The Volga as part of cultural code

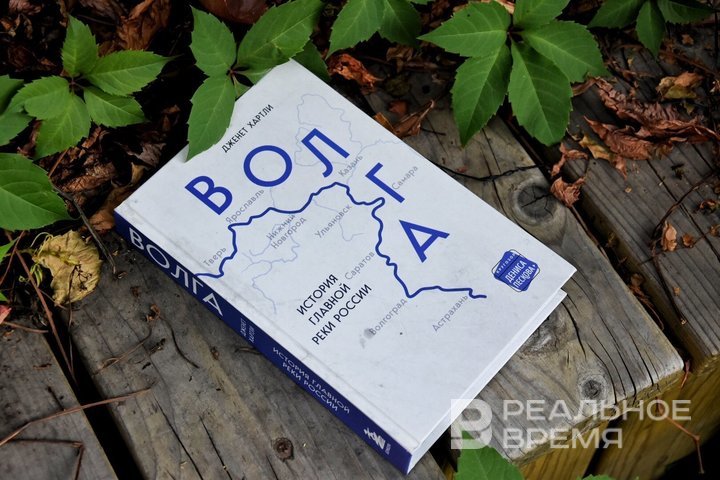

In her book ‘The Volga: A History of Russia’s Greatest River,’ Janet Hartley examines the river as a symbol of Russian culture as well as a border between East and West, Christianity and Islam, Russia and the world

The Volga River is not just a geographical feature. It is an artery that feeds the Russian soul. This is what history professor Janet Hartley writes in her book The Volga: A History of Russia's Greatest River. The author intertwines history, culture and politics in it revealing how the river shaped the Russian Empire, and then the Soviet Union. The Volga is not only a river washing the banks but also a real metaphor for the life and survival of peoples over the centuries.

Towards the centre of the Empire

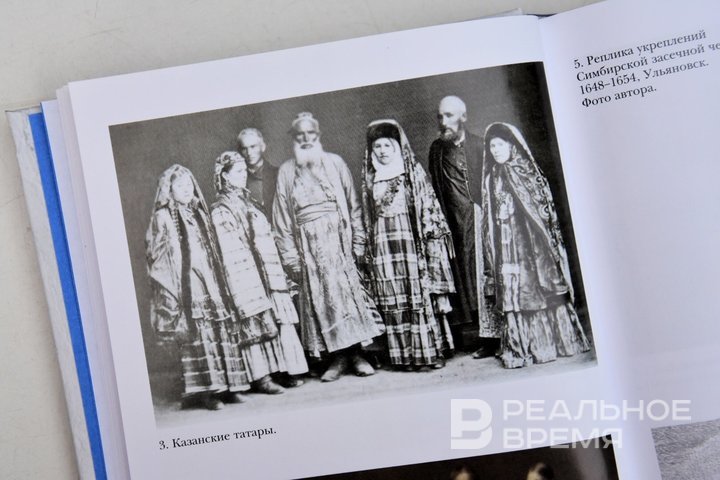

How can you tell the history of an entire country through the history of a river? How can a single artery unite and divide at the same time? Janet Hartley’s book The Volga: A History of Russia's Greatest River reveals how the river became an integral part of Russian identity and cultural code. The Volga not only connected peoples but also divided them creating a boundary between the Christian West and the Islamic East. It was a melting pot of peoples, from Vikings to Tatars, from Cossacks to German settlers.

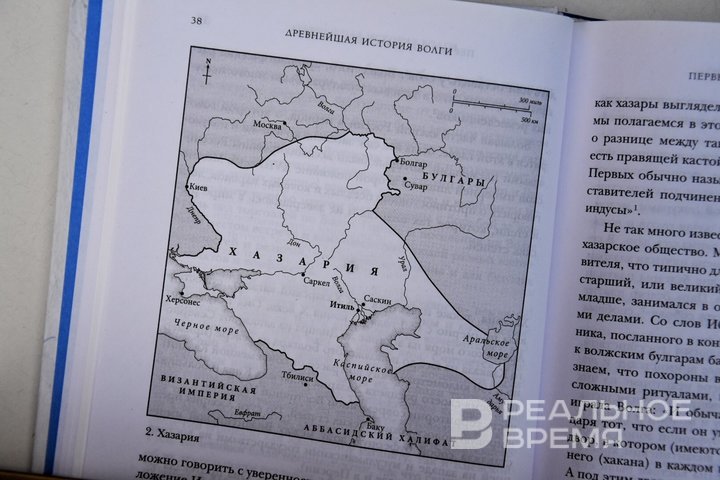

Hartley describes the Volga as a place where cultures, religions and political systems mixed. The author begins the story by mentioning the first states on the banks of the river — the Khazar Khaganate and Volga Bulgaria. Even in this early period, the river was not only a trade route but also a symbol of power over a vast territory. Hartley immerses the reader in an era when the Volga was a meeting point for a wide variety of peoples and beliefs, from animists and Buddhists to Orthodox Christians and Muslims.

Indeed, Volga lands such as Kazan and Astrakhan have historically been places of complex interactions where tensions between local cultures and the Russian state have led to dramatic events, from the conquests of Ivan the Terrible to the uprisings of the Cossacks and Tatars.

In the 16th century, the Volga became a symbol of the victories of Russian Orthodoxy. After taking Kazan and Astrakhan, Ivan the Terrible finally consolidated control over the river, which Hartley describes as a milestone in the history of the Russian Empire. She calls this process the beginning of the transformation of the Volga from a borderland into an axis of imperial power. But what was it like to live on this border? What was the cost this unity achieved at?

A river with many symbols

In Hartley’s book, the reader sees that the Volga was not only a symbol but also a theatre of real battles for resources and influence. In the 17th-18th centuries, major Cossack uprisings led by Stepan Razin and Yemelyan Pugachyov unfolded along its banks. Hartley immerses the reader in the atmosphere of rebellions and reprisals where the Volga takes on the image of resistance to the central government, and not just its stronghold.

The Battle of Stalingrad is one of the most famous pages in the history of the Volga. As Hartley notes, at that moment the river turned into a symbol of the survival of the entire nation. The victory in Stalingrad became a turning point in World War II and secured the Volga a place in the pantheon of national heroes.

But the Volga was not only an arena of battles. As Hartley shows, during the Soviet era, the river became a symbol of industrialisation and the victory of humans over nature. Large hydroelectric power stations built along its course changed the landscape and environment of the region. This decision was perceived at the time as a triumph of socialist progress, but modern criticism often raises the question of the cost of this progress for nature and local residents. Hartley asks important questions about how justified such changes are in an era when the environmental consequences are becoming increasingly obvious.

Hartley’s description of the modern problems facing the river is one of the most valuable aspects of the book is. Industrial pollution, overuse of water resources, climate change — all of this threatens the Volga’s unique ecosystem.

The Volga, according to the journalist, is not only one of the greatest rivers and the longest river in Europe but also the most beautiful river in the entire world. There is no better way to end this book than with the last words of that story: “Without the Volga, there would be no Russia.”

This environmental aspect takes the book to a new level of significance. In an era when the fight for environmental sustainability has become a global issue, the Volga, as a symbol of nature and culture, finds itself at the centre of discussions about the future. Environmental issues are already inextricably linked with questions of social and political stability. Hartley managed to create a canvas of Russian history through the prism of one river.

The book emphasises that the Volga is not just a symbol of statehood or military power, it is a living witness to the changes that occur over the centuries. From the Khazar Khaganate to the Battle of Stalingrad and the modern environmental crisis. At all times, the Volga has been at the epicentre of Russian history. However, a question arises: what are we doing today to preserve this priceless cultural and natural resource? Janet Hartley suggests not only looking at the past but also thinking about the future of the Volga and the future of the country at the same time.

Publisher: Bombora

Translation: A. Korobeynikov

Print length: 560 pages

Year: 2024

Age restriction: 12+

Ekaterina Petrova is a book reviewer of Realnoe Vremya online newspaper, the author of Poppy Seed Muffins Telegram channel and founder of the first online subscription book club Makulatura.