Reading the novel Orbital with a globe at hand

Space engineer Alexander Khokhlov explained which historic moment in space Samantha Harvey captured in the novel Orbital and how Russian cosmonaut Sergey Krikalev became the prototype for one of the characters

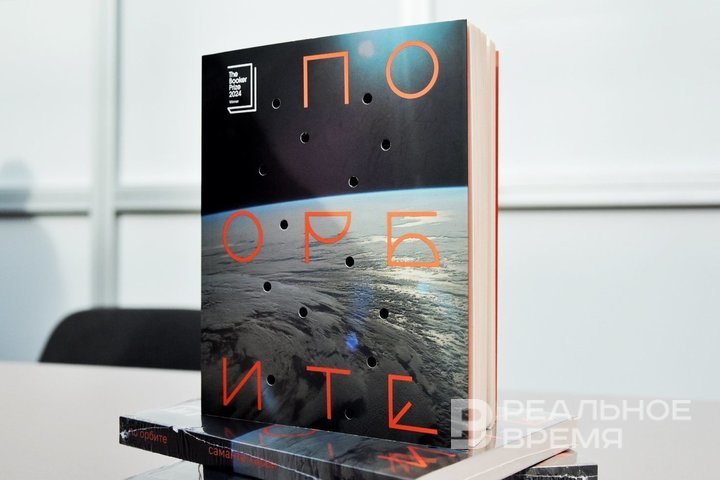

In 2024, British author Samantha Harvey received the International Booker Prize for her novel Orbital. This year, it was published by NoAge, which presented the book at the International Intellectual Literature Fair non/fictioNvesna alongside space engineer Alexander Khokhlov. How accurately the novel Orbital reflects the real lives of cosmonauts and astronauts on the ISS is explored in a report by Realnoe Vremya literary columnist Ekaterina Petrova.

Sixteen sunsets and six people in orbit

At the centre of Samantha Harvey’s novel Orbital, there are six people aboard the International Space Station. Two Russian cosmonauts and four astronauts: an Italian, a Japanese woman, an American, and a British woman. In 24 hours, they witness sixteen sunsets, sixteen sunrises, and they reflect. On Earth. On people. On themselves. “They become our eyes, ears, and guides to this extraordinary world,” said Yulia Kuzmina, who represented NoAge publishing house at the presentation.

Harvey avoided direct references. Neither the ISS nor the Soyuz are mentioned in the text. Instead, there are “ships” and a “station” — deliberately blurred outlines, as if intentionally vague. This abstraction, according to space engineer and populariser of astronautics Alexander Khokhlov, is a device used to lift the theme out of technical documentation and translate it into a universal poetic register. And yet, the novel’s texture is firmly embedded in a specific historical moment.

The crew of six is not fiction. It really happened. And not in theory, but during a specific two-year period when two Soyuz spacecraft were simultaneously in orbit, each carrying three people. One Russian and two representatives from other countries. This was the time when Russia was fulfilling its obligations under the Sea Launch project — a large-scale endeavour that allowed satellites to be launched from the equator. A dream of the 1990s, the international consortium eventually passed to Russia. Near Vladivostok, it was in its final days. Under the contract, while the debt was being repaid, Russia sent foreign astronauts on Soyuz flights. This was before Elon Musk’s Crew Dragon. Back then, only Soyuz spacecraft flew. Each had one Russian onboard. And the crew formula was 1 + 2. Then again, 1 + 2.

During the pandemic, when borders were closed, planes remained in hangars, and streets were empty, Samantha Harvey tuned into a live broadcast from the ISS. The station’s slow drift — orbit after orbit. “The author found the ISS broadcast online, immersed herself in watching, started searching for photos. She became so captivated by the subject that the result was a small but very poetic novel, Orbital,” said Kuzmina.

Khokhlov was among the first to read the novel, before its official release. He did not know what to expect. “For me, it was a surprise. I saw that the Booker Prize had already been announced. Excerpts about the book had appeared in the media. But those reviews were as abstract as some parts of the book. It is feelings, emotions, and reflections,” said the space engineer.

After reading the novel, he deliberately revisited an interview with Harvey, where she explained her doubts. She hesitated, fearing she might get space wrong, inaccurately or incorrectly. In the end, she decided to go ahead and started writing. Alexander Khokhlov noted that the book contains many stereotypes. “We all have stereotypes about astronautics, shaped by inaccurate films and articles that distort reality. We watch movies like Gravity or The Challenge, and form certain ideas in our minds. But in real life, it is different,” he said.

The same applies to the book. Harvey’s stereotypes, like all of ours, stem from a shared information environment: articles, trailers, Hollywood constructions. Even Khokhlov admitted that shedding stereotypes is difficult, even with his experience. He spoke about this without reproach — as something natural, even logical. Because what matters in the book is not what is written, but how it is written. It is a novel about perspective. About observation. About those who drift in the darkness and look down — at the lights and scars of civilisation. At Earth, where nearly eight billion live on the edge of anxiety. And above — six people. They fly. Around the planet. Around meaning. Around themselves.

Noise, borscht, and overloads

There is no personal space in orbit. And no way to escape, even if one wishes to. In Samantha Harvey’s novel, one of the characters loses a loved one and cannot return. He remains surrounded by instruments, cameras, schedules, and people with whom he shares air, food, and fragments of sleep. “People on the ISS become each other’s mother, father, doctor, psychologist, and closest companions,” said Yulia Kuzmina.

The novel describes what it is like to be in a confined space with no right to show weakness. To live through grief while remaining a function, a crew member, part of a team. Alexander Khokhlov confirmed that the psychological pressure is among the most tangible challenges. “Of course, it’s not easy for them there,” he said. The history of manned spaceflight includes cases where crews argued and conflicted not only among themselves but also with Mission Control. “The crew starts to act up, communication becomes unpleasant, and they do not always follow all Mission Control’s instructions,” Khokhlov explained. This happens more often than is commonly believed.

Psychological compatibility is tested through experiments. One of the most famous is Mars 500. Another is Sirius. These trials take place at the Institute of Biomedical Problems, located between the Shchukinskaya and Polezhayevskaya metro stations in Moscow. International crews are confined there to understand how people of different nationalities coexist in a confined space. “Some experiments ended very badly; things went so poorly that crews separated and even closed hatches between themselves,” Khokhlov recalled. There are “disturbing stories” about these isolations circulating online.

To prevent worse outcomes during actual missions, future cosmonauts train together — in Russia, the USA, Europe, and Japan. They have time to get to know each other. Some form close bonds, while others remain formal colleagues. “This happens especially often now, when Soyuz and Crew Dragon spacecraft fly, and often the Crew Dragon crew barely knows the Soyuz crew,” Khokhlov said. Contact between the segments is minimal. Everyone works within their own areas. But one common point of connection remains — the dining table.

“Cosmonauts and astronauts organise their day so that lunch or dinner is spent together in one place,” explained Alexander Khokhlov. Sometimes they have lunch in the American segment and dinner in the Russian one, or vice versa. It all depends on the arrangement. This is not a ceremony, but an effort to preserve humanity and not get lost in the routine. Eating together means reminding yourself that you are not alone — that the crew is not an abstraction, but people.

Harvey’s novel reflects these shared meals and food — borscht and barley porridge in orbit. Everyone’s rations are standardised but vary depending on the country. Soups, porridges, and similar dishes repeat regularly. According to Khokhlov, variety is rare. To diversify their diet, the station temporarily becomes a gastronomic exchange. “Americans take food from their packs and give it to the Russians, and the Russians take from theirs and give it to the Americans,” Khokhlov explained. There was even an occasion when a Japanese astronaut “bartered all the fish from the Russian segment,” trading it for chocolate or something else. He missed fish, while the Russians traditionally have plenty of canned fish.

But taste is not the main sensation in orbit. The main factor is noise. The station is constantly noisy. It is the life support system, ventilation, and equipment. The noise is so loud that the crew cannot be there without headphones. Cosmonaut Kirill Peskov recorded a video for his Telegram channel. According to Khokhlov, the sound was comparable to the noise at a book fair. To work, they have to use earplugs or wear noise-cancelling headphones.

Space is not silence. It is the pressure of noise, weightlessness, and constant monitoring. “Everyone who dreams of flying into space wants to experience weightlessness. But it is the most difficult thing about space,” said the space engineer. It is beautiful, it is alluring. But it is also what destroys the body, causes atrophies, and disrupts the balance system. Cosmonauts love weightlessness, but they suffer from it. It is both a reward and a punishment.

“Working with their hands”

Samantha Harvey mentioned the work of cosmonauts in orbit in broad terms in her book. “By the way, the book places quite good, accurate emphasis. The point is that there are long-term experiments on the ISS that are repeated from one expedition to another,” noted Alexander Khokhlov. He himself chronicled the ISS for the magazine News of Cosmonautics for nine years. Nine years — and every month, his materials featured the same experiments. Because science in space is not about thrilling discoveries. It is about repetition. Multiple, methodical, inevitable. Alongside this, there are short-term studies focused on individual astronauts. Europeans, for example, regularly arrive with their own scientific equipment, for which a unique programme is prepared.

Alexander Khokhlov explained that the crew’s work is divided into three main areas. The first is routine. This includes technical maintenance of the station: changing filters, checking life support systems, and conducting medical examinations. According to the space engineer, this is similar to car maintenance. Without regular attention, the station simply cannot function. The second area is science. Cosmonauts are not researchers in the traditional sense, but rather laboratory technicians. They receive instructions, materials, and equipment. They assemble experimental setups, adjust cameras, and run broadcasts for scientists on Earth. Occasionally, they work manually. “If any operations require manual work, then they roll up their sleeves and get to work,” Khokhlov added.

The third area involves dynamic operations, primarily docking procedures. This is especially true in the American segment, where some spacecraft are docked manually by astronauts from the observation cupola. It was here, Khokhlov noted, that the poster for the film The Challengewas filmed — in that very module built by Italians for NASA. “A cargo spacecraft approaches and hovers, two astronauts sit in the observation cupola, looking through the windows and monitors, and control the docking of the spacecraft using a joystick,” Khokhlov explained.

How Sergey Krikalev made it into the novel

Within Harvey’s book, there is a figure who appears more than once — Sergey Krikalev. His portrait hangs at the workstation of one of the characters, and the character himself bears a strong resemblance to Krikalev. Samantha Harvey clearly chose him deliberately. Why? Khokhlov offered a personal theory, immediately clarifying that this was not an official explanation but his own assumption: “The first British astronaut was Helen Sharman. She flew to the Mir station in 1991. And Sergey Krikalev was there with her.”

During that mission, Krikalev stayed on board longer than usual because he gave up his seat to another astronaut. From the perspective of the young viewer from misty Albion, it was a historic event. Perhaps this impression left a mark on the young Samantha’s mind. “Most likely, she was watching TV and saw that next to their lovely Helen Sharman stood a handsome, tall, stately Russian cosmonaut with a good voice,” suggested Alexander Khokhlov.

There were other reasons to remember Krikalev afterwards. He became the first Russian to fly on an American shuttle. He participated in the first opening of the hatch between the American and Russian segments of the ISS. He was part of the first long-term expedition. He worked in the highest positions at Roscosmos. And importantly — he spoke English well. Today, Sergey Krikalev is the deputy head of Roscosmos for the manned program. He is responsible for everything. This is felt in Harvey's book: it is no coincidence that he became a role model.

The novel Orbital describes how cities and natural phenomena are visible from the station. “They see the Earth and large objects, but on the illuminated daytime side, cities are not visible to the naked eye," Khokhlov said. To see something clearly, television cameras and a large lens are needed. Cosmonauts take many photographs. And even with a lens, it takes only a few seconds for the city to come into focus. Everything is very fast. Minutes are already a luxury. “The moment when the city can be well photographed is seconds. The time when the city is conditionally visible is minutes," Alexander explained.

To read Harvey’s novel at maximum depth, Khokhlov advises placing a globe nearby. And literally tracking the station’s route, as they do in reality. Then the plot gains dimension and connection to the real world. “When you read the book Orbital, take a globe. Place it next to you. Then you will understand why," the space engineer advised.

In November 2025, it will be 25 years since manned flights to the ISS began. This date almost coincided with the publication of the novel Orbital. A work of fiction, but with precise historical reference. Reflective, yet based on concrete data. Written on Earth, but from the perspective of those in the sky. Between sunrise and sunset. Between voice and silence. Between six people in orbit and billions left below.

Ekaterina Petrova is a literary critic for Realnoe Vremya online newspaper and the author of the Telegram channel Buns with Poppy Seeds (Bulochki s Makom).