Scarcity, standardisation, struggle for style, and endless compromises: fashion in the USSR

Researcher Yulia Papushina explores how the Soviet fashion industry operated despite svere restrictions

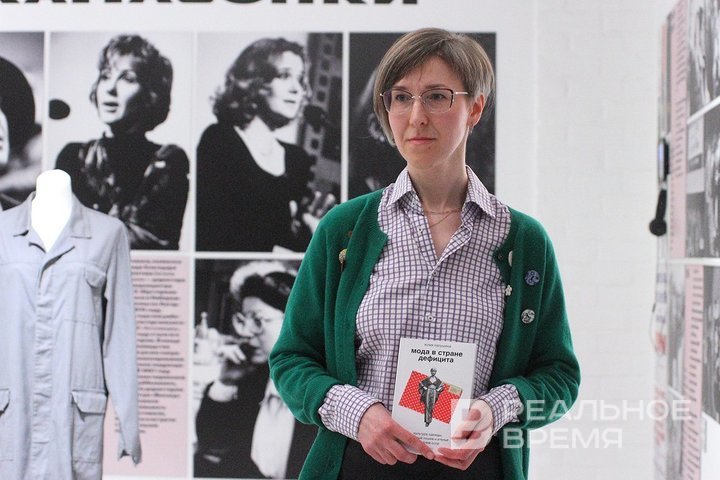

Soviet fashion was mass-produced, but hardly universal. Fabric shortages, a lack of choice, the struggle to find larger sizes, and the attempt to keep up with Western trends through homemade outfits — this was the reality rarely discussed. A recent presentation of sociologist Yulia Papushina’s book Fashion in the Land of Shortages at the Smena Centre for Contemporary Culture was an occasion to recall what really happened and why Soviet fashion seems to have been erased from history today.

How the USSR shaped taste

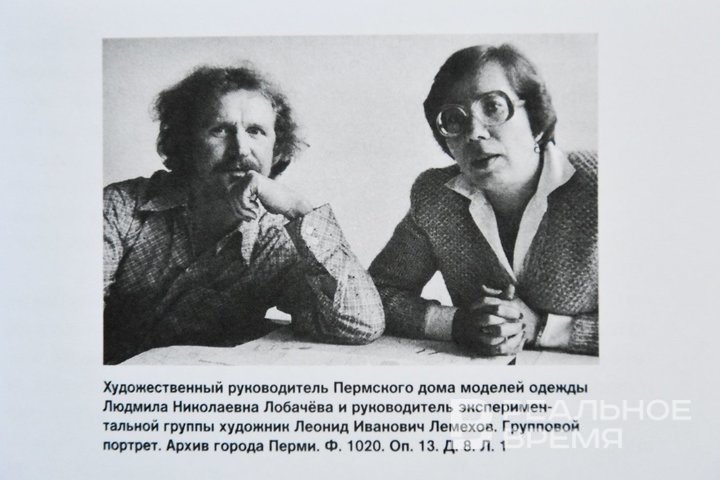

The Soviet Union dictated not only political discourse but also ideals of beauty, clothing, and personal appearance. Control extended to every aspect of life — including fashion. “Clothing is literally the closest thing to the body. It’s part of everyday life,” recalled Yulia Papushina, citing former designer and artistic director of the Perm Fashion House, Leonid Lemekhov. The cultivation of taste was embedded in the state education system, ideology, and clothing itself.

Yet, despite strict regulations, people found ways to look stylish. Soviet designers and artists created pieces that rivaled Western fashion, even within the constraints of what was permitted. “One of the ideas behind this book was to show that people weren’t walking around in potato sacks — they knew how to look good,” Papushina explained. Soviet fashion designers formed a distinct professional community, made up of highly educated specialists. “Their talent, their potential, their creativity were often underutilised,” the researcher noted. A vast creative force remained unrealised, stifled by the rigid system.

Soviet fashion was highly regulated. Anyone wishing to work in the industry had to undergo formal education. There were private seamstresses, they were not recognised at an industrial level.The path into Soviet fashion always began with education, which offered two options: vocational training or higher education. There were two options: specialised secondary or higher education. Those who started with technical schools (now colleges) could first become tailors or high-class seamstresses. It was already possible to complete professional training at school. In the Perm House of Models, there were cases when people came with seamstress qualifications, gradually raised their level, received higher education in absentia, became fashion designers, group leaders, and then artistic directors.

If a person chose to pursue higher education directly, there were two paths. The first was to enroll in specialised universities for fashion designers. “There were very few universities in the Soviet Union that specifically trained designers who created clothing,” Papushina noted. In the RSFSR, they could be counted on one hand: the Mukhina School in Leningrad (now the Stieglitz Academy) and the Moscow Textile Institute (now part of Kosygin University). The second path was to obtain a technical education and become a clothing constructor. Specialists in this field were trained not only in the capital but also in several regional cities. From the 1960s onwards, universities with programs in clothing construction began to appear. In regional fashion houses, graduates with these degrees were also appointed as designers.

While receiving their education, Soviet fashion designers absorbed the strict framework of state fashion policy. “The state very clearly shaped the mental map of future designers,” noted Yulia Papushina. They knew who they were creating clothes for, what principles they had to follow, and what was permitted or forbidden. Even the most talented designers worked within ideological boundaries. “Even Slava Zaytsev was well aware of the limits of what was allowed,” the sociologist said. It was only in the mid-1970s that he finally stepped beyond these boundaries, leaving the All-Union House of Fashion and moving to the Moscow Fashion House.

The Soviet system did not require total control over the streets. By the time clothing reached the stores, it already conformed to the “correct” taste. “When we talk about the control of taste, we shouldn’t imagine strange people running around shouting: ‘Take that off immediately!’” Papushina remarked.

Moscow knows best

At the top of the Soviet fashion industry pyramid there were two key institutions — the All-Union House of Fashion and the All-Union Institute of Assortment of Light Industry Products and Clothing Culture (VIALLEGPROM). These were the entities that decided what Soviet citizens would wear in the coming seasons. It was here that the elite of Soviet fashion design gathered to develop the so-called “creative collections.” This was the prospective design group — a structure that set the direction for Soviet fashion. Every other Fashion House in the country worked based on these ideas.

The next level of the system was the Leningrad House of Fashion, which had a unique history rooted in pre-revolutionary fashion traditions and was known for its high-quality craftsmanship. Another major fashion hub was the network of Republican Fashion Houses. Riga and Tallinn stood out in particular — at the crossroads of Western and Soviet cultural influences, they published fashion magazines and enjoyed popularity on par with Moscow’s institutions. The Kyiv and Lviv Fashion Houses also held high status, offering elegant and modern silhouettes.

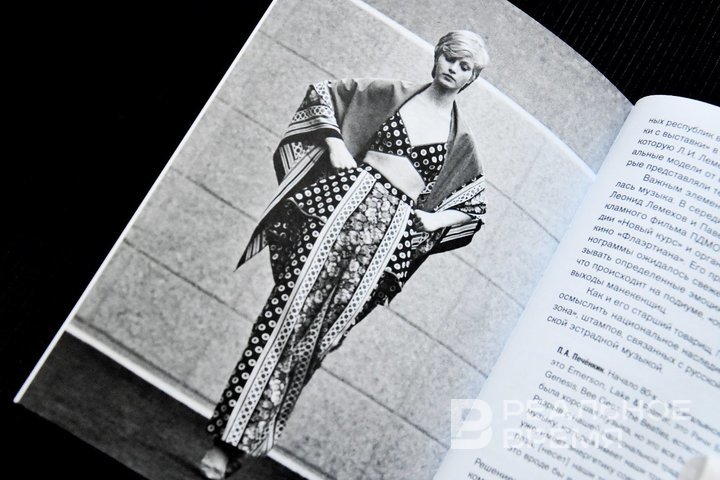

Regional fashion houses in Central Asia faced greater challenges. While they actively incorporated local decorative and applied arts into their designs, their influence remained limited — Western fashion trends primarily flowed through the Baltic states. At the bottom of the fashion hierarchy there were the regional fashion houses, mostly located in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). These houses were established in major industrial centers with a well-developed textile industry, where there was a need to merge design thinking with production capabilities.

The hierarchy was rigid. Moscow controlled the process, set the direction, and communicated it to lower-tier institutions through methodological guidelines and meetings. Regional fashion houses showcased their collections at these gatherings, receiving feedback from their senior colleagues. This was their only opportunity to break through to the next level and make a name for themselves.

How to get to Leipzig

International fashion exhibitions were not just glamorous events; they also served as a tool of political propaganda. The Soviet delegation was expected to present the country in a way that portrayed it as a “united family” of 15 republics. This meant that the selection of participants was highly meticulous, and the showcase itself had to emphasise unity and cohesion.

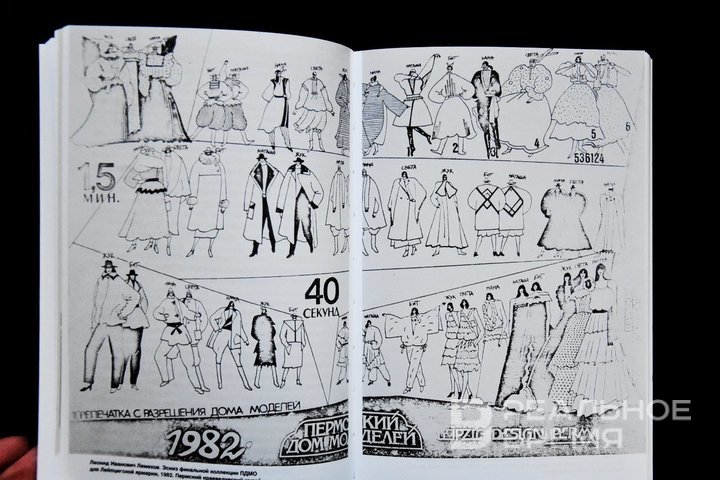

In 1982, the Perm House of Models was unexpectedly invited to the Leipzig Fair. An ordinary regional centre, which had never participated in such large-scale events, got a chance to represent the USSR on the international stage. This was preceded by one important event: in 1978, Leonid Lemekhov, a graduate of the Mukhinsky College, took the post of chief artistic director. He changed the approach to modeling and introduced conceptualisation into it.

Lemekhov dreamed of showing the Urals in Leipzig — gray mountains, harsh landscapes, and Bazhov's fabulous aesthetics. However, this idea did not meet the party's agenda. In 1982, the USSR celebrated its 60th anniversary, and the task of fashion designers was not to demonstrate regional identity, but the unity of the country. Lemekhov had to rethink the concept: he designed stylised costumes that reflected the traditions of all 15 republics, which fit into the ideological course. The show was divided into two parts. In the first — there are theatrical images that represented the republics of the Soviet Union. In the second, there is a classic fashion show with a demonstration of products, gradually moving from outerwear to evening dresses. This principle was considered logical for Soviet fashion shows.

Lemekhov did not complain. He understood the task at hand and approached it in the only way possible — by merging his creative vision with the Party’s directives. His efforts paid off: the Perm Fashion House made a name for itself, a rare case where an individual’s talent managed to break through the rigid system.

The story of the Perm Fashion House demonstrates that even within a strictly regulated system, there was room for creativity. While the Soviet fashion industry remained a tool of political influence, talented designers still found loopholes for self-expression. They took part in international exhibitions, adapted to official requirements, yet still managed to leave their mark on history.

Traditions — yes, industries — no

Soviet fashion was never about individuality. It wasn’t even about the consumer. Unlike the global fashion industry, which revolved around demand and customer preferences, everything in the USSR was dictated from above. Fashion houses didn’t create collections for people—they designed them for factories. It was a closed-loop system where the end consumer was left out of the equation. And this became the fundamental problem that Soviet fashion never managed to overcome. “The clients of fashion houses were factories. The peculiarity of Soviet fashion was that the end consumer played little role in it. The Soviet citizen was given what was deemed proper, tasteful, and appropriate," explained Yulia Papushina.

Factories didn’t evaluate designs based on style or relevance but purely from the standpoint of production efficiency. If a garment was too complex or costly to manufacture, it was immediately rejected. “Remove all the tabs, remove all the pockets” — this kind of dialogue between designers and factories was standard practice. But even if a design managed to pass through all the bureaucratic hurdles, it didn’t mean people could simply walk into a store and buy it. Scarcity permeated the entire Soviet fashion system. “First, a person might have liked something different from what was available in stores. Second, the system failed to acknowledge that fashion cannot exist without mass production. If we can't mass-produce fashion, problems arise. We may have brilliant one-off pieces, but there is no proper industry with a consistent quality standard," explained Papushina.

In the end, fashion in the USSR became something ephemeral. Fashion magazines showcased beautiful sketches that never made it into mass production. People resorted to sewing their own clothes, using handmade patterns, because stores only offered dull, factory-made designs. Those lucky enough to travel abroad or acquire imported clothing became the true bearers of fashion — not the one that was created in institutes.

The Soviet fashion industry never managed to establish a sustainable working model. Unlike in the West, where fashion evolved in response to consumer demand, in the USSR, it was dictated by bureaucratic decisions. This led to a paradoxical situation: on the one hand, talented designers were creating unique pieces; on the other, the mass market remained flooded with monotonous, poorly made clothing.

The problems of Soviet fashion didn’t disappear after the USSR collapsed. “At a presentation in St. Petersburg, someone asked whether our struggles stem from a lack of design traditions. But we do have a tradition — the problem is, we don’t have an industry. The tradition of creating clothing and having a functioning fashion industry are two different things," said Papushina. It is this very absence of an industry that continues to hinder Russian fashion from reaching the global stage.

Trying to keep up with the youth

The concept of youth fashion emerged in the socialist bloc only in the 1960s, and even then, it progressed slowly and with great difficulty — almost crawling forward. In the magazine Fashion of Socialist Countries, the first attempts at designing youth-oriented clothing can only be found in 1965, while such garments only began appearing on the mass market in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Why did it take so long?

Fashion in the USSR was developed centrally, and until the 1960s, young people simply did not exist as a distinct consumer category. It was only through the Commission on Clothing Culture of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance in Prague that designers across the socialist bloc began discussing common trends. This led to the first youth fashion designs appearing in Soviet fashion magazines — but at that stage, they remained more of a declaration than a reality.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Soviet youth no longer looked to domestic runways for inspiration. “By then, Soviet people had access to Western films, even if they were censored, and could read magazines from Eastern European countries," noted Yulia Papushina. In a climate of scarcity, Soviet teenagers preferred to sew their own clothes. A sociological study conducted by the All-Union House of Fashion showed that young consumers had little interest in Soviet fashion shows but would be willing to pay more for trendy items if they were produced in limited editions.

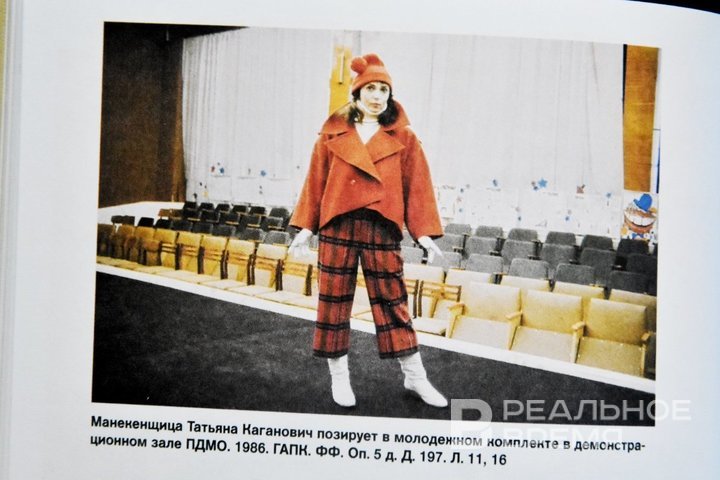

The Perm House of Fashion attempted to address this issue by creating a “youth brigade”, a special team of designers focused on developing fashion for younger audiences. These garments were produced in small batches and sold at TSUM. However, factories were reluctant to support the initiative. “The trade administration decided to open a fashion store with youth clothing, but factories failed to supply the assortment and disrupted the project," stated one document from that time.

Far from ordinary women

Soviet fashion positioned itself in opposition to Western fashion, claiming to be more democratic. In theory, it was designed for people of all ages and sizes. In reality, things were different. Consumers demanded larger sizes, factories requested patterns to accommodate them, and fashion houses designed clothing for bigger men and women. Catalogs even featured specialised models showcasing these garments. But on the runways, such models were almost nonexistent.

“There were very few of them at shows because they simply didn’t look good on the catwalk," explained Yulia Papushina. Fashion shows were spectacles, and striking silhouettes looked best on tall, slender figures. Soviet fashion models were over 170 cm tall and no larger than size 46. Compared to today’s standards, this wasn’t extreme, but even then, an unspoken divide existed — one kind of clothing was made for the mass consumer, while something entirely different was presented on the runway.

Modeling was not a highly paid profession, but it had other perks: working among creative people, access to clothing unavailable in stores, and the chance to hear candid conversations about politics and life. “Imagine someone putting a tunic on you, and its hem detaches to turn it into a dress. That’s cool, isn’t it? Incredible!” said Yulia Papushina. It was in such designs that the true value of the industry lay, even if they didn’t always reach the masses.

Soviet fashion ended as abruptly as the era itself — suddenly, yet with a lingering echo. “You know, there's a Latin saying: ‘Thus passes the glory of the world.’ That phrase kept haunting me as I conducted interviews," said the researcher, reflecting on the people from the Soviet fashion industry while collecting material for her book. But an ending does not always mean oblivion. At least for the author of Fashion in the Land of Shortages, this moment represents a second chance: “This is my only attempt and my only opportunity to restore the names and memories of people whom history has somehow forgotten.”

These people are still alive. They work, teach, and create. Their contribution to Soviet fashion is no less significant than that of Vyacheslav Zaitsev or other recognised masters. After all, fashion wasn’t made only in Moscow and Leningrad. It was also created in Perm, Novosibirsk, Kazan, and hundreds of other cities, where designers on runways and in sewing workshops shaped the style of millions.

Ekaterina Petrova — a literary columnist for Realnoe Vremya online newspaper, the author of the telegram channel Buns with Poppy Seeds.