Everything has already been written!

Why secondary is not always bad and how literary originality actually works

What is originality in the era of endless rewrites, references and literary franchises? Today, a writer can easily be inspired by a myth, rewrite a classic in a new way or integrate into someone else's universe — and all this is considered creativity. But where is the line between a quote and plagiarism, a dialogue with the canon and secondary? And how can we understand where influence ends and a copy begins? Literature has always fed itself — the only question is how elegantly this is done. Representatives of the book industry discussed the boundaries between the original and the secondary in literature at a discussion at the N.A. Nekrasov Library in Moscow.

Not “about what” but «how”

They say that everything in literature has already been written — all that remains is to put the characters in their places and choose a new font. Back in the 19th century, the French critic Georges Polti came up with Thirty-Six Dramatic Situation, from theft to self-sacrifice. Christopher Booker in his book Seven Basic Plots claimed that any novel, play or blockbuster can be reduced to one of the eternal scenarios: “from poverty to wealth,” “victory over the monster,” “journey and return” and so on. In the Russian tradition, Vladimir Propp disassembled the folk tale into 31 functions of the characters, which are repeated like parts in a Lego set. And although almost a hundred years have passed since then, writers are still assembling their stories from this limited construction set.

But what can be considered new if everything has already been invented? “The question is not ‘about what’ but ‘how.’ Each new generation of writers invents its own ‘how.’ Sometimes it turns out to be a bicycle, and sometimes something new, at least conceptually different. And new readers are growing up,” said Anastasia Shevchenko, book reviewer, editor, and producer of book projects at the Alpina. Proza publishing house. She also added that critics will still write that something similar has already been done, and readers will admire and ask for more texts from the author.

Literary critic and editor-in-chief of original projects at Yandex Books Ksenia Gritsenko does not agree that literature goes in circles. “We live in a world in which everything changes, everything is updated. And any text is a reaction to the current, so it cannot be the same all the time, and it is at this juncture that novelty is born,” Gritsenko said.

Another logical question that follows from the topic of originality in literature: who exactly needs this originality? For example, in fan fiction, this is a completely unnecessary aspect. Fan fiction is the most honest form of secondary literature that does not pretend to be original. These are texts born out of love for other texts: fans take other people's worlds, heroes and conflicts and rewrite them the way they want — correct the “mistakes” of the canon, give lovers a happy ending or transfer Hogwarts wizards to the Amazon office. On the one hand, fan fiction seems to destroy the boundary between the author and the reader, erases the aura of “high” literature and turns it into a game. On the other hand, it shows that nothing in culture is born from a vacuum. Even the greatest novels were built on the shoulders of their predecessors. In this sense, fan fiction simply makes inheritance visible — and joyful.

“If you slightly rearranged the original notes, but the tune turned out to be exactly the same, and preferably also the arrangement and sound, then you're great. People want to read a continuation of a well-known universe, to meet their favourite characters again. People want to read something in a familiar genre, but with a new variation and a new twist,” said journalist and HSE teacher Yuri Saprykin.

Repeating plots in literature are not a dead end, but a palimpsest: with each new reading of an old story, other meanings appear on its surface. Romeo and Juliet in the 17th century is a drama about rebellious children, in the 20th — a parable about the impossibility of love in the system, in the 21st — a meme, a musical number, a video on TikTok. Stories live on as they are retold, and each time they adapt to new fears, dreams, and language. So the ancient myth of Gilgamesh, after thousands of years, can be resurrected in a graphic novel about an immortal cyborg, and a Greek tragedy in a rom-com about office clerks. Repetition is not a copy, but a method: a way to ask an important question again and hear a different answer.

What the author was hinting at

Literature loves to have dialogues, usually with great authors who have already died: some books quote others, hide hints, encrypt meanings — and sometimes resemble a game of “guess where this phrase is from.” Sometimes it is obvious: the hero opens a volume of Proust argues with Kafka. But more often — more subtly and latently. I saw a banal scene with an apple — and this is already Genesis, and Twilight, and Paradise Lost. The problem is that the reader does not always notice when the text “winks” at him in someone else's voice. The reference eludes if you have not read the original source, and then the halftone disappears. This makes literature a little elitist and insidious.

“If the text is oversaturated with quotes, you may not recognize them, but you still feel that they are there. Here the question arises: what did the author want to say or do? If he encrypted a literary game in the text, which is the meaning of the work, then, excuse me, some then finish reading the book without resting with it. But it happens that the author made a multi-layered work with many allusions, and the reader may not see them at all, but enjoy reading,” Saprykin explained.

Pushkin seems to have been the first in Russian literature to turn quotations into a form of friendly code: his poems are full of “greetings” — sometimes to Boratynsky, sometimes to Vyazemsky, sometimes to Derzhavin. He didn't just quote — he played, reassembling other people's lines, like cubes, in a new order. In Eugene Onegin there are references to Byron, in Count Nulin there is a joke about classicism. Even in The Captain's Daughter there are shadows of Karamzin and Radishchev's pathos. At the same time, reading his works now and without delving into all these “greetings,” the reader gets pleasure and enjoys the plot.”This game, understandable for Pushkin's circle, is no longer understandable for us,” added Yuri Saprykin.

For publishers, secondary nature can become a good marketing tool. It is much easier to “sell” a book if you can quickly explain what it is like: “it’s like Harry Potter, but in a cyberpunk world” or “Stephen King meets Dostoevsky.” The reader does not have to guess — he immediately understands what emotional zone he is being led to. There is no deception in such descriptions: it is a kind of navigation through a cultural landscape, where new stories grow from old roots.

“As a publisher and as a person who sells books at fairs, in my recommendations to readers I rely largely on what exactly new books have in common with what is recorded in the reader’s subcortex. I say: if you like this, then this will do too. I try to build an associative series so that it is easier for a person to navigate the book space. I do the same as a reviewer and as a critic,” said Anastasia Shevchenko.

Good literature works on all levels — for those who recognize a hint of Hamlet in the hero, and for those who are simply reading about a guy who thinks too much. The reader does not need to be a walking encyclopaedia to enjoy the book: references are not an exam, but a bonus, like an Easter egg in a film. You can notice them, or you can pass by and still enjoy them.

“The text has a key property — to be friendly or not to be friendly. With friendly texts, everything is generally clear, it works for any reader. With unfriendly texts, it is much more difficult. At the same time, we have a certain tendency towards masochism. Sometimes we want to experience this unfriendliness and, if compared with an abusive relationship, prove to ourselves that “with me this text will be different”, I will understand it, intellectually I am at the level of the author, and maybe even higher. This is also a completely normal reader's scenario,” noted Ksenia Gritsienko.

Plagiarism or reference?

Speaking about references and borrowings, we cannot avoid the topic of plagiarism. Sometimes borrowings are truly blatant. For example, Alexandre Dumas in The Three Musketeers relied on the Memoirs of Monsieur d'Artagnan by Gatien de Courtil de Sandras, borrowing not only the plot but also the characters. Modern authors also face accusations of plagiarism. For example, in 2006, Dan Brown was accused of borrowing ideas for The Da Vinci Code from the book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail by Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh.

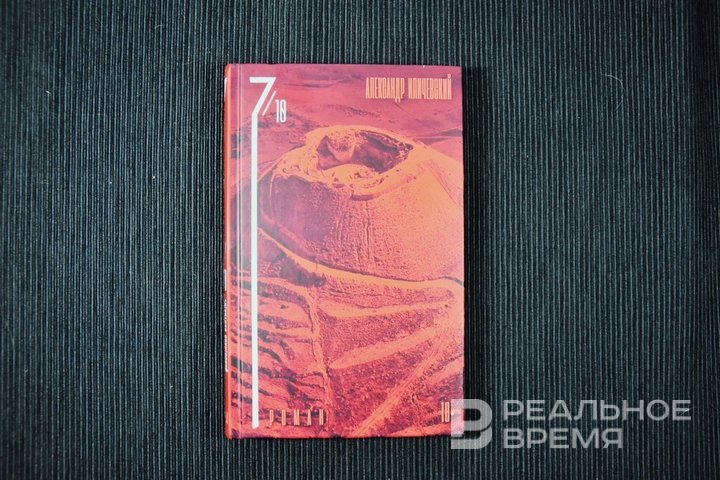

At the beginning of 2025, the Russian literary world was rocked by a scandal: extensive borrowings from other people's texts were discovered in Alexander Ilichevsky's novel 7 October. Israeli journalist Alla Gavrilova accused the writer of using fragments of her report without indicating the author. It was later revealed that the book also contained excerpts from the story Adventures in the Desert by cosmophysicist Vladimir Murzin and the works of Andrey Platonov. Initially, Ilichevsky denied the accusations, stating that “literature cannot exist without the exchange of meanings, words, letters.” However, under public pressure, he admitted his mistake, apologized, and promised to make changes to the text. Alpina. Proza publishing house confiscated and destroyed the paper edition of the novel, and the corresponding edits were made to the electronic version.

Plagiarism is always on the edge: where does inspiration end and theft begin? Especially in a world where “everything has already been written.”

“An important criterion for borrowing: did the author want us to know that this was borrowing, or did he not? If you copy someone else’s journalistic text, passing it off as what the hero has written or thought of, the writer probably wouldn’t really want anyone to recognize it. There is no collage, no technique, no quotation in this. There is no goal other than to fill two pages with a plausible text. And if the author wanted this borrowing to be unraveled, then he is a good man,” noted Yuri Saprykin.

Secondary does not always mean banal, and primary does not necessarily mean great. Literature lives on references, dialogues, borrowings and bold reassembles. The main thing is not to hide inspiration under someone else's name, but to turn it into something of your own. Because behind any “already been” there is always a chance to say: “but now — differently.”

Ekaterina Petrova is a book reviewer for the online newspaper Realnoe Vremya and the author of Buns with Poppy Seeds Telegram channel.