope), the Kingdom tried almost single-handedly to pull the world out of the price abyss and reduced production to a record low – from 10.3 million to 3.6 million barrels per day. The result for Saudi Arabia was very disappointing. The policy did not affect the price of a barrel — the market plunged into a prolonged period of cheap oil. However, for the experiments with the limitation of the production they had to pay a lot: the level of income per capita dropped significantly. Only in twenty years Saudi Arabia reached the former levels of oil production, and it has not fully restored its share in the market yet.

Saudi Arabia did not want to fall into the same trap for the second time — there they have finally understood that the withdrawal of any suppliers from the market through voluntary or involuntary freezing of extraction will mean the only thing: the USA will quickly take the vacant niche. Uncoordinated market actions of oil companies in the USA have defeated the schemers from the formerly omnipotent OPEC. Technological progress has beaten the policy.

Marginal costs as a margin safety in the price wars

In order to understand the reasoning of the leading exporters, it is necessary to refer to the concept of a 'marginal cost'. Marginal costs — additional costs for the extraction for each extra barrel of oil. Making a decision to increase or to reduce production, they take in the calculation the marginal, not average (prevailing over a long period), costs. All are interested in the marginal costs 'here and now' and not averaged with good prosperous periods.

It is clear that one who reduces or simply does not increase oil production, he loses not only income but also the market. Rational behavior is to increase production if the costs allow. Marginal costs in different countries are different. And it not only shows the margin of safety of one or another country in a price war but also provides a completely different motivation and immunity to various kinds of price cartel agreements.

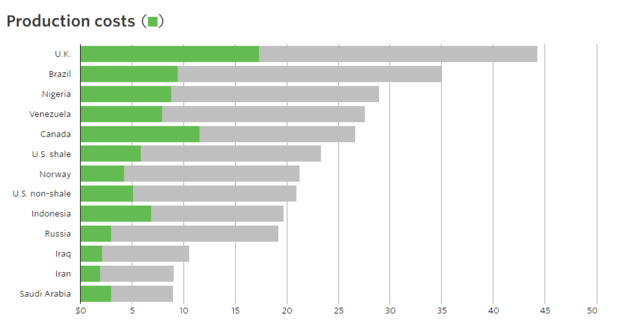

Take a look at a very clear visual reference.

Margin costs in the total cost of extracted oil in the countries based on data from April 2016

In the diagram, the green is the marginal (production) costs for each additional barrel of produced oil by country. Grey — the total cost of production. As you can see, Iran and Iraq have very low marginal costs — about $2 a barrel. Saudi Arabia and Russia a little more — about $3 a barrel. By the way, Tatneft also has a low marginal cost of oil production at developed fields: in the third quarter of 2015, the expenditures on oil production averaged 279.0 rubles per barrel, or about $4.5 per barrel (Rosneft, by the way, has around $3.0 per barrel). The U.S. — about $5-6 per barrel. Canada, Britain, Brasilia and Venezuela are in the worst position.

It is not surprising that the low marginal costs were the main motivating factor for Iran and Saudi Arabia for the breakdown of negotiations. You can ask the question: 'Why does Russia want to reduce the production if it has low expenditures?'. The answer to this question is rather simple: marginal costs when increasing or even maintaining the production level tend to increase, as oil is an exhaustible resource in the short-term prospect. Each barrel is given harder and harder. And here the crucial thing is the ease of extraction of these new barrels: it is clear that the Persian Gulf countries it is much higher than ours. That is, the marginal costs of the Russian producers will grow much more rapidly than of the countries of the Persian Gulf, and even faster than of the Americans, who can easily increase the volume of production amid the growth in oil prices above $40-50. So, the motivation of Russia is clear: we want the cartels do exist because we can't increase production with reasonable costs. But, as Doha showed, the oil market has received an important signal: each country speaks for itself, again. And no cartels!