‘Tatar immigrants pointed out the ‘Muslim traits’ of the Japanese’

The image of Japan in perception of Tatar people in the beginning of the twentieth century

Interest in Japan of Tatarstan is increasing significantly. This is facilitated by different events, for example Putin's meeting with Shinzō Abe, the moving to Kul Sharif of the first printed in this country Koran, made according to 'samurai' technology. Our newspaper also published the article about this amazing country written by the Japanologist. The Kazan historian Liliya Gabdrafikova also joined the Japanese theme. In her newspaper column, written specially for Realnoe Vremya, she tells how the Eastern neighbour of Russia, located on the islands, became interesting to the Tartars a hundred years ago.

Go East!

The Tatar people throughout its history have been influenced by both the East and the West. Interestingly, even during the pagan times, the Tatars (more correctly, their ancestors — the Ancient Turks) had the stone monuments-idols always facing the sunrise. Therefore, the Ancient Turks prayed turning face to the East. According to the remark of the scientist Gali Rahim, in the ancient Turkic language the word 'forward' meant 'East'. He also wrote that 'the East was considered as advanced and Holy country'. Here it is necessary to notice that on the advanced achievements of the East the scholar-folklorist wrote in the 1920s, here you can see the pre-revolutionary discourse of the Tatar intellectuals of that time.

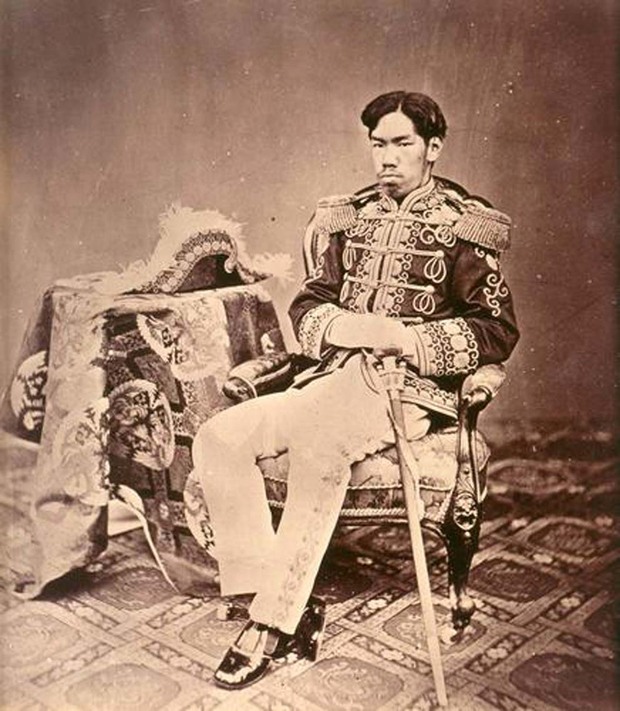

The Tatar educated circles considered various countries of the world — the European powers and the Ottoman Empire — as the examples of progress and high culture at the turn of XIX—XX centuries. Another example was Japan, which since the late nineteenth century made a huge leap forward, focusing mainly on science and technology. The reforms of Emperor Meiji were consonant with the ideology of the Tatar Jadids. He also spoke about the open dialogue with the world culture but, at the same time, he put in the forefront the unity and the success of the Japanese nation. The reform of Meiji, as well as Jadids' reforms, had a protective value. The bourgeois changes have almost not affected the Japanese traditionalism in the form of the foundations of spiritual culture, political system, private way of life.

About the changes that swept the distant Asian country it soon became known to the small circle of Tatar intellectuals. For example, a popular playwright Ğäliäsğar Kamal in the play 'Ochsh badbakhet' ('Three scoundrels'), written in 1899, gave to one of the characters the following remark: 'Ten years ago no one knew anything about the Japanese. But now the Japanese by educating themselves are creating something and compete with Europe, their merchants are everywhere. And we, Muslims, need to educate ourselves and learn to do something ourselves.'

By that time, in the Tatar society there had already been signs for some changes, and against this background, the success stories of Japan, that just not long ago lived according to traditional ideas, certainly had a powerful impact and encouraged. In addition to its belated modernization, the Tatars and the Japanese had other similarities. For example, the Tatars used to oppose themselves to the Western world and identified themselves mostly with the East, Asia. This was due to historical roots (the descendants of the Huns, the ancient Turks and other Eastern nations) and religion (Muslims traditionally were associated with the East).

Hospitable China

Japan and the Far East occupied a certain niche in the people's consciousness due to the increased migration flows in this region. The first settlers-Tatars appeared on the territory of China in the 1830s. Among them there were many people from Central Russia and the Volga Region. Muslims left their homes mainly because of the reluctance to serve in the Imperial Army. Until the military reforms of 1874, the military service lasted 25 years. Along with this, the Tatars were attracted by the new opportunities for the development of commercial affairs. For example, in 1851, China and Russia signed an agreement according to which in Yining County and Tarbagatay there were abolished trade tariffs for Russian citizens. Therefore, in the 1860s, a lot of Tatar immigrants lived in Yining County, most of the families were occupied in trade.

At the turn of XIX—XX centuries, in connection with the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway the Tatar migrants began to occupy the territory of Manchuria. They worked in the logging, participated in the construction of the railroad, and later began to actively develop the infrastructure of the new stations. In Harbin by 1904 there was formed the official Muslim community of the city. It is obvious that about China and border Japan some Tatars learned from the stories and letters of relatives and friends who left for a better share in the Far East.

Terra incognita at world's end

However, most inhabitants of the Russian Empire learned about Japan mainly after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. For example, in the Tatar folklore there preserved the different variations of folk songs about the Russo-Japanese War. They all tell of the plight of soldiers called to the front. In general, in the people's mind the image of Japan and the Japanese was quite blurred.

Although in rare cases, a military campaign, the stay in Japanese captivity and personal communication with representatives of another culture had continued. So, one of the Tatar soldiers returned home with his wife, a Japanese woman. They lived in the Simbirsk province in a Tatar village, and today the descendants of this couple live in Kazan. Of course, such moments had an impact on the public consciousness.

In the beginning of the tragic events many of the soldiers, according to Ğabdulla Tuqay, 'even approximately did not know where the war broke out and who were the Japanese'. In his article of 1906, the writer lamented the arrogance of the Russian rulers who dared to enter into a military conflict with such a powerful country as Japan.

Wondering what was the secret of the Japanese miracle, many Tatar intellectuals agreed on the fact that it was all about education and commitment. The well-known Kazan theologian Galimdzhan Barudi in his article published in 1908 also draws attention to the issues of education. He compared the number of students and teachers in Japan, analysed the number of schools and libraries and came to the conclusion that this country is second only to the US and the UK. In addition to technical progress, Galimdzhan hazrat emphasised the political maturity of the Japanese. 'In this regard, you should not wonder the high level of political rule and living conditions,' he wrote. 'Such progress level that seems unusual based on enlightenment and education, plus their natural inclination to diligent and honest work'.

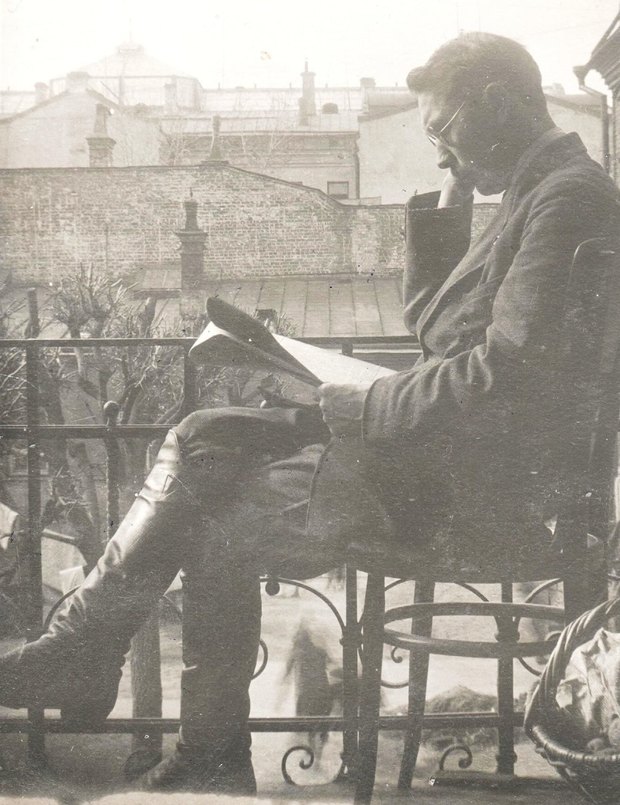

Before the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, the well-known public and political figure, a journalist Gabdurashid Ibragimov also knew nothing about Japan. The victory of Japan in the war had a strong impact on him, and after that, he had a desire to learn about this country from the inside. Subsequently, Ibragimov played a special role in promoting Japan among the Tatars. He first visited Japan in 1909 and lived there for almost six months. During this time, he managed to visit many settlements, cultural and social institutions, participated in public events, met with different people (he was interested in ordinary farmers, scientists, high-ranking officials and other figures). In order to understand the inner life of Japan better, the Tatar intellectual even began to study the Japanese language. Most of all, he admired 'the national spirit' of the Japanese people, a combination of Western innovation and Japanese tradition. The travel notes of G. Ibragimov about Japan were published in the Kazan newspaper 'Bayanel-khal' ('Statement of truth'). A tireless social activist, a supporter of pan-Islamic ideas G. Ibragimov later emigrated to Japan and lived there for the last years of his life from 1933 to 1944. It was during these years when the Muslim community of Japan was formed and the mosque in the port city of Kobe was built. His son, Ahmetmunir Ibragimov, graduated from one of the Japanese universities in 1913.

The interest in Japan from the Tatar community in the 1910s is indicated in the articles from the pen of other authors. For example, in 1915, on the pages of the Orenburg journal 'Shura' the series of articles 'Tour of Japan' by S. Urmanov was published. According to the historian R. Amirkhanov, in the early twentieth century, some Tatars conducted their commercial affairs in Tokyo.

Japanese cultural phenomenon

Thus, on the eve of 1917, the perception of Japan of some Tatars became more tangible. Obviously, the spread of photography and the development of printing, the appearance of publications with illustrations helped to form the visual image of distant Japan to the wider population. For example, in the work 'Autumn story' a young Gali Rahim compared the main character — the Tatar girl Gauhar — with 'a perfect Japanese woman'. The story was written in 1918.

Japan continued to appear in artistic and scientific texts of Tatar intellectuals in Soviet times. For example, the comedy by Tazi Gizzat 'The glorious epoch' published in 1936 begins with the monologue of one of character about Japan. Of course, in the light of the then political situation, the Country of the Rising Sun is represented as an imperialist aggressor. Meanwhile, the inclusion of a replica of the character of the play about Japan seems to be non-random. Tazi Gizzat succeeded as a writer due to the cultural heritage of the prerevolutionary period. The Turkologist Gibadulla Alparov in the late 1920s in the debate about the romanization of Tatar alphabet cited the example of Japan with its hieroglyphs. He opposed the romanization and insisted on the preservation of Arabic script. In one of its publications, the scientist noticed that some Tatar perceive the Latin alphabet as a symbol of Western civilisation. Therefore, the transition to the new script they associated with the hopes for rapid modernization of the Tatar culture. Alparov thought it was a great folly and called to look at Japan, where the most difficult hieroglyphs of the Japanese alphabet does not become an obstacle for the development of culture, as they had the powerful economic base.

The transformation of the traditional Tatar society cannot be imagined without the influence of other cultures. This impact has reflected at all levels of the Tatar reality — public and domestic. Sometimes the imitation of foreign cultures was too strong, blind imitation led to the fact that they adopted everything. In these circumstances, for the Tatar people in the beginning of XX century an excellent example of the artful combination of Western innovations and national traditions was Japan. The opening of the culture of the Country of the Rising Sun for the Tatar wider population began after 1905. Various publications in the media, personal visits of some of the leaders helped to create a positive image of the country. Appeared later in Japan Tatar immigrants confirmed this image, pointed out 'Muslim traits' of the Japanese: modesty, benevolence and diligence. The Tatar population of the Soviet Russia due to the political circumstances by the 1930s gradually changed its attitude towards Japan, seeing it not as an example to follow but rather as an imperialist aggressor. But that is the story for another historical research.

Reference

Gabdrafikova Liliya Ramilevna – Doctor of Historical Sciences, a chief researcher in Institute of History named after Sh. Mardzhani of the Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tatarstan.