''Contemporary Russian literature seems to me narcissistic and simply uninteresting''

Editor-in-chief of Phantom Press publishing house about the publishing market, ''great Russian literature'' and contemporary censorship

Phantom Press is a small publishing house with a history. Without investors, relying on its own taste and a loyal audience, it started with foreign detective stories in the 1990s, while now it's publishing Stephen Fry, Jonathan Coe and Khaled Hosseini. For Russia, for which market monopolisation is a common thing unlike Europe, this company's experience is quite interesting. Editor-in-chief of Phantom Press Igor Alyukov told Realnoe Vremya how the publishing house is fighting off competition.

''One book a year that settled in stock isn't a catastrophe, two – is already unpleasant, and three – is a grave miscalculation''

Igor, how did it happen that Phantom Press occupied quite a specific niche in the publishing world, that's to say, publication of foreign literature?

Phantom started with foreign literature in the early 1990s, the turn to non-genre literature in the late 90s. We have dealt with precisely foreign authors from the very beginning, we've gained authority over time – among readers and book journalists, authors and literary agents. I think this is to a great extent explained by personal interests too, as the publishing house is very personalised, it's the director and the editor-in-chief's tastes, predilection and interests that define the publishing policy and the content of the portfolio. But some time ago we had a desire, which wasn't that strong, to expand our geography with Russian authors as well. And this will happen in 2019.

How did the publishing market look in Russia 26 years ago when the publishing house had been just created?

How any market in Russia did. Spontaneity, being apart from the world market, it had nothing to do with law – publication of pirated editions was on the production line. By the way, we've published books legally from the very beginning: the publishing house's history began with signing a contract with Joanna Chmielewska.

How did your publishing house manage to save its independence, while it's small and you don't have investors?

We wonder ourselves at times. Undoubtedly, we had tough years. But now, when the majority of small publishing houses either stopped existing or have been absorbed, we feel quite confident. The publishing house's compactness is probably one of the reasons, we don't have a PR department, sales department, HR and security.

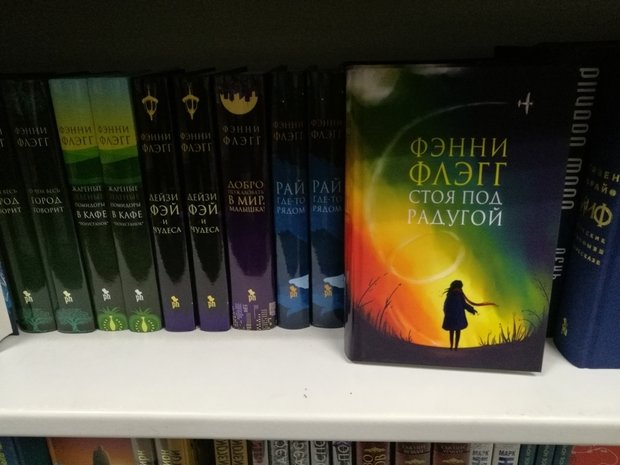

''Relations with authors are also important for stability. Lasting years of cooperation link us with some. For instance, we've been publishers of Stephen Fray, Jonathan Coe for almost 20 years already and a bit less of Khaled Hosseini.'' Photo: picgra.com

A scrupulous approach to the replenishment of the portfolio of publications is another, perhaps more important reason. We understand we can't make a mistake, that one book a year that settled in stock isn't a catastrophe, two – is already unpleasant, while three – is a grave miscalculation. Big publishing houses or publishing houses with capital behind can't afford it, we can't, and we need to hit the target, and we learnt how to do it quite a while ago. The publishing house has its own audience that is purposefully interested and waits for our new books, and it's quite big.

Relations with authors are also important for stability. Lasting years of cooperation link us with some. For instance, we've been publishing Stephen Fray, Jonathan Coe for almost 20 years already and a bit less – Fannie Flagg, Khaled Hosseini. More powerful publishing houses began to poach some authors whose books became quite the bestsellers in Russia but were denied.

''The combination of literary level and thrill is important''

What interesting books are you publishing now?

Talking about what has been just recently published, it's a milestone for me – Richard Russo and Eki Kurniawana's novels. Russo is a maestro of American literature that hasn't almost been translated into Russia illegally. We wanted to publish him as early as the 2000s, but it was always postponed. But it happened late last year – we started with a Pulitzer Prize winner Empire Falls translated by Yelena Poletskaya. I'd say it's a perfect Phantom novel – a combination of literary level and thrill.

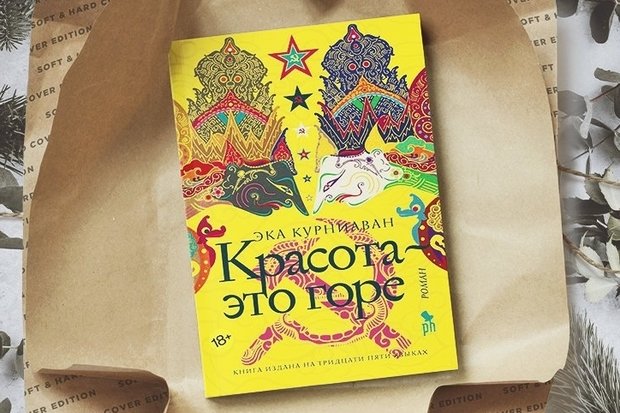

Another joy of mine is Indonesian Kurniawana's novel Beauty is a Wound translated by Marina Izvekova, it's not a book but joy, almost crazy synthesis of history, magic realism, Shakespeare's drama and comedy. We don't forget about detective stories, which our story began with: we started to publish Tana French, a top-class Irish writer of detective stories. Late last year, we published one of her latest novels The Secret Place translated by Maria Aleksandrova and Gleb Aleksandrov, we will continue this year. The latest novel of one of our favourite authors and a friend of the publishing house, Jonathan Coe, Middle England translated by Shasha Martynova has just been published.

''Another joy of mine is Indonesian Kurniawana's novel Beauty is a Wound translated by Marina Izvekova, it's not a book but joy, almost crazy synthesis of history, magic realism, Shakespeare's drama and comedy.'' Photo:picgra.com

How do you choose books you will translate and publish?

Phantom's publishing policy has transformed over years, but the principles have remained unchanged. Firstly, a book must be interesting for ourselves (director of the publishing house Alla Steinman and me) as readers. And if one of us has strong objections – and ''I don't like'' is probably the most important thing – this book won't be in our portfolio.

Secondly, that combination of literary level and thrill, which can have different types, is important for us. Even if we publish a book for commercial success (because we need to stay afloat), the key condition is we shouldn't feel shame for it. And as we've been applying quite a personal approach when choosing books, we have a big number of debutants or authors who are completely unknown in Russia or authors with exotic names who scare other publishers. However, we don't rush to buy the rights to books with a resounding international success if we don't like them.

''We live in the conditions of total digital piracy, the absence of normal book selling network and book infrastructure''

What's the difference between the work of European and Russian publishing houses? How do their and our market work?

It's quite a complicated question. On the one hand, the principles are similar. On the other hand, there are many nuances in Russia. I've never worked in a big publishing house, this is why I don't dare to say how it works. As for small publishing houses who don't have a conveyor but personal approach to publishing but aren't fully handmade in general, I think we are almost similar to our British, French or Spanish colleagues. Except one thing, they work in much more comfortable conditions.

The specifics of the Russian market, besides its fluctuation due to the political situation and other reasons, is that we live in the conditions of total digital piracy, the absence of normal book selling network and book infrastructure in general, from the same book selling to a microscopic number of editions and people who tell about books.

Does the state somehow participate in publishing in Russia?

It's quite a funny question. In my opinion, microscopic. No, of course, there is a kind of institute awarding grants, which probably look like sops. That's it in fact. The only help of the state, in fact, comes to a concessional VAT rate for publishing and book selling. But it's neutralised by other factors.

''The specifics of the Russian market, besides its fluctuation due to the political situation and other reasons, is that we live in the conditions of total digital piracy, the absence of normal book selling network and book infrastructure in general.'' Photo: Maksim Platonov

''Contemporary Russian literature seems to me secondary, quite narcissistic, simply uninteresting''

How do you assess the state of contemporary Russian literature? Can you name the authors and compositions that truly surprised you?

I'm bad at contemporary Russian literature. It seems to me secondary, quite narcissistic, simply uninteresting. I unwillingly always compare with English texts, and, sadly, in my opinion, a Russian author's book almost always loses. Perhaps I'm biased, but I've very rarely seen something Russian that seriously interested me.

I have quite specific complaints about Russian authors: a lack of skills to work with plots (often disguised as disdain), fixation on the style and literary adornment (we fail to overcome it) and, most importantly, fixation on ourselves in different ways. I prefer when an author tells me a story, not shows himself off.

As it seems to me – here it's important that it's just my opinion – that a contemporary writer in Russia still writes ''for eternity'' I think, trying to unconsciously climb up onto the train of great Russian literature that left a long time ago. It's an obvious road to nowhere. And a Russian writer should carry out a revolution inside.

But sitting in a plane to Krasnoyarsk several months ago, I opened a file with a novel we were offered to publish. And I didn't close it until we landed. As a result, the list of our authors has had a Russian name. We will publish Anna Kozlova's novel in the spring, which will be called Rurik, and it's an excellent book. And it's not advertising. I began to read with great scepticism, very biased, but the novel turned out charming, and it's the case when an author tells a story and remains in the shadow.

Is there demand for literature in our country? If so, what literature and from whom?

The number of readers in the country has reduced, of course. We aren't the most reading country in the world (neither have we been, of course). But the remaining circle of readers has a very good quality and is firm with its predilection for the book. Undoubtedly, it has requests, and, in my opinion, they are quite diverse. I don't dare to judge how much all kinds of trash novels, detective stories and accidental travel books are demanded and by whom, this doesn't have a direct association with literature. As for normal literature, including mainstream, the range of predilection, tastes is very wide, and this is why our book world is quite diverse.

''The number of readers in the country has reduced, of course. We aren't the most reading country in the world (neither have we been, of course). But the remaining circle of readers has a very good quality and is firm with its predilection for the book. Undoubtedly, it has requests, and, in my opinion, they are quite diverse.'' Photo: facebook.com/igor.alyukov

''Books of foreign authors where Russia is featured is probably the only thing that Russian readers (and publishers) don't like''

Is there censorship (direct and indirect) of foreign books in Russia? How does it look? What do you think about age rating of books?

Direct censorship touches, first of all, books designed for children and teenagers. Here, as I understand, everything is quite strict. All is simpler for books for ''adults''. We adapted to the ugly requirements, this is why we always indicate the age: we place 16+ to a book that a fifth grader could read without being afraid for our moral appearance, and there is at least a hint it's not for ''children'', we place 18+ and pack the book into a film.

Unpleasant stories happen at times too – pseudo-readers' claims. For instance, a reader in a town not far from Moscow sued against a bookshop for propagating fascism in John Boyne's book The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, a purely anti-fascist novel. And late last year the LDPR and Vladimir Zhirinovsky brought a legal action against us for mentions in Charles Clover's political book Black Wind, White Snow. Of course, choosing books, we need to keep Russian specifics in mind, but it's not the most important thing for us. At the moment.

What distinctive themes raised in foreign literature are also topical in Russia? Is there any delay?

We're completely unique here (despite our own national opinion): the Russian reader is concerned and interested in the same themes the European and American ones are. An injury, recovery; the military theme; reconsideration of the 20 th-century history; feminism and post-feminism. I wouldn't unify readers, they are very diverse. This is why almost any theme can be interesting for somebody. Books of foreign authors where Russia is featured is probably the only thing that Russian readers (and publishers) don't like. And we don't reproach the reader or the publisher here but the authors – sadly, the amount of nonsense continues oppressing.

In one of the interviews you said: ''Book exhibitions are a good illustration of the contemporary reader.'' What's happening there now? Are new types of readers appearing?

I don't know what about a new type, but new readers are certainly appearing. I'd say that now there is a new, young wave of readers, which inspires. And we learn of it on exhibitions. The audience on our stands have seriously changed in the last years: it has become younger, became… more inspired. And many of the new readers are directly connected with social networks – quite specific communities based on interested are really appearing there.