Soviet economy uncensored: how the USSR’s economy worked

In the book The Great Soviet Economy. 1917–1991, Alexey Safronov tells the story of the Soviet state’s economy from beginning to end

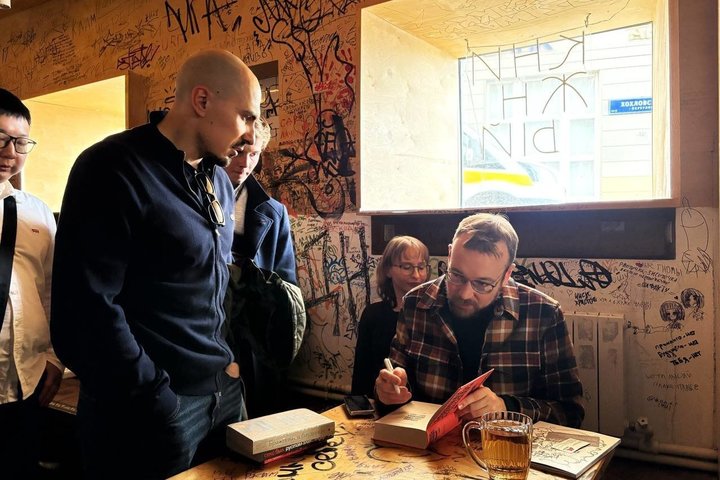

At the Brazhniki — and Get Drunk! festival in Moscow, Alexey Safronov presented his book The Great Soviet Economy. 1917–1991, published by Individuum. It is a detailed, coherent and human story of how the Soviet state tried to invent its own economy and what we can learn from it.

Shock, queues, and bright pink ham

Alexey Safronov was born in 1987 — too late to remember the USSR, but early enough to remember its collapse. Not in numbers, not in charts, not in industrial production indices. In the sickly pink ham. In the queues. In the strange childhood feeling that the adults were hiding something. “My earliest memories are of the collapse. Not of the economy — I didn’t know any smart words then. But there was a feeling that all the adults around were stunned,” Safronov recalled.

That feeling later grew into a profession, and then — into a book. A memory of canned goods from American humanitarian aid, of trips to the other side of Moscow to “get hold of” food through the back door of a shop where someone had connections. His interest in the Soviet economy didn’t begin at university. And not with a dissertation. First came an office job. And eight hours with no work.

Safronov worked at PriceWaterhouseCoopers — international consulting, status, ambition. “For a student, getting into international consulting was a big deal,” said the author of the book. But at the end of 2008, everything collapsed. The crisis came just like in the textbooks, but no one offered any explanations. At work, he had to sit in the office, even though there work. Out of boredom, Safronov began to read — everything he could find about the crisis, about the economy, about the structure of the system that had collapsed.

But the real point of no return came later — when he began writing his dissertation. The topic was budgetary investments. According to all the guidelines, the effectiveness of a project had to be assessed based on future income. But what if the road is free? What if it’s a children’s clinic? Then it’s considered ineffective. So — should it not be built? “I realised that such efficiency metrics are completely unsuitable for public spending. They were copied from private companies, where efficiency is measured by future income. It’s an obvious absurdity,” explained Alexey Safronov.

But it turned out that everything had already existed. Methodologies, approaches, documents. They were forgotten, discarded, reset. “In public administration, there are many cases where people reinvent the wheel. Even though it was thought through 50 years ago and documents were adopted. But then everything fell apart, was forgotten, and now the cycle is starting again,” Safronov said.

This is how the idea for the book was born. Not about economics as a science. And not about the Soviet Union in ideological terms. But about a thorough, precise, and detailed history of Soviet economic thought and practice. About how it began, what problems it faced, what it tried to solve, and why it ended, one way or another. “This is not a book about economics. It is not an economic book. It is a book about history — the history of economics. Economics appears in it as a subject, not as a method, not as a scientific discipline,” the author emphasised.

Safronov was not alone in his questions. It was just that no one had written the answers. There was no such demand in academia. There was no such task in research projects. There was a gap — vast, gaping like an empty space on a bookshelf. “Why should I be the one to do this? Why hasn’t someone else done it?” he asked himself. At some point, Safronov realised that the description of the Soviet economy in historical literature is always a constant “starting from the middle.” Khrushchev and the Virgin Lands. Perestroika and the sudden collapse. “Books about Perestroika begin more or less like this: everyone realised that the Soviet economy was not working. Fine, but how did they realise it? And who is this ‘everyone’? And how long ago did they realise it?” Alexey asked obvious but rarely voiced questions.

The book The Great Soviet Economy. 1917–1991 was born out of a desire to tell everything from the beginning. Not to rewrite, not to interpret, but simply to restore the logic. To show why each idea, each reform, each decision appeared. Because without this logic, Soviet history breaks down into myths. “I felt the lack of a comprehensive perspective that showed the background in every episode,” the author added.

“Cycles of centralisation and decentralisation”

Alexey Safronov proposed viewing the Soviet economy as a single living organism. In his book The Great Soviet Economy. 1917–1991, he sought to capture its essence as a holistic system with its own logic and internal cycles. This perspective is important — not only because it draws a line under the past, but also because it opens a new framework for discussion. “The Soviet economy can and should be considered as a single object,” Safronov said. He refers to Janos Kornai and his work The Socialist System, where socialism is described in static terms, like a snapshot. But Safronov himself follows the “good old principle of historicism” — for him, it is the dynamics that matter. He values the line, not the point. In movement, in evolution and reform attempts, in broken initiatives and the constant struggle between centre and periphery — it is there, in his view, that the true nature of the system is revealed.

One of the key tensions that Safronov highlights was the contradiction between catch-up modernisation and democratic local governance. Modernisation was necessary — for the country’s survival, for development, for breakthroughs, he says. But it also hindered the development of grassroots economic democracy. Too many resources went to the centre. Too little remained locally. “If you don’t have resources that you can distribute, then no municipal self-government will arise,” Safronov said.

The Soviet leadership understood this. Time and again, it tried to roll back: to give local authorities more rights, to allow them to manage finances. But each time, it ended the same way. People began to solve their own problems — “departmental housing,” “social facilities” — and did not fit into the state plans. But the plans had other priorities: the Cold War, the arms race, building factories, space exploration. And every time, local freedoms were rolled back.

This swinging of the pendulum between centralisation and decentralisation, according to Safronov, was the main driving mechanism of reforms. “Cycles of centralisation and decentralisation,” as he calls them. They returned again and again, generating waves of change, and just as quickly disappeared once they had begun. It was not a conspiracy or ill intent, he said, but a structural feature of the system. This is how it breathed.

These attempts to balance governance from below and above were, in essence, a struggle for the legitimacy of power. When people were excluded from economic decisions, sooner or later they stopped feeling that power as their own. “If you do not grant economic rights locally, after some time, not to everyone but to a portion of people, scepticism arises,” Alexey Safronov noted. First comes a feeling of distance — “they are there, and we are here.” Then — a sense of alienation. Finally — indifference. And then, at the moment of crisis, no one steps forward to defend the collapsing Union. Not because everyone was against it, but because it had long ceased to be common.

Here arises another paradox of the Soviet economy: its political stability was long maintained through centralisation, but it was precisely this centralisation that undermined the notion that power belonged to the people. Within this paradox, there lies the same unresolved dilemma: scale versus participation. Grand objectives versus everyday life. Safronov emphasised: “The Soviet economic model is a very broad generalisation. It was different every decade.” In the 1920s — one thing, in the 1930s — another, in the 1960s and 1980s the course changed again. It was not a frozen monolith. It was a system that tried to adapt, reform, and change — though often unsuccessfully. Against this background, a particularly important question emerges: why, despite failures and collapse, does the Soviet economy continue to be revisited? Why is it debated not only by historians?

“All socialist thought is based on a critique of capitalism as an economic system,” Safronov said. He added: “As long as problems keep arising again and again within the existing economic model, this thought will continue to appear.” Today’s Russian economy, in the author’s view, has become a demonstration of the classic failures of capitalism — almost textbook. First freedom, then monopolies, then monopolies merging with the state and beginning to destroy competition. “What we have is a conglomerate of state monopoly — the state plus monopolies that destroy the political system, which in turn destroys the system of free market competition,” Safronov noted. All this is almost a verbatim repetition of a century-long critique of capitalism. And that is precisely why interest in alternatives is inevitable.

Safronov does not offer a ready-made solution. He does not claim to know the only correct path. But he is confident that with or without the book The Great Soviet Economy. 1917–1991, discussions about alternatives will continue to arise — and they can be made more productive, more reasoned, and based on facts. According to Safronov, the economy is not only about money but also about collective imagination, about how power, participation, resources, and the future are organised — and such a conversation truly cannot be concluded. Especially if it is only just beginning.

Ekaterina Petrova — a literary columnist for the online newspaper Realnoe Vremya, the author of the telegram channel Bulochki s Makom (Buns with Poppy Seeds).