Buried Stories

The Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tatarstan has presented three new books on archeology about the Srostkin culture in the south of Western Siberia, about the Upper Irtysh region and the Altai steppe, and about the Uyghur Khaganate

Time blurs boundaries. Nomadic peoples are leaving, cities are disappearing, and states are replacing each other. But the land keeps a memory. Archaeologists find traces of ancient civilisations. Mounds, hillforts, burial grounds — these silent monuments depict the fate of people who lived in the 8-12th centuries. On 3 March, the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tatarstan presented three books on archaeological finds in the south of Western Siberia, in the Upper Irtysh region, in the Altai steppes and in Mongolia within the framework of the conference “Archeology of Medieval Cities of Steppe Eurasia”.

When artifacts speak louder than words

The discovery, systematisation and analysis of archaeological sites is the result of many years of work by scientists. The book “Monuments of Srostkin culture in the south of Western Siberia” by V.V. Gorbunov and A.A. Tishkin collects data that can rewrite the idea of the ethnocultural processes of medieval Eurasia. The researchers provide a detailed overview of archaeological sites, their chronology, cultural features, and historical context. If earlier the Srostkin culture remained in the shadow of more well-known archaeological phenomena, such as the Kimek or Karluk worlds, now it is becoming an important element of the puzzle that puts together a picture of the life of the Turkic peoples of medieval Siberia.

The discovery of the Srostkin culture is the result of almost two centuries of archaeological research. The first excavations in these places were carried out back in the 19th century, but it was only during the Soviet era that scientists were able to systematise knowledge about the monuments associated with this population. Today, more than 200 archaeological sites have been explored, including 20 settlements, 5 hillforts, 120 burial mounds and 18 underground cemeteries. A total of 778 graves have been studied.

Mounds are one of the most valuable sources of information about the past. Weapons, horse equipment, jewelry, and ceramics are found in the burials of the Srostkin culture. These finds help to restore an idea of the daily life of the medieval population, its social structure, craft traditions and trade relations. Swords, spears, and battle axes were found in some graves, which indicates a high military organisation of the society. Horse burials, typical of steppe nomads, attest to the importance of cavalry. Women's burials are no less remarkable. They contain bronze mirrors decorated with ornaments, bracelets and rings that are sophisticated in manufacturing technology.

Who are these people who left the mysterious mounds and hillforts? According to research, the Srostkin culture was formed as a result of migrations of Turkic tribes from the Altai Mountains — Kimeks, Kipchaks and other ethnic groups. Archaeologists note that it covers vast territories — from the Ob region to the Irtysh and further south into Central Kazakhstan. From the point of view of historical geography, the area of the Srostkin culture intersects with the borders of the Kimek–Kipchak confederation, a state of the 8-11th centuries, which included various Turkic and Ugric tribes. It bordered Khazaria and Volga Bulgaria to the west, and the Uyghurs and Kyrgyzs to the east. After the collapse of the Kimek–Kipchak confederation, part of the population left for the Volga region and the Urals, while the other remained in Western Siberia, becoming the ancestors of the Siberian Tatars. Later, these lands became part of the Mongol Empire, which led to large-scale ethnocultural changes.

Shadows of the steppe: Kimek World of Upper Irtysh region

The turn of the millennium in the steppes of Eurasia is a time of insoluble contradictions, a clash of traditions, the rise and decline of nomadic powers. Vladislav Mogilnikov in his monograph “The Upper Irtysh region and the Altai steppes at the turn of the I-II millennia” reveals this era through the language of archeology. The study, based on the study of more than 200 burials and hundreds of artifacts, allows us to look at the Kimeks, a people who left a noticeable mark on history, but disappeared over the centuries.

Scattered finds on the territory of the Upper Irtysh region and the Altai steppes form a single picture of a nomadic world in which military organisation, religious rituals and material culture determined not only everyday life, but also the place of the people in the big politics of the steppe. The Kimek burials studied by Mogilnikov show not only ritual traditions, but also social stratification. The ornate burials of the nobility, the intricate designs of the mounds, in which the remains of horses and weapons were found, speak of a rigid social hierarchy. Warriors, rulers, artisans — everyone had their own symbolic “baggage” to the afterlife.

One of the key aspects of the study is the analysis of burial methods. Cremation and inhumation combined in one necropolis speak about a complex synthesis of traditions, about the Kimeks' ties with neighbouring peoples — Kyrgyz, Uyghurs, Oghuz Turks. This cultural fusion, as Mogilnikov emphasises, played a key role in the further development of the Turkic world.

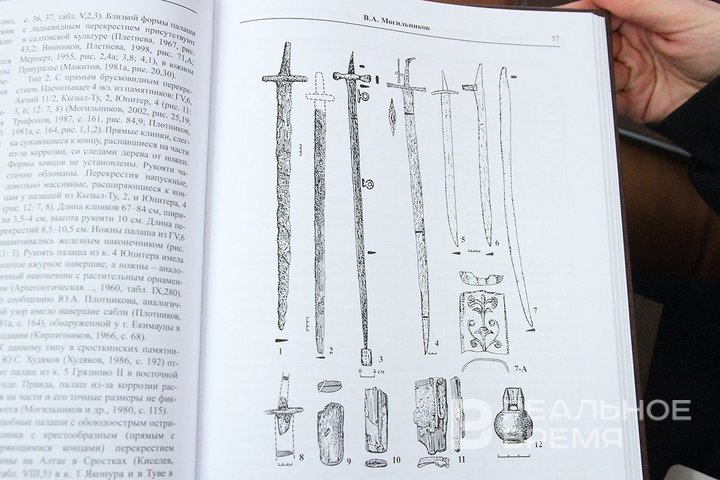

The military power of the Kimeks determined their status in the Eurasian steppes. Archaeology records a complex weapon system that combines local traditions and borrowings from neighbours. The bows found in the Kimek burials are the result of a long technological development. Their wood, horn, and sinew components allowed for a significant increase in range and accuracy. The same principle was later inherited by the Kipchaks and Mongols.

The arrowheads found in the Kimek mounds have analogies with Chinese and Central Asian samples, which indicates active contacts of nomads with neighbouring regions. Sabers and backswords are another evidence of military culture. The technique of making blades shows the influence of the Uyghurs and Sogdians. Kimek warriors also used elements of protective weapons: leather shells with metal plates, bracers, helmets. Their findings prove the high level of military affairs and serious clashes over control of territories.

For nomads, a horse is not just a means of transportation, but a part of their cultural and military identity. The remains of horses buried with the warriors are often found in the Kimek mounds. The elements of horse equipment — stirrups, bits, and harness — indicate the established riding system characteristic of the late Turkic peoples. The design of the bridle sets traces both local traditions and borrowings from the Chinese and Sogdians. Particularly interesting are the finds of waist headsets and belt distributors. These objects not only decorated the riders, but were also ethnocultural markers. The analysis of the Kimek artifacts shows their similarity to similar finds in the Volga region and the Southern Urals.

Household items and personal jewelry are an equally important part of the study. Among the finds are bronze and silver earrings, rings, mirrors, and bone combs. These things speak about the craft traditions and cultural contacts of the Kimeks. Shamanic attributes — bells, bone amulets — speak about the complex spiritual world of kimeks. Their religion, as Mogilnikov emphasises, combined shamanism, elements of Tengrianism and borrowed Buddhist practices.

Nomad сities and stone letters of the steppe: the archaeological portrait of the Uyghur Khaganate

The steppe, which, it would seem, was created for eternal nomadism, becomes the arena for the emergence of a powerful state. The Uyghur Khaganate is a state that managed to combine nomadic and settled traditions, speak the languages of the steppe and trade with the most powerful empires in the world. The book “Archeology of the Uyghur Khaganate”, prepared by a team of Mongolian researchers, is not just another scientific work. This is an archaeological chronicle that gives the opportunity to look into the past, where nomads built cities, carried out politics and created a unique culture that influenced future generations.

It is generally believed that nomadic peoples were only horsemen of the steppes, who did not know architecture, urbanism and complex engineering solutions. However, excavations in Mongolia, Tuva and Transbaikal prove the opposite. A study of 15 Uyghur cities described in the book shows that the Uyghurs created an extensive system of fortified settlements that were not only military strongholds, but also centres of craft, trade, and religious life. The most famous of them is Baybalyk, founded in 757 by order of Mo-yun Chur Qaghan. This city was a real gem of Uyghur urbanism. According to archaeological research, there were discovered:

- administrative buildings where key political decisions were made,

- artisan quarters where jewelry, household items, and weapons were produced,

- Buddhist temples and monasteries that confirm the active influence of Buddhism in the state,

- residential areas where the military elite, artisans, and merchants coexisted.

Archaeologists note that the urban layout of Baybalyk and other Uyghur centres was well thought out, and the fortress walls were built using a complex system of fortifications. Uyghur cities were not built chaotically, but according to clear engineering principles, proving the high level of organisation of society.

Another myth that the book destroys is the idea that nomadic peoples did not have their own written language. In fact, the Uyghurs not only used the Turkic manuscript, but also actively borrowed elements of Chinese and Sogdian writing. Inscriptions have been preserved on the stone steles and ritual structures found. Some of them are made in the ancient Uyghur language, some in Chinese and Sogdian. This clearly shows the level of political and cultural integration of the Uyghurs into the common system of Eurasian states. The most famous inscription is on the Selenga stone. It tells about the construction of Baybalyk, its significance for the khaganate and the events that led to the fall of the city after the invasion of the Kyrgyz in 840.

The Uyghur Khaganate occupied a strategic position in Central Asia, controlling the caravan routes of the Great Silk Road. Trade routes between China, Tibet, Central Asia and even Byzantium passed through it. Archaeological finds confirm this extent. Chinese silks and ceramics are evidence of trade with the Tang Empire. Sogdian silver coins are a sign of economic cooperation with the trading cities of Central Asia. Buddhist statues are traces of religious influence from India and Tibet. The authors of the book emphasise that the Uyghur elite actively used Buddhism as a tool for consolidating power and international politics. It was during this period that elements of Tibetan and Chinese Buddhism appeared in Uyghur culture, which was reflected in temple architecture, funeral rituals, and art.

One of the most interesting chapters of the book is an analysis of the religious situation in the Uyghur Khaganate. Unlike the previous Turkic states, the Uyghurs did not limit themselves to traditional Tengrianism. The state simultaneously coexisted:

- Buddhism — spread through contacts with China and Tibet,

- Manichaeism — came from Persia and spread among the elite,

- Tengrianism — an ancient religion of the Turkic peoples, which has retained its importance even in the face of the spread of new beliefs.

Archaeological finds show that Uyghur cities had a complex religious structure. For example, both Buddhist temples and Manichaean sanctuaries were found in Baibalyk. This proves that the Uyghurs managed to integrate different religions into a single state system, using them as a means of strengthening power.

“Archeology of the Uyghur Khaganate” is the first work that provides such a detailed analysis of archaeological finds of the 8-9th centuries in Mongolia. The authors collected a huge amount of information: 15 cities, 12 burial complexes, 5 ritual structures, dozens of artifacts. The work shows that Central Asia in the Middle Ages was not just a nomadic territory, but was a complex ecosystem where sedentary and steppe civilisations intersected. And the history of the Uyghur Khaganate is not only the past. This is the key to understanding the cultural processes that have shaped the modern face of Eurasia.

Ekaterina Petrova — a literary columnist for Realnoe Vremya online newspaper, the author of the telegram channel Buns with Poppy Seeds.