Kirill Chunikhin: “Americans wanted to explain unfamiliar art”

A book by Kirill Chunikhin, “American Art, the Soviet Union, and the Canons of the Cold War," was presented in Moscow.

In Moscow, a conversation took place between Soviet art historian Nadezhda Plungyan and the author of the book “American Art, the Soviet Union, and the Canons of the Cold War," Kirill Chunikhin, dedicated to how perceptions of American and Soviet art were formed during the Cold War. The participants discussed why American art in the USSR turned out not to be so “abstract” as commonly believed, how the myth of Jackson Pollock as an “ideological weapon” arose, and the persistent bipolar opposition of American and Soviet art. Details are in the report by “Realnoe Vremya” literary critic Ekaterina Petrova.

How a Dissertation in English Grew into a Book in Russian

Kirill Chunikhin's book “American Art, the Soviet Union, and the Canons of the Cold War” grew out of dissertation research. It was written and defended in English: “I am a graduate of the European University, but I wrote my dissertation in English and defended it in Germany. Since the dissertation text itself was in English, it greatly influenced the book — its structure and the argumentative clarity I tried to achieve.” According to Chunikhin, academic writing in English required significant effort and determined the analytical logic of the future monograph.

The English-language version of the book was published in 2025 in a series dedicated to the Cold War. Chunikhin noted that the moment of publication turned out to be difficult: “It was a period when publications by Russian scholars were often called into question.” The Russian edition appeared in the same year, but slightly later in the series of the journal “Neprikosnovennyi Zapas” library by the publishing house “Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie.” The translation was done by Tatiana Piruskaya with the participation of a literary editor.

The author emphasized that he was not directly involved in translating the text, but working on the Russian version became a separate stage for him: “Reading the translation of my own text into Russian helped me better understand some things I studied.” He characterized the Russian edition as an adapted translation of the English monograph: context necessary for the Russian-speaking reader was added, whereas in the English version some plots well-known to the Russian audience were, conversely, explained in more detail.

Speaking about the book's reception in America, Chunikhin drew attention to the difference in academic contexts. He noted that although the book was written by an art historian, it was consciously addressed to a broader humanities audience: “I rewrote all of this, targeting a conventional historian who has an interest in the topic but no art history training.”

At the time of the presentation, the book had only recently been published, and it was too early to speak about its established reception in the American academic community: “Journal reviews will come later because that takes time. I can't yet say how the American academic community has reacted to it.”

At the same time, Chunikhin stated the key research thesis, the testing of which was supposed to become the subject of future discussion: “I show in the book that American art history and theory were formed in part due to an orientation toward the Soviet Union. The very precedent of opposing Soviet and American art largely defined the contours of modern American art history.” He emphasized that the Soviet Union in this process was not an “invisible” object but performed a structure-forming function.

Jackson Pollock as an “Ideological Weapon”

One of the key plots in Kirill Chunikhin's book is related to the figure of Jackson Pollock and the persistent idea of him as an “ideological weapon” of the Cold War. Soviet art historian Nadezhda Plungyan recalled that in the Soviet context, this image was formed against the backdrop of a long-standing anti-modernist policy: “Anti-modernist campaigns regulated Soviet art policy for several decades; they were accompanied by special publications and mass print runs. Formal experiment, primarily surrealism, was removed from the legal field and declared a hostile diversion.”

Within this logic, the widely spread narrative about Pollock as a consciously anti-Soviet artistic phenomenon arose, which Chunikhin's book called into question.

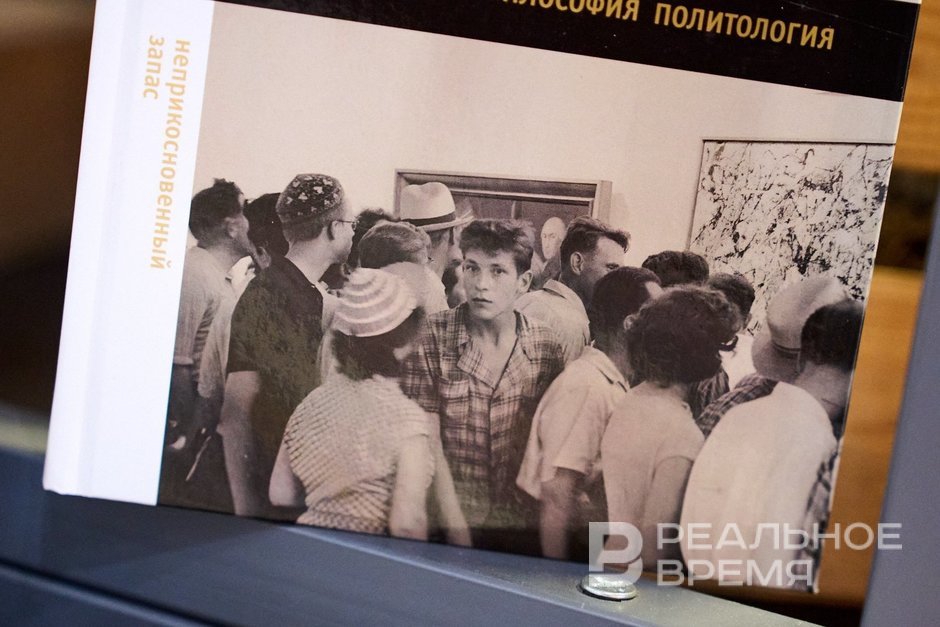

The author himself emphasized that this plot was embedded at the level of the visual design of the Russian-language edition: “The illustration on the cover of the Russian version is a visual epigraph to the argument I am trying to deconstruct.” He described the common narrative as follows: Pollock's radical artistic language was supposedly capable of undermining the legitimacy of the Soviet regime, since abstract art and Socialist Realism were thought of as irreconcilable opposites. Chunikhin noted that such a binary opposition is often used as a universal tool for describing 20th-century art and is especially easily reproduced in the context of the Cold War.

Work on the book began with an attempt to test this approach at the factual level. Chunikhin said: “When I began closely engaging with the materials, I initially also tried to find evidence that Jackson Pollock was used to undermine Soviet ideology.” However, further analysis showed that the historiography of this thesis relies on an extremely limited set of sources.

Kirill Chunikhin pointed to a 1972 article by American critic Eva Cockcroft, which claimed that the CIA used American art against the Soviet Union, but emphasized: “When you read her text, you find no sources except mentions of affiliations of certain Museum of Modern Art employees with the CIA. No direct connections have been established.” According to him, subsequent authors repeatedly reproduced this reference without supplementing it with empirical data, shifting the conversation into the realm of speculation.

Chunikhin separately addressed Frances Stonor Saunders' book “The CIA and the World of Arts," which played a major role in popularizing this version. He clarified that, despite the volume and popularity of the publication, “the part related to painting and Pollock occupies about fifteen pages, and there are no facts there either.” Nevertheless, it was from these works, he said, that the persistent stereotype of the “subversive” potential of abstraction grew, which continues to be reproduced in research.

In Chunikhin's book, this was contrasted with an analysis of archival documents from the United States Information Agency — a structure that handled cultural exchanges with the Soviet Union. The author emphasized the fundamental significance of the sources: “The archives are open, accessible, declassified, and they allow reconstructing the internal logic of decision-making by American art curators.” From these materials, it followed that the task was not to compromise the Soviet system but to explain American art to the Soviet audience. “The Americans did not try to undermine or compromise. They wanted to explain art that was unfamiliar to the Soviet person and promote its positive reception," said Chunikhin.

The second part of the book is dedicated precisely to this reconstruction: working with correspondence, draft catalogs, principles of artwork selection, and Pollock's actual place in exhibition strategies. Based on these documents, according to the author, a “different story” was built, which did not fit the scheme of Pollock as a tool of ideological subversion and allowed considering his role in the context of institutional and interpretative practices of American cultural policy during the Cold War.

American vs. Soviet

One of the central questions in the conversation between Chunikhin and Plungyan was the opposition of American and Soviet art and how this opposition actually functioned in the Soviet context. Nadezhda Plungyan drew attention to the discrepancy between the ideological scheme and actual artistic practices: “American art brought to the Soviet Union in the 1960s was not so non-objective. There was a large number of American realists selected by Soviet art critics for the exhibition in Sokolniki.” According to her, the book shows in detail that the actual composition of the exhibition contradicted the rhetoric about total abstraction, and this rhetoric itself continues to be reproduced today as an unchecked cliché from the 1960s.

In the book, this gap is examined in the broader context of the anti-modernist campaign. Plungyan emphasized that discussions about the “corruption” of the Soviet viewer by abstract art became a persistent motif in late Soviet criticism: abstraction was viewed as a threat to consciousness and personality. At the same time, anti-modernism, especially in the post-Stalin period, had a dual nature. On one hand, it continued a harsh ideological line; on the other, it produced extremely detailed and professional descriptions of Western art: “It was modernism with a minus sign — the positive world of socialist realism and the negative world of modernism, which everyone was supposed to know.”

Kirill Chunikhin proposed viewing this corpus of texts not only as an ideological by-product but as an independent tradition. He noted: “In the Soviet Union, there were entire departments in institutes that for decades were engaged in explaining why this art is not art.” According to him, if this rhetoric is analyzed seriously, internal logic and characteristic inconsistencies are revealed. That is why he insisted on using the term “anti-modernism” as an analytical concept, not a journalistic label.

A crucial observation for the book was about how Soviet criticism was unable to conceive of abstraction as art that does not appeal to reality. Chunikhin illustrated this with the example of an anti-modernist cartoon where an abstract artist “paints” a distorted version of Perov's painting with his foot: “The abstraction in this cartoon is not abstract art, but a poor-quality figurative image. Here, the discourse betrayed the impossibility of imagining art not connected to reality.” He emphasized that in the Soviet optic, abstraction simply was not read as an independent artistic language.

This conclusion was also supported by reactions to the exhibition of American art in the USSR. According to Chunikhin, a careful reading of comment books and criticism shows that abstraction aroused minimal interest: “Even when Nikita Khrushchev was at that exhibition, abstraction did not touch him at all. He was outraged by a sculpture.” Khrushchev and Soviet viewers reacted primarily to distorted figurative images, which were perceived as a violation of familiar ideas about the body and beauty. Abstraction, on the other hand, was evaluated formally and neutrally, as “doodling," lacking offensive potential.

In this context, Chunikhin linked the Soviet reaction to a deeper aesthetic orientation. He referred to Nadezhda Plungyan's thesis that Soviet culture at the crossroads of expressionism and symbolism chose symbolism. Materials from American exhibitions, he said, indirectly confirmed this: expressionist deformation of the figure caused sharp rejection, whereas abstraction remained almost unnoticed. A characteristic example cited by Kirill Chunikhin was the scandal at the Manezh in 1962, when Khrushchev's anger was provoked not by abstract works but by the figurative “Nude in an Armchair” by Robert Falk, in which he saw an “American trace.”

In the end, as Chunikhin emphasized, the opposition of American and Soviet art in reality did not work as the ideological scheme assumed: “We say that abstraction is what can undermine, but it turns out to be passive and even unthinkable. Reaction was caused by the distortion of reality, not the rejection of it.”

Ekaterina Petrova is the literary critic of the online newspaper “Realnoe Vremya," host of the Telegram channel “Poppy Seed Buns.”