How mirrors in Soviet paintings transformed into selfies

Art historian Kirill Svetlyakov explained how the image of the narcissistic hero was born in Soviet culture — and lives on to this day

A lecture by Kirill Svetlyakov — art historian, curator at the Tretyakov Gallery, and author of the book Soviet Culture: From the Grand Style to the First Raves —was held at the National Library of the Republic of Tatarstan. As part of the Garazhki MIFa series, he spoke about how, in the 1970s, the mirror displaced the window, the wardrobe became a portal, and artists became hostages to reflections. Why the narcissistic hero became the central figure of the era — and how he survived in virtual reality before the internet.

From a childhood obsession with the zoo to a book on Soviet culture

The book Soviet Culture: From the Grand Style to the First Raves was not born in the archives. Not in tedious lists of exhibitions, and not in academic dust. Kirill Svetlyakov warned from the outset: “This is not quite an academic study.” Academic studies, according to Svetlyakov, are when “two-thirds of a page is taken up by a footnote, and the rest is a quotation.” Such a book is hard to read. Such a book is rarely reopened. And if the author suddenly draws their own conclusions, academic peers may immediately ask: “What are you basing this on?” And so begins the dance around the question “are you absolutely sure?”, especially when it comes to a doctoral dissertation. To avoid doubt, many deliberately narrow their topic to a microscopic scale.

Soviet Culture: From the Grand Style to the First Raves was written based on lectures that Svetlyakov delivered on the portal Stradarium — the very one that emerged from Suffering Middle Ages. The medievalists expanded the boundaries, and the expansion into the 20th century began. There, Svetlyakov gave a series of seven lectures titled A Good Bad Man. “I perceive Soviet culture anthropologically, as material for describing the human being of the second half of the 20th century and everything that happened to them. And not only the Soviet person, but the person of industrial culture in general,” Svetlyakov explained. This is the essence of the book: a person caught between a vanishing traditional world and an advancing industrial one.

When exactly did traditional culture disappear? Not in the 1960s. And not a decade earlier. According to Svetlyakov, it happened already at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Peasants stopped making things with their hands and began to buy them. Their hands were freed. And they turned to painting. This is how naïve art emerged. Not folk art, but post-folk art. A product not of traditional culture, but of its absence.

This was not merely a historical shift. It was a new consciousness. A consciousness of culture. Because “traditional culture” is, in itself, a vague concept. Is it academicism? Peasant art? Or simply everything that existed before factories? And if the factory already signifies industry, then the person of the 20th century is an industrial person. And the Soviet person is just one of their incarnations.

Svetlyakov approached this as a study of the human being, not of art as such. Art is a mirror. What matters is who is looking into it. But how did Svetlyakov himself come to this perspective? He explained — and began with a crocodile: “Why did I become an art historian? Because I love crocodiles.” The terrarium at the Moscow Zoo was his first object of fascination. He would stand by the glass for long stretches. Watching, connecting. Then the terrarium was closed. For fifteen years. The object disappeared. Svetlyakov began collecting images of crocodiles. Searching for the best one. “Art often captures and reflects what is vanishing,” the art historian added. The crocodile vanished. What remained was visual memory.

As a child, Kirill Svetlyakov joined the Young Biologists’ Club at the zoo. It seemed logical: if you love crocodiles — become a biologist. But it didn’t work out. “We kept observation journals. And the club was supervised by serious people. They read my descriptions and said: ‘You know, you’re definitely not a biologist. We don’t know what this is exactly, but for you, the animal is some kind of image. You describe it like a picture. We don’t know what that is, but it’s not what we do,’” Svetlyakov recalled.

An image. Not behavior, not habitat. A form. Svetlyakov stayed in the club, but realised that his interest did not lie in biology. He meditated on the image. Searched for the perfect depiction. And he found it. It was Vladimir Mayakovsky’s book Each Page a Beast, a Bird, or a Beauty, with illustrations by Vladimir Gusev. In it, the crocodile was depicted through text.

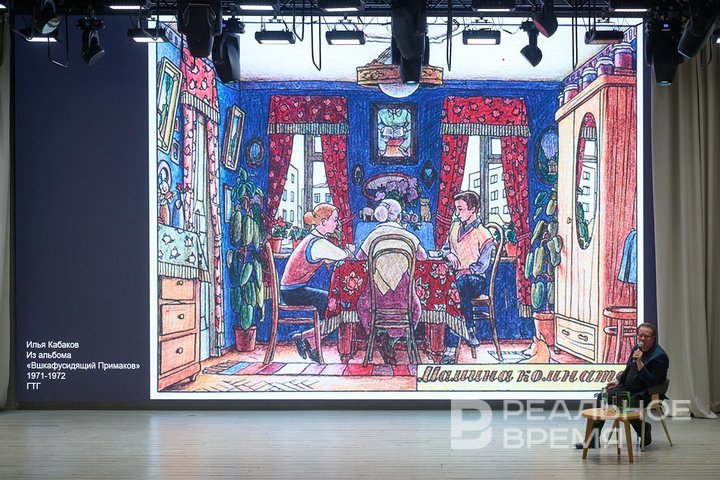

Then there was water. Svetlyakov learned to swim. He played at being a crocodile. He learned to be an image. Then came the Pushkin Museum, the early 1990s. Lectures. Modernisms. And — Marina Bessonova. She spoke about Ilya Kabakov. About the album Vshkafusidyashchiy Primakov. “There was once a boy who loved to sit in a wardrobe. He sits in the wardrobe. He draws the wardrobe. Then the boy flew out of the wardrobe and began to travel across all worlds,” the art historian described Kabakov's illustrations in the album Vshkafusidyashchiy Primakov.

Bessonova showed pictures. In one, we are looking at the wardrobe from the outside. In the next, we are already inside. “And then the door shuts, and we can’t see anything anymore, we just hear,” Svetlyakov added. This is conceptualism. Entering the image, losing sight, heightening the sense of hearing. The shift from image to imagination. Svetlyakov understood everything without needing an explanation.

How the wardrobe became a portal, the mirror — a stage, and the artist — a reflection

When we think of the 1970s, images of small kitchens, buzzing televisions, and albums with faux-leather covers come to mind. But in Soviet art of that time, there were far more reflections than light. Literally. Repeating motifs of mirrors, wardrobes, and windows became themes that strangely seeped into animation, painting, and photography. They were not dependent on style, status, or affiliation with the underground or official art. The images seemed to be born from a collective subconscious.

Kirill Svetlyakov said: “When you start immersing yourself in an era, strange things happen.” One of these strange occurrences is the animated film The Wardrobe by Andrei Khrzhanovsky. Made at a studio and approved by the art council, it began as a domestic story about a man who bought a wardrobe. “And then this wardrobe almost ate him," Svetlyakov said. The protagonist settles inside the wardrobe, brings things there, and disappears. The wardrobe becomes a metaphor — an object that not only occupies space but also takes control of the mind. As if heavy furniture becomes a portal.

“The animation is remarkable because it’s done in the style of René Magritte," Svetlyakov explained. There was a painting with the sky. But it wasn't a window — it was a painting. The protagonist hangs it inside the wardrobe. And immediately, in this space, a mirror, a window, and a mirrored wardrobe appear. “Like a portal to another dimension," the speaker added.

A similar story appears in Ilya Kabakov’s album Vshkafusidyashchiy Primakov. Again, the object and the person merge. The entrance into a confined space — and disappearance. Absorption. But the strangest part is not this. It’s that the same motifs appeared in different points of culture — among both official and unofficial artists. Wardrobes, mirrors, reflections, vanishing figures, split identities. “When you look at it, there's a sense that there are obsessive images. Or, as Carl Gustav Jung said, archetypes," Svetlyakov explained.

He provided examples. Rashid Asaev — a fairly official artist. In his work Interior in Senegé, the artist sits in an artists' house and dissolves into the empty canvas. He doesn’t paint — he enters a trance, disappearing. A similar effect is found with the Moscow group Gnezdo. They performed a piece where the artists literally fix their gaze on the canvas. The performance was a one-hour session of hypnotising the canvas, waiting for a masterpiece to appear on it. The painting transforms into a mirror. Or a portal. Or a trap.

On Ksenia Nechitaylo’s canvas My Brother Came Back from the Army. Mirror, there’s a scene with a mirrored wardrobe. A simple plot, but the mirror cracks reality. One world shatters. Doubles appear. “As if one world is splitting into several worlds," Svetlyakov said. He emphasised that these images appeared simultaneously among artists who didn’t even know each other. Among those who stayed in the Artists' House, and those who created animated films. Among those working in the genre of conceptual performance and those painting still lifes with mirrors. “And then, sometimes, there’s the feeling that it’s like one super-artist or one theme, which is realised in different ways," Svetlyakov explained.

The mirror motif, according to him, becomes more important than the window motif. “Mirrors reflect interiors, and this interior is projected onto the window. And in this way, this strange magical portal arises," said the art historian. On one side of the scale is Yuri Pimenov with his Spring Window, where you can see: reality is outside the window. On the other side is Alexander Petrov and his painting Mosfilm. It also seems to be a window, but behind it — decorations. Falsehood. Illusion. The artist in this painting is not a spectator, but a creator of illusions. “With Pimenov, we believe that reality lies outside the window. But with Petrov, instead of reality, there is a simulacrum. He questions his own sense of reality. It’s unsettled," Svetlyakov noted.

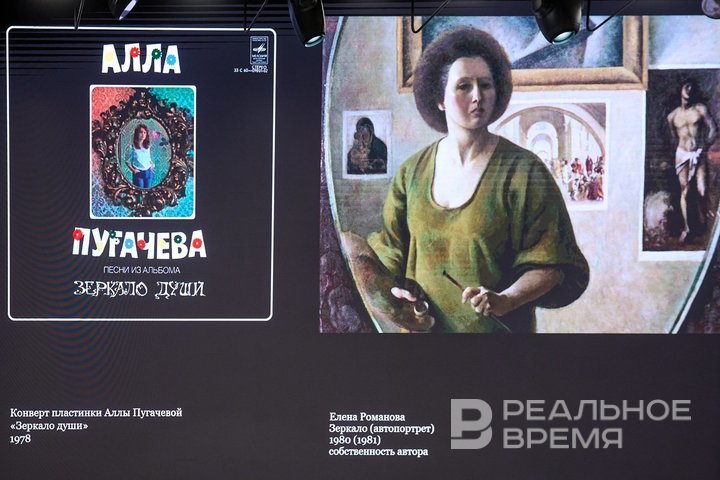

In these motifs, there is no longer an external world. Only the internal one. And it’s not just internal — it is reflected, distorted, drowned in the mirror, in the canvas, in the wardrobe. The artist Elena Romanova painted a self-portrait while sitting opposite a mirrored wardrobe. But in this reflection, it’s not just her. Reproductions hang around her. In them, there are echoes: Raphael’s arch and the cut of a sweater. The modeling of the face — and the face of Saint Sebastian. “She literally immerses and dissolves herself in this imagined space of culture. And not just any culture, but global culture,” Svetlyakov added. A similar image appears on the cover of Alla Pugacheva’s album Mirror of the Soul. “The theme of the mirror is obsessive,” the speaker remarked.

And it becomes especially obsessive when linked with another character — the narcissist. This is a figure that emerges precisely in the 1970s. He doesn’t just look into the mirror — he sees himself in it, but not directly. “You remember Yury Antonov’s song *‘I look into you, like into a mirror, until I’m dizzy and see my love in it, and I think about her,’” Svetlyakov quoted. “He looks into the mirror, but sees his love in it. So, the lover becomes the mirror. It’s a mirror for self-admiration,” the art historian explained.

Thus, a new type of hero is born. He looks at another to see himself. He is not searching for an object; he is searching for a reflection. And the mirror becomes a tool to see what he wants to see. This type of hero requires the constant presence of a double. And this is where the connection to today begins. “Modern museum visitors come to the museum and take selfies in front of masterpieces. And how is that different from the story depicted in Romanova’s self-portrait?! Practically nothing,” Svetlyakov said.

Instead of a mirror — there's a phone. “It serves as the same mirror. And the perception of everything through oneself — I'm in the background, I’m looking at myself in the background. I am also my double, my avatar, which exists in a second reality. And I feed it with my life," explained Kirill Svetlyakov. The same patterns as those of the artists of the 1970s: dissolving in the reflection, fixing one's version, duplicating.

And these are not random coincidences. “The situation of similar, recurring motifs is determined by drives, cultural context, and the feelings of people during a certain period," explained Svetlyakov. Artists, he said, sometimes feel offended when they are told that their works “look like this, that, and the other.” But this is precisely the work of the art historian: to discover patterns, recurring structures, and common themes.

“The artist protects their individuality. And they don’t want anyone to intrude on it. But the art historian is precisely the one who intrudes," Svetlyakov said. And what they discover is that in culture, just like in a wardrobe, everything is interconnected. One reflects the other. One absorbs the other. And disappearing inside is just a matter of time.

Ekaterina Petrova — a literary columnist for Realnoe Vremya online newspaper, the author of the Telegram channel Bulochki s Makom (Buns with Poppy Seeds).