‘Between the Prix Goncourt and the Nobel’: BRICS Literary Prize makes an ambitious claim

In Moscow, a new literary prize set to honour authors from BRICS countries has been unveiled

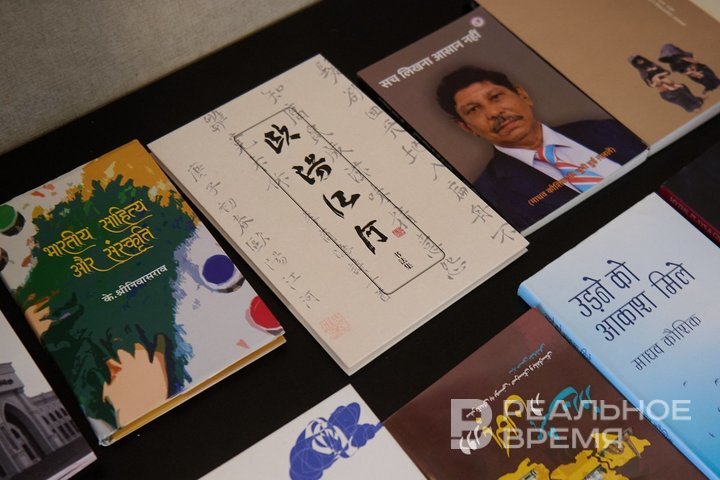

On 30 June, apress conference took place in Moscow where representatives from Russia, Egypt,India, the UAE, and Iran spoke about the BRICS Literary Prize. What this prizeis, how nominees will be selected, why it is needed, and how the organisingcommittee envisions the prize on the global stage — all covered in a report byRealnoe Vremya’s literary critic Ekaterina Petrova.

Who are the judges?

The idea to award a literary prize to authors from BRICS countries emerged after the Traditional Values Forum held in Moscow in the second half of November last year. According to the organisers, the goal of the new Literary Prize is to create a unified humanitarian space among the BRICS member countries, promote cultural exchange, support spiritual, family, and national values, as well as uphold history and culture.

“The BRICS countries are diverse, and I’m sure you are well aware of their geography. They have different histories and cultures. But what unites us is not opposition to something, but common goals, including in the humanitarian sphere. I believe literature is the best medium to offer a deeper understanding of the history, traditions, and culture of the countries that make up BRICS,” said Sergey Stepashin, the president of the Russian Book Union and a member of the organising committee from Russia, at the press conference.

The prize will be awarded annually. Strategic leadership will be handled by the board of founders, which will also form the organising committee composed of representatives from each BRICS country. This committee will manage the prize’s operations, including selecting the jury and secretariat. The main representative of the prize in Russia is the Russian Book Union, headed by Stepashin.

The jury will include at least two representatives from each country. Russia will have seven members: literary critic and director of the V.I. Dahl State Museum of the History of Russian Literature Dmitry Bak; Director General of the Russian State Library Vadim Duda; head of the M.I. Rudomino Library of Foreign Literature Marina Zakharenko; editor-in-chief of the journal Foreign Literature Alexander Livergant; dean of the Translation Faculty at Moscow State Linguistic University Ekaterina Pokholkova; writer Zakhar Prilepin; and executive director of the Translation Institute Evgeny Reznichenko.

“We are focusing on ensuring that the books prepared, written, and winning the competition will be translated into Russian,” added Sergey Stepashin.

The soul of the Russian people lies somewhere between the Goncourt and the Nobel

The head of the prize secretariat and State Duma deputy Dmitry Kuznetsov said that the mechanism of the BRICS Literary Prize will be “somewhere between the Goncourt Prize and the Nobel Prize.” That is, neither publishers nor authors will submit applications; instead, the jury will nominate candidates from each country. Furthermore, the nominations will be for authors themselves, not specific works. According to Stepashin, the main criterion for nomination is the “writer’s contribution to reflecting the spiritual and moral values, history, and culture of the BRICS countries.”

The longlist will include three authors from each national jury. Thus, a total of thirty authors from ten countries will be presented, each “best reflecting the soul of their people.” The longlist will be announced at the Traditional Values forum in Brazil, scheduled for September this year. The shortlist will then feature one author from each country. As Kuznetsov explained, “the international jury at this stage helps select the author who is most likely to ‘resonate’ in other markets.” The shortlist will be revealed during the BRICS House in Shanghai event on 14 October — one month after the longlist announcement.

This is a relatively short time for jury members to familiarise themselves with the works of 30 authors from different countries. The question arises: will they manage to read all these books? And a second logical question: how will they do it? To properly assess literary skills and how each author “reflects the soul of their people,” the books themselves must be read — not just the author profiles prepared by the national representatives. For this, each book needs to be translated into the languages of the BRICS countries. Even if the longlist is ready before September, translating so many books in such a short time is impossible. Then, each jury member must read 27 books (excluding the three from their own country). This also seems unrealistic. So, what exactly will the jury members be evaluating, and on what basis will the award be given?

In November 2025, just one month after the shortlist announcement, the winner of the BRICS Literary Prize will be announced in Moscow. Kuznetsov referred to this part as an “element of showmanship.” “The best BRICS author does not mean they are the best author of all time and peoples. It is rather a competitive element, which is acceptable in a playful form,” said the head of the prize secretariat.

During the press conference, Dmitry Kuznetsov mentioned the Nobel Prize several times. He stated that it is awarded only to those who reflect “Western values” in their works. In his view, the BRICS Literary Prize could become a kind of alternative. A bold claim. But for now, let us first look at the longlist.

Since we are talking about major prizes, it is worth recalling the prize funds. For example, in 2023 and 2024, Nobel Prize laureates in Literature received 11 million Swedish kronor, roughly 1.1 million US dollars. Meanwhile, the winner of the Goncourt Prize receives a symbolic 10 euros. From this perspective, the BRICS Literary Prize truly falls in the middle. Alexander Ostroverkh-Kvanchiani, director general of the Eurasian Book Agency, proposed awarding the prize winner a “modest” cash prize of 1 million rubles. He emphasised that this is a fairly small amount for this prize. Compared to the Goncourt, however, it is quite a decent reward. But, for example, Russian literary prizes such as the Big Book and Yasnaya Polyana award their main category winners 3 million rubles each.

The other participants at the press conference did not say anything particularly substantial. Mostly, they spoke about how great it is that such a prize has been established and how it will unite different cultures. Egyptian writer and parliamentarian Doha Mustafa Assi said the BRICS Literary Prize will become “the voice of the Global South.” Dr Shoaib Khan, a member of the prize organising committee from India and president of the educational and cultural society ALFAAZ, shared how he avidly read translations of Russian classics before the collapse of the USSR. He also expressed hope that he will now be able to discover “the contemporary Russian soul.” This, despite the fact that just six months ago, a translation residency was held at the Peredelkino House of Creativity, where a collection of Anna Shipilova’s stories, Soon Moscow, was translated into Hindi.

The member of the prize organising committee from Iran and head of the Cultural Centre at the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Iran in Russia, Masoud Ahmadvand, began his speech by condemning the actions of Israel and the United States, despite the moderator’s initial request to speak only on the topic of the prize. He then stated that “pens can be mightier than swords,” emphasising the need to write more and fight less. The committee member from the UAE and political science professor, Dr Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, reminded the audience that the United Arab Emirates has a Ministry of Tolerance and Coexistence, and called on everyone to be tolerant.

Ekaterina Petrova is a literary reviewer for Realnoe Vremya online newspaper and the host of the Telegram channel Poppy Seed Buns (Bulochki s Makom).