'Unknown Berlin': photos kept in family archives for 75 years

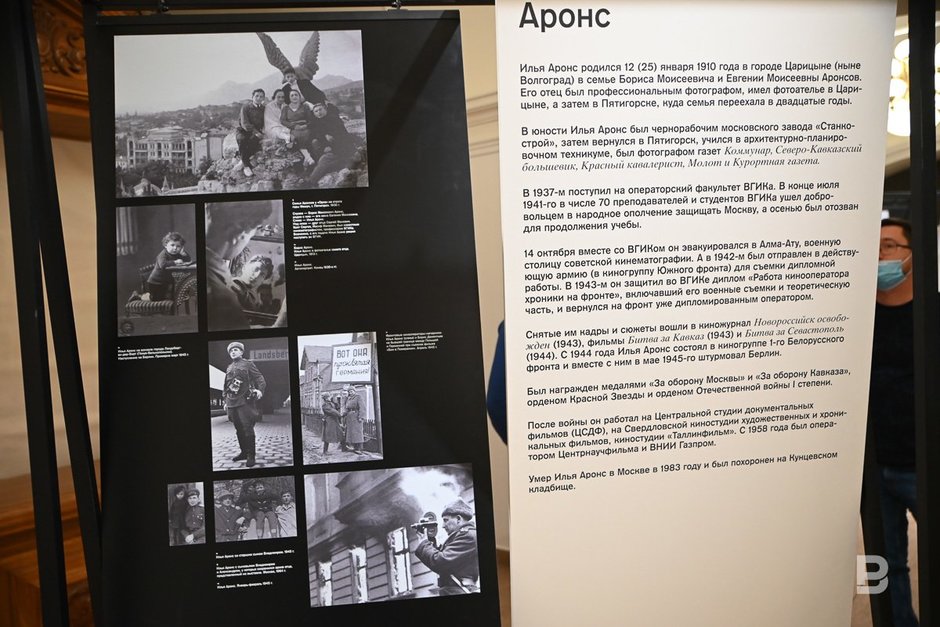

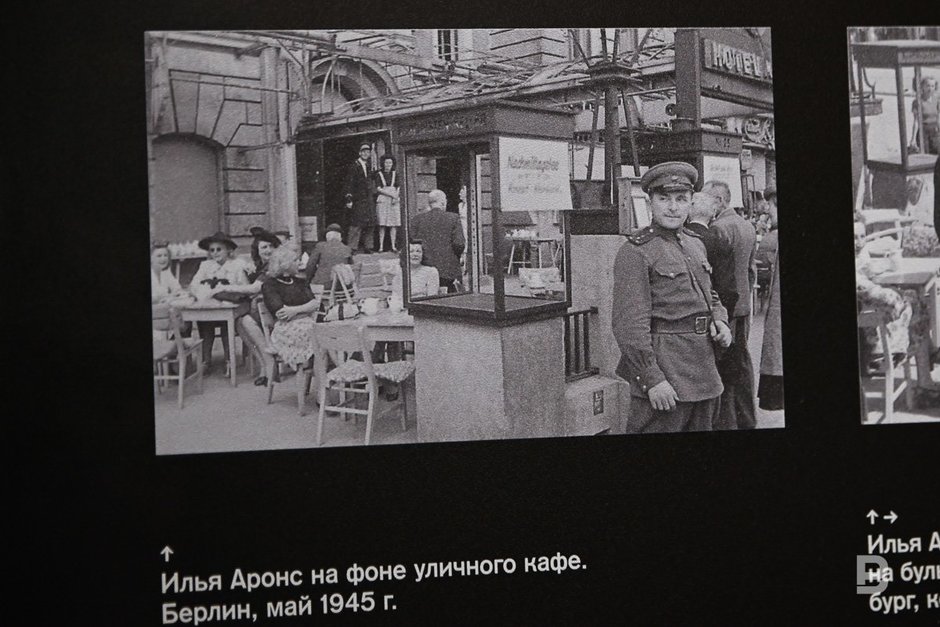

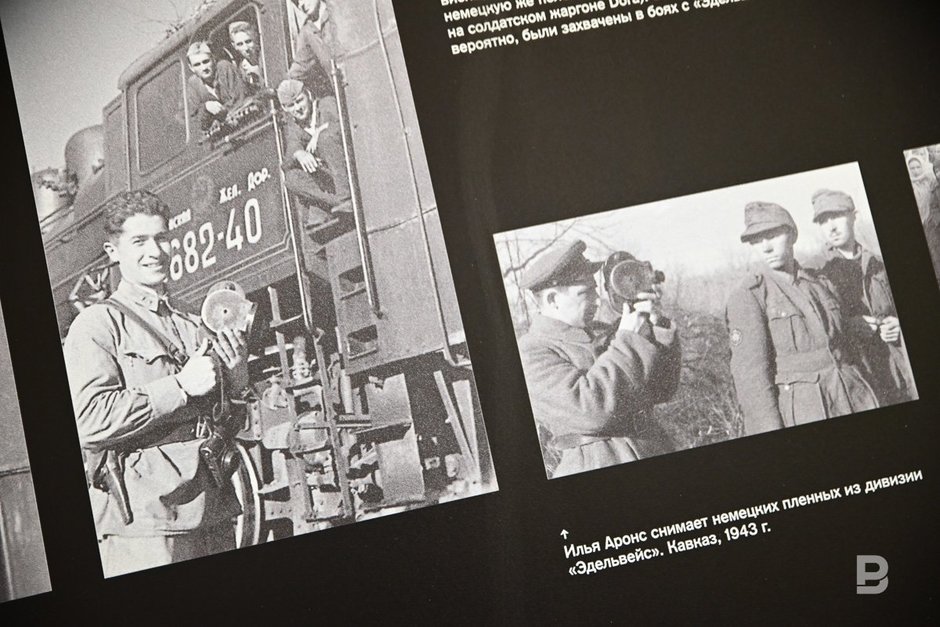

Previously unpublished works of front-line photographers Ilya Arons and Valery Ginzburg are presented at the National Museum of Tatarstan

The National Museum of Tatarstan has opened the photo exhibition “Unknown Berlin. May of 1945.” The works of Valery Ginzburg and Ilya Arons are becoming public for the first time — before that they were kept in family archives.

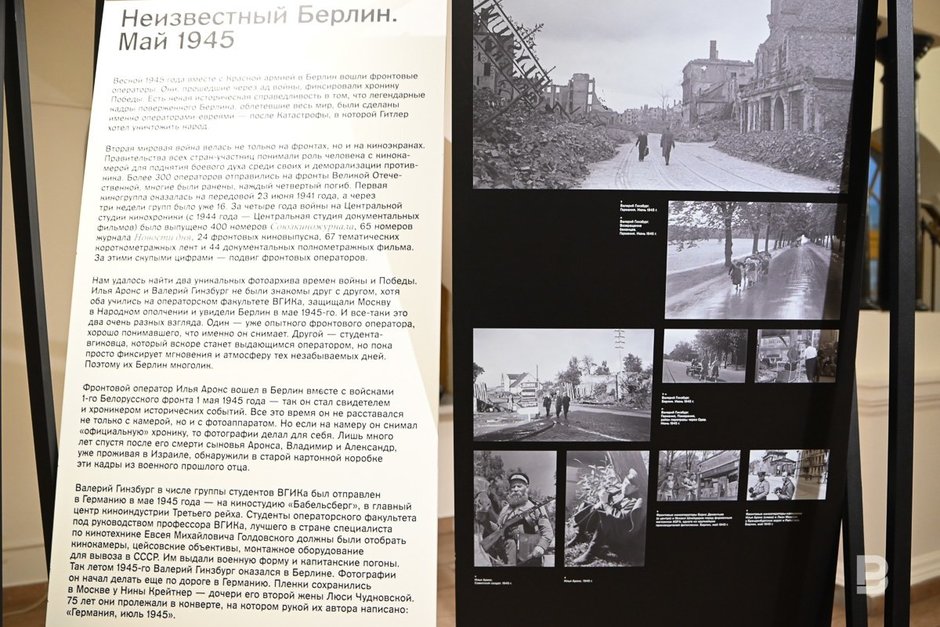

Two views on one victory

The exhibition was created in 2020, it was then that it first became public in Moscow at the Jewish Museum, which created the project together with the Tolerance Centre. The exhibition, which is small in volume but extremely rich in content, has become mobile. It has already visited Samara and Yaroslavl, and now it is being presented to the Kazan residents.

However, not the original photos themselves, but their pictures can be seen on several stands. All of them are provided with detailed information about the life and work of front-line photographers and newsreelers, military operations in the spring of 1945, the Southern and First Belorussian Fronts. Watching and reading to see the close interweaving of the war and the first peaceful days, caught by the artist's eye.

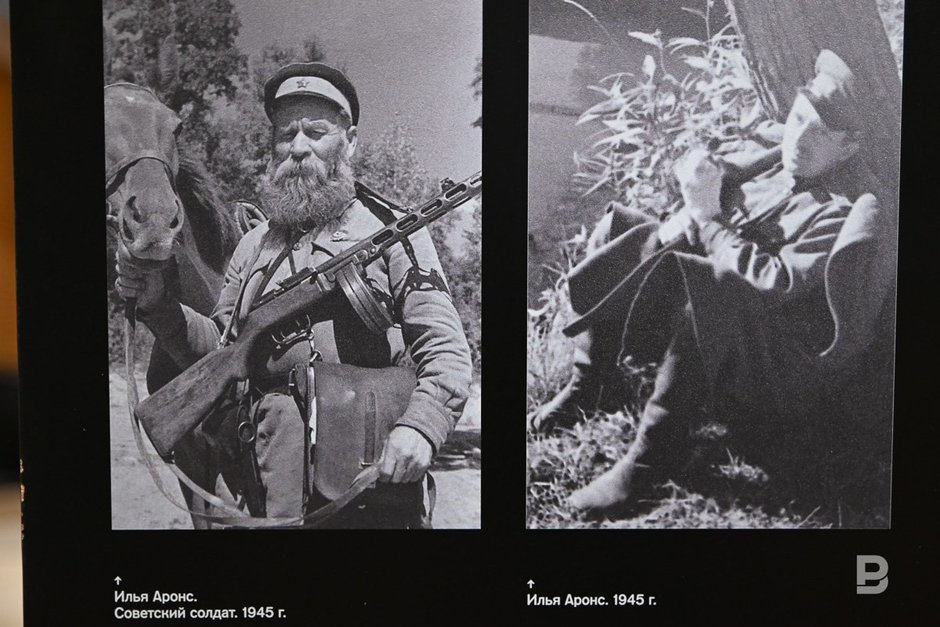

“The Jewish Museum deliberately posted these shots on the same topic, but by different photographers. If Ilya Arons was shooting as a reporter — he definitely wanted to capture the victory, then Valery Ginzburg was more interested in the artistic side of the issue. By the way, these front-line shots then was included in his cameraman's works," said the chief curator of the National Museum of the Republic of Tatarstan, Lilia Sattarova.

Rokossovsky in the campsite

According to the head of the Museum-Memorial of the Great Patriotic War, Alexander Alexandrov, Ilya Arons' photographs are interesting because they depict his colleagues, photographers and cameramen:

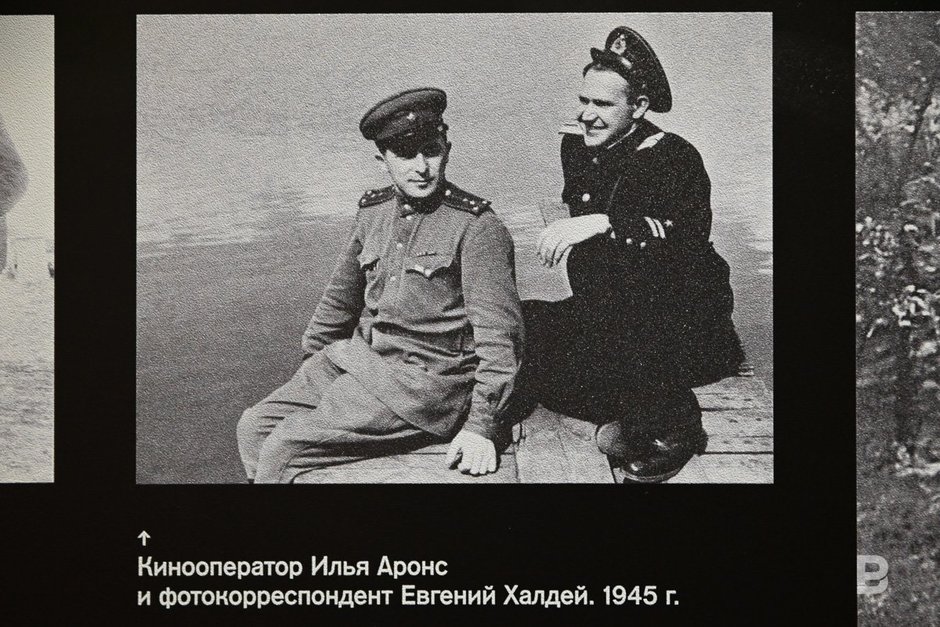

“We all know the famous photo of Yevgeny Khaldey with a flag on the Reichstag, but not everyone manages to find out what he looked like himself. There is a portrait of him at the exhibition, as well as many others, including iconic personalities of that time. We see not only staged photos, but also how they were made — with the eyes of another photographer who was watching what was happening. We see marshals in ordinary life, as well as setting up the peaceful life in the first post-war days.”

Indeed, where else can you “peek” Konstantin Rokossovsky, relaxed smoking a cigarette, peering into a flowering tree or, perhaps, into the sky through its foliage, Colonel-General of Aviation Sergey Rudenko or just the face of an unknown warrior. So, for example, the picture “Soviet Soldier” attracts attention — a bearded old man, holding a horse by the bridle with his right hand, and holding a rifle with his left.

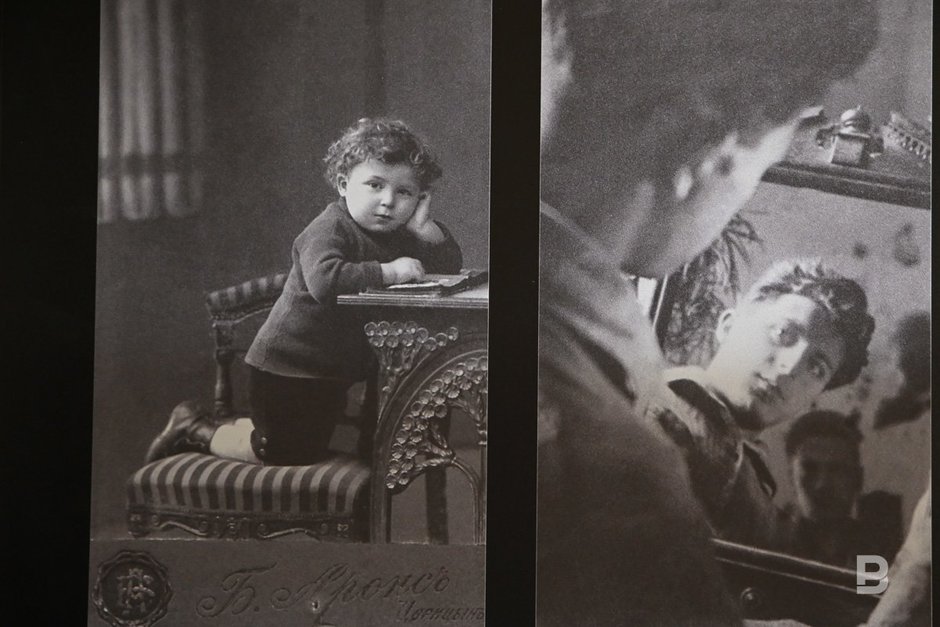

Couldn't save the family

Ilya Arons was 35 years old when the war ended, but he started it at the end of July 1941, when he joined the People's militia among 70 volunteer teachers of the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography. A year later, he was sent to the active army on the Southern Front. However, in July he was surrounded near Kharkov, the Southern Front was defeated, only some of its parts were able to escape, making their way to their own. After leaving the blockading cordon, Ilya Arons found out that his whole family was very close — in Pyatigorsk, seized by the Germans. To take his family out, he was provided with a car, but the way to the city was blocked by German tanks. At that time, in September 1942, his parents, sister Muza with the baby and grandmother were shot by the Nazis in Mineralnye Vody along with thousands of Jews.

The trouble did not break the photographer. He was awarded medals and the Order of the Patriotic War I degree. During peaceful days, he worked at the Central Documentary Film Studio in Sverdlovsk, as well as at Lenfilm.

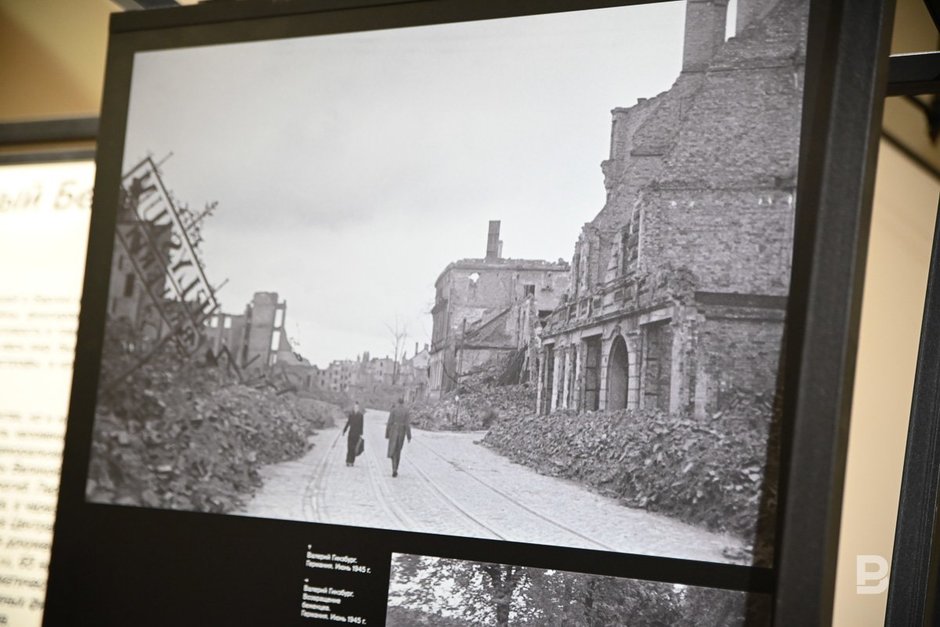

He suffered for his brother Alexander Galich

In the spring of 1945, front-line cameramen and photographers entered Berlin together with the Soviet Army, and a little later, after the victory, the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography sent a whole group of specialists to Berlin to analyse the materials of the Berlin film studio. Valery Ginzburg was among them, who at that time was only 20 years old. He had already been to the front, having gone to war as a 16-year-old volunteer, but due to illness he had to return to Moscow to be treated — he froze his feet in the trenches. Later he became a famous cinematographer, whose works received multiple awards, taught at the Department of Cinematography, but in 1976 he was fired — his older brother, poet-bard Alexander Galich emigrated. By the way, Valery Ginzburg made a documentary about him in 1989, and a year earlier he won a Nika Award as the best cinematographer.

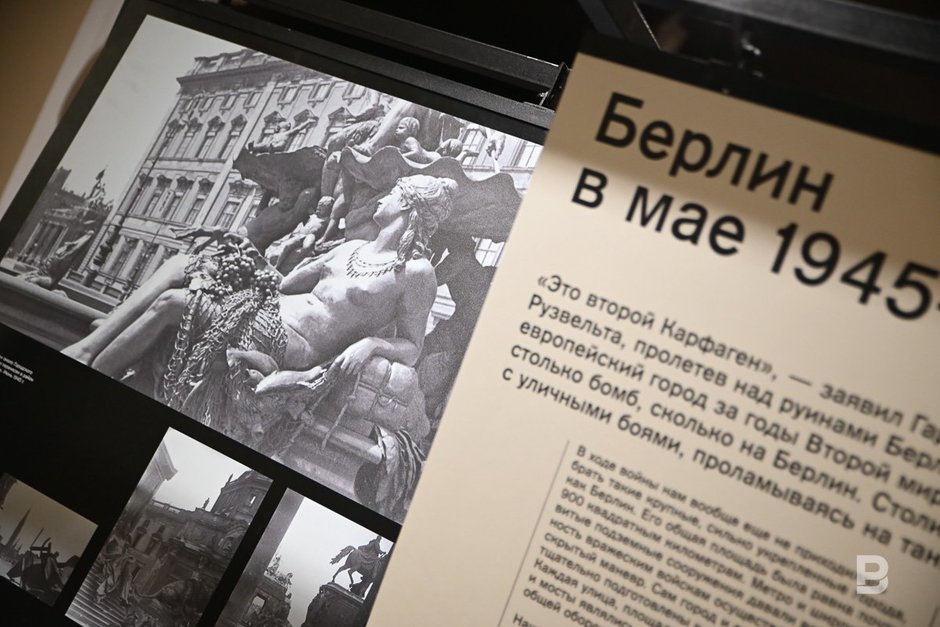

On one of the stands, it appears that all the photos of Ginzburg presented at the exhibition were kept for 75 years in an ordinary envelope, on which his handwriting was written “Germany, July 1945". In the pictures you can see the “Return of refugees” (a flock of women, cowering in the rain, walking on a wet road), miraculously preserved elements of the Neptune fountain near the City Palace in Berlin and the almost destroyed colonnade of the monument to Kaiser Wilhelm I, the Brandenburg Gate, the Reichstag, Berlin Cathedral, Kurfurstendamm Boulevard. There are also many just faces — children's, women's, men's — people starting life anew.

The exhibition is open until 1 December.