Tatars in Europe: pre-revolutionary dreams about Sorbonne, transfer of technologies and French governesses

Review of historical ties of Tatars and Western Europe in the 19th – early 20th centuries

President of Tatarstan Rustam Minnikhanov visited Paris last week. However, Tatars turned their eyes towards France and other European countries as early as the 19 th-20th centuries. Kazan historian and columnist Realnoe Vremya Liliya Gabdrafikova dedicated her column to this phenomenon.

To the West – for goods and technologies

We wrote that the European culture reached a majority of Tatars in an adapted version through Istanbul in the late 19 th century. However, some Muslims got acquainted with the European culture without intermediaries in the early 20th century. Rich families of entrepreneurs visited European countries to both see them and for trade. And their children went there to study.

By the end of the 19 th century, Tatar entrepreneurs seriously changed the specifics of their activity. It was explained by different factors. First of all, because of consequences of the industrial revolution, as a result of which many Tatar factories went bankrupt. Secondly, due to the expansion of the state border in the East of the Empire, trade in Central Asia, that is to say, within Russia, became not very profitable for Tatar merchants. This is why they started to look for new markets. So the word 'Europe' started to be used in the Tatar merchants' vocabulary more often.

Many Tatar merchants made attempts to conquer the European market. The Khusainovs – millionaires from Orenburg – failed the commercial experiment, while Kazan merchant Shakir Kazakov was luckier. His youngest son Mukhammed Kazakov opened petty commerce in Germany in 1910. Later he even married a German girl. Merchants the Taneyevs, Kastrovs, Akbulatovs sold their goods to western countries.

But adventurous Tatars in Europe were interested not only in buyers of their goods but also technologies. For example, Orenburg owner of gold mines Shakir Ramiev visited Western Europe to know the local gold mining business and purchased vehicles of foreign origin for his production.

French universities

By the 19 th-20th centuries, many people understood that they could not run commercial business in the old way. This is why merchant and millionaire Akhmed bay Khusainov, who even did not know how to read (consequences of studying in a Kadim madrasa) expended hundreds of thousands of rubles on the organisation of a Jadidist madrasa and scholarships for Muslim students at universities. He also asked Kayum Nasyri to translate the basics of accounting in Tatar. National progress became the major ideology of the Tatar society of the beginning of the 20th century. Admitting the technical underdevelopment of their nation and drawbacks of the educational system, Tatar merchants sent their children to Europe.

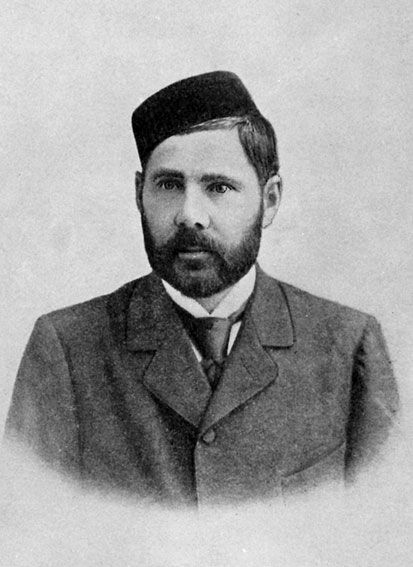

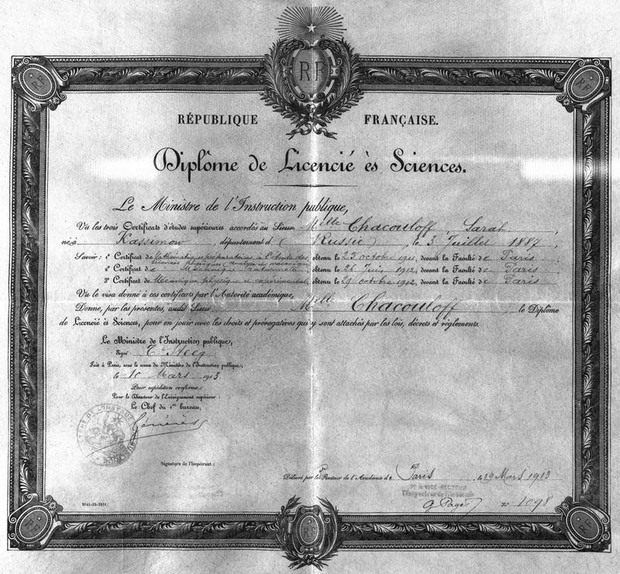

For instance, Ismagil Karimov, a son of a Kazan publisher, studied typography in Leipzig. Sons of the owner of gold mines the Ramievs studied mining in Switzerland. And even the first feminine mathematician Sara Shakulova, a daughter of a Kasim entrepreneur, studied at Sorbonne. But later in Russia, she had to prove the compliance of her diploma with the Russian requirements for higher education for a long time. Having passed all exams, she got a Russian diploma too.

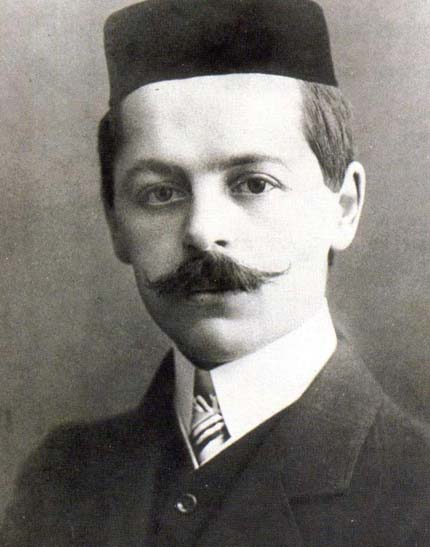

Graduate of the Kazan Tatar Pedagogical School Sadri Maksudi reached Istanbul first and then went to Paris to study. What is more, Ismail Gasprinsky advised him to go directly to France. But he did not listen to him. However, in Istanbul, famous Turkish writer Ahmed Midhat repeated Gasprinsky's words. ''All sound people have gone there. France is the most civilised country in the world, and the Paris university is the best in the world. If you study there, you will have authority both here and on your homeland,' Maksudi's daughter tells in her memories. As a result, Maksudi became a world-class lawyer. The fate of public activist Yusuf Akchura was analogous. He also studied in Paris.

European Terra Incognita

Apart from business trips at the beginning of the 20 th century, rich people could afford themselves a simple trip to Europe. Trips became a compulsory part of self-improvement among wealthy and smart Tatars. For example, publisher Akhmetgaray Khasani travelled in Germany, France and Switzerland for two months in 1910. In his letter to his wife Zaynab, he wrote they could buy a lot of vegetables for a good price, but his friends and he could not buy many things abroad because of the customs duty. After the trip, Khasani told the European culture and countries did not interest him like they used to and that there were few things that could surprise him. ''I won't change my homeland for them. My homeland has everything I want,'' he wrote.

Meanwhile, Kazan merchant Gabdelkarim Yunusov went to Berlin to receive treatment in 1911. Earlier he talked to different specialists: from Chinese healers to Moscow and Warsaw doctors. As a result, he was treated in one of the private German clinics.

Personal belongings of Kazan merchant Abdulkhamid Apanaev are kept at the Kazan National Culture Museum: a huge suitcase, wooden box with a lock to store documents and different souvenirs like a shell of sea tortoise, shark tooth, a miniature of monkeys made of ivory and other items. There is an album in French called As a Memento of Paris about architectural and historical landmarks of the city with Apanaev's note '1905'.

Writer Fatikh Karimi who accompanied Sh. Ramiev in Western Europe as a translator published his travel diary. Karimi's Trip in Europe was published in 1902. The author constantly compared the European progress with the development of the Tatar and Russian societies, noted the underdevelopment of the latter. He was amazed at the German education, French culture and commercial schools in Belgium. He almost married a French lady.

Subsequently, F. Karimi became chief editor of Ramiev's newspaper Vakyt and there he continued to write about the European progress, the main lever of which was enlightement. ''They (the Europeans — L.G.'s note) did not spend their time for empty discussions, like what pants or suit, length of mustache or hair,'' wrote Karimi. It is obvious that his publications played a role in the promotion of Europe among the Tatars.

For example, in the Kazan madrassas Muhammadia they discussed the introduction of teaching of the basics of the English language. In the madrasas Izh-Bubi, Vyatka Governorate, they studied German and French on a voluntary basis. An Ufa scholar Ziya Kamali was a fluent speaker in German and French.

The war – a chance to see ''Aurope''

Wealthy families could afford foreign teachers. For example, children of Trinity merchants Yakushevs in the 1910s were brought up by governesses brought from France. This practice of some merchants of Kazan had existed before. It is known that a Kazan merchant Izmail Apakov, who lived in the second half of the 19th century, spoke perfect French. At the beginning of the 20th century, the document about the arrival of Turkish Hilmi Pasha in Kazan says that two Tatar women — Yunusova and Bogdanova – spoke to him in French.

The image of a distant and beautiful 'Auropa' for the Tatar culture was a symbol of national development and progress. With the beginning of the First World War ''La Belle Epoque'' ended including for a few of the Tatar bourgeoisie and their inner circle.

During the war, the Western world became more tangible and close: tens of thousands of Tatars from ordinary families joined the ranks of the Russian army, and some of them saw ''Aurope'' in the flesh. The First World War became one of the greatest tragedies of the mankind and a kind of discovery of other cultures. Drafted from different countries and continents soldiers, representatives of various nations and faiths, under forced conditions of war and captivity became acquainted with the world of the 'others'. But their experience should be analyzed in the context of the Soviet culture.