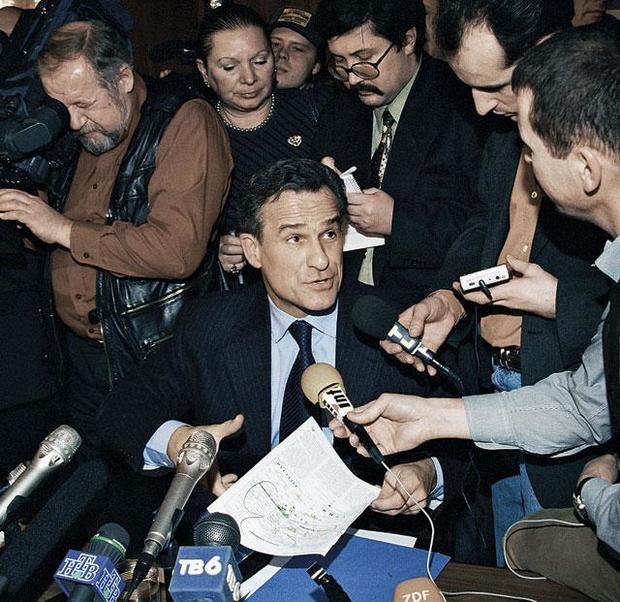

Sergey Yastrzhembsky: ‘I haven’t met with Mr Putin since 2008’

A documentary feature Ivory. A Crime Story, made by the team of former presidential aide to Vladimir Putin and now successful film director Sergey Yastrzhembsky was submitted to the Oscar long-list and contends with the feature produced by Leonardo DiCaprio. Realnoe Vremya discussed with Yastrzhembsky how elephant hunting and documentary film directing combine, when he met with Mr Putin last time and many other topics.

'I've hunted elephants in the places where there is an overabundance of them'

Mr Yastrzhembsky, you are a votary of hunting and, at the same time, you care about the environment protection. Doesn't it contradict? Perhaps, did you give up hunting because of all you have seen?

No, I didn't give up hunting, and there is no contradiction. Moreover, the second point follows logically from the first because many hunters seeing what is happening with the wildlife, seeing the threat of extinction of certain species, they are first to exclaim for the protection of animals. Hunting, as you know, cannot exist without wildlife, and in order to ensure that this hunting existed, you need to take some measures to protect these wild animals.

Trophy hunting, which I do, as thousands of people around the world, involves the unconditional payment for this expensive pleasure. Part of this money go for preserving of the wildlife and protecting animals from poaching. If there is no hunting (such a paradox, maybe for some ignorant people) — there will be no wild animals. Moreover, they will disappear very quickly. Trophy hunters are a barrier between wild animals, poachers and local communities in Africa and Asia. If they lost their economic value (and it depends on hunting), then they would be destroyed. Animals are very often seen by the local population as competitors in the struggle for access to water, pastures. Therefore, if there is no hunting, the local population destroys them.

'Animals are very often seen by the local population as competitors in the struggle for access to water, pastures. Therefore, if there is no hunting, the local population destroys them.' Photo: yastrebfilm.com

Mr Yastrzhembsky, why have you become so interested in documentary film directing?

Perhaps, from journalism, because I have spent many years in this field. I've worked for seven years in Prague in the journal 'Problems of peace and socialism', then I had my VIP magazine for the leaders and about the leaders, who still exist today. I wrote a lot in different Russian editions. In general, in my opinion, journalism is very close to the documentary. The documentary is also one of its kind of journalism. Just movie use a different language — the language of images. Journalism, in the classical sense, is a more dry type of creativity.

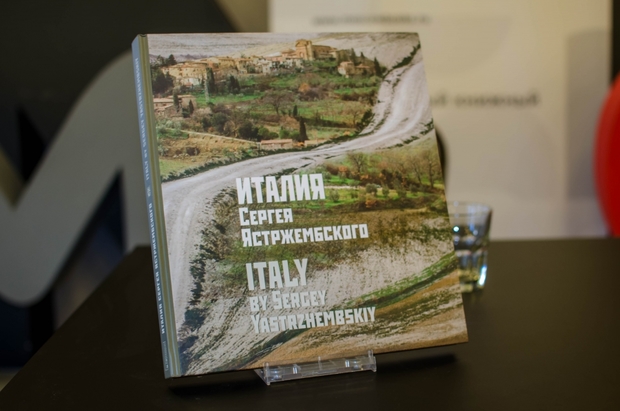

The second 'source' is that I've been seriously into photography — I have a name that has been earned at dozens of exhibitions. There are about eight or nine solo albums that I released. It is also very close to the documentary.

'I've been seriously into photography — I have a name that has been earned at dozens of exhibitions. There are about eight or nine solo albums that I released. It is also very close to a documentary.' Photo: dolcevita-magazine.com

And third, documentaries, unlike fiction, allows to speak about many real problems plainly, firmly and truthfully. Of course, if you shoot a real documentary, not engaging in the political correctness. Here I like that too.

'I haven't met with Mr Putin since 2008'

For several years, you held high positions in the government: could you tell us how and why you made the transition from policy to ethnography, photography and directing?

I devoted 30 years to the public service, as an ambassador and as an official in the presidential administration, as the press secretary of the president and his aide. I think that is enough time to approve yourself in public service. After these years I feel like I have accomplished much in this field.

I just wanted, while there are time and health, to try myself in different spheres — that's why I chose photography, documentary film, ethnography, travelling, protection of the wildlife — that is, the topics that have always been close to me.

In your presence, there was the resignation of Yeltsin, you were his aide, and then took a similar position already under Putin. Years later, what can you say about that transition period?

Well, Russia is constantly in some kind of transition — I have such impression. I think in that transition period it is necessary to evaluate the courage of the first president of Russia, who, having found a successor, knowing that physically he was not ready to continue to fulfill his obligations, ahead of schedule handed over power into the hands of Putin and set a very interesting precedent and, I think, noteworthy in Russia. It is hard to imagine other political figures of the same period who would be able to do it.

Do you keep in touch with former colleagues? Have someone of them left in the apparatus?

Of course, there are some. Occasionally, yes, I do maintain contact, but they are very rare.

What about Mr Putin?

I haven't met with Mr Putin since 2008.

'Tens of millions of dollars' burnt

Did you expect that you would be submitted in the Oscar long list? Perhaps at the stage of creation of the film, there was some hope?

No, I did not. When you create a feature, you think about how to do it, and then think about what festivals to promote it in, and you don't even think about awards. Here's how you do your job, then you can do the next step. There is a rigid periodization, therefore, starting a feature, I think few people think about future rewards.

Why have you become concerned with the problem of the destruction of elephants? What resources were used in creating the film?

As for the film itself, we started to shoot it three years ago. By that time, my studio had already had a large amount of films that we shot, including in Africa, by the time we had filmed about 70 films. The shooting took place in 30 countries around the world. The operators alone we have worked with are 30 people from different countries — a truly international team, international project.

Having made a film in the style of a journalistic investigation, we traced the chain of the crime: from the place of origin — in savannah or in the forests of Africa, where there are poachers, then we show how the illegal ivory comes in various transit countries, for example, in the Philippines, and then we traced its path to the main consumer of all legal and illegal ivory, which is China — more than 90% of illegal ivory goes to China. Thus, we had a full journalistic investigation of the crime from the beginning to the end, when we show the process of the sale of illegal ivory and items made from it.

Of course, we noticed this problem by chance. The thing is that for many years I have been engaged in hunting, and in 1997, I opened my African hunting by the trip to Tanzania, the famous Selous Game Reserve. I was amazed by Africa itself, as they say, 'crushed' on it. At the same time, I was amazed by the number of elephants that I saw in Selous. In fact, on each day of hunting we saw large groups of elephants. In several years I came again — it was somewhere in 2013, and saw a completely different picture. First, there was a large number of hyenas, for two weeks I did not see a single living elephant. Hyenas multiplied due to the fact that there was just a massacre, the mass destruction of elephants. During this period, the number of animals in Tanzania decreased dramatically — from 100 thousand to 12-15 thousand. By that time, I began to come across materials that talked about an incredible boom of poaching in Africa. That's why I started to shoot this movie.

New York Times in its review wrote about some the roughness, unevenness of the filming — what do think about that remark?

The uneven filmmaking is completely obvious. One-third of the material was filmed with a hidden camera. When you shoot with a hidden camera where it is not allowed to shoot, where you can just physically pushed out, relatively speaking, from a jewellery store or from a workshop, where they work with illegal ivory, you can not ensure the quality of the filming. Journalistic investigation suggests that there is unevenness in the filming. It's not a parquet shooting, this film was shot in very difficult conditions.