‘The image of Catherine the Great and the idea of ‘revival’ are the result of some backstage compromise’

The monument to the Empress in Kazan: the comment of the historian

Among the public of Tatarstan there are serious disputes over the memorial sign to Catherine the Great, which Kazan authorities want to put on the bank of Nizhniy Kaban river. The columnist of Realnoe Vremya Alfrid Bustanov, who has studied various points of view on this issue, in his personal column, notes that among the members of the commission who will make the final decision about the monument there are neither historians nor the specialists in Islamic studies.

To 'immortalize' the memory

The memory has long become the subject of design, manipulation, and disputes in public space. There are hundreds of books written about how human memory is formed and can be directed in the desired direction. You needn't go far to find examples, just take a look around on 9 May and imagine the extent of state regulation in this area. It is impossible to think about it 'neutrally', even when it comes to subjective experiences, not to mention the official discourse and the public space. The monuments and the urban environment, in general, are also obvious fields for the construction of memory and… its destruction. The ability to forget is the characteristic of a human being. However, we forget not everything but on the basis of some priorities.

The recent news about the plan to establish the memorial sign in honor of Catherine the Great is a good occasion for thinking about the ideological component of public space and the politics of memory.

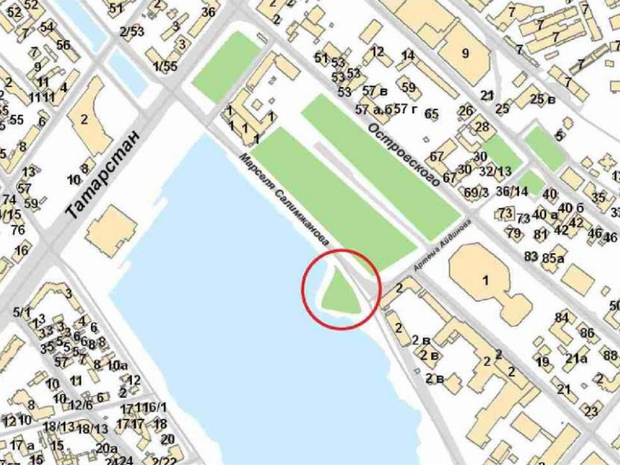

So, the document of the city administration refers to 'the perpetuation of the memory of historical events of 1767 – the decree of the Empress Catherine II, allowing Tatar merchants to build stone mosques and having a huge impact on the revival of Islam in Russia, the reflection of the identity and improvement of the city of Kazan'. The project itself is named with the Tatar word 'torgyzu' that has the meaning 'to revive' and 'to restore'. The supposed location of the monument is the waterfront of Nizhny Kaban lake on Marcel Salimzhanov Street, opposite to the Staro-Tatar Sloboda with those stone mosques that were 'allowed to build'.

The Catherine model of relations with Mahometans

Since in the commision there is no a single historian or expert on Islam (which is amazing), a few words about the essence of this initiative seem to me to be appropriate.

I will start with lexicology. The word 'torgyzu' implies that something that had already occurred, ceased its existence, but comes back to life again. If to apply to our case, obviously, it is assumed that Islam in Russia in 1767 was brought into such a condition that it was necessary to 'restore' and 'revive' it. And this, in its turn, gives the idea about some disastrous effects of the integration of the region into the Russian state, since the Islamic culture fell into decay for two centuries.

'The policy of Catherine II was aimed not at 'the restoration' but the creation of new structures in order to go away from the open confrontation with Islam and to define a legitimate niche for the functioning of religion, to make Islam legitimate and manageable.' Photo: izo-museum.ru (Rokotov F. S., Portrait of Catherine II)

This idea is not only questionable from a political point of view but does not correspond the historical realities. The fans of tragic stories about the 'ruin' I send to the recent monograph by Agnes Kefeli for a detailed discussion of the complexity of interfaith relations and identities in the Volga region. The absence of lively cultural life among the Muslim of the Empire until Catherine the Second is a historiographical myth, caused by exaggerated attention to relations between the state and religion. Islamic texts of the seventeenth century, where there is no a word about politics, gather dust on the shelves of libraries, but their existence, like the existence of different from the state forms of existence of Islamic culture is not subject to any doubt.

Moreover, the creation of the Catherine model of tolerance towards Islam has nothing to do with what had been previously practiced in the Russian Empire: the state first turned to Islam in order to create loyal Islamic institutions that would serve as a mediator between the authorities and the closed communities of Muslims. This model was created in the country with an eye on the management structure of Islam in the Ottoman Empire – it has been written much about it by the American authors Robert Crews and Mustafa Tuna. Of course, you can build historical memory on the basis of the illiterate stories of the tour guides, but then you should honestly confess in it.

Again: the policy of Catherine II was aimed not at 'the restoration' but the creation of new structures in order to go away from the open confrontation with Islam and to define a legitimate niche for the functioning of religion, to make Islam legitimate and manageable.

The policy of forced Christianization was not successful, and it became obvious that they should look for forms of peaceful coexistence. However, the state reserved the right to define what Islam was 'good' and what Islam was 'bad' since it itself became to form Islamic institutions and actively influence them through the exams in the Orenburg Muslim Spiritual Assembly, the issuance of licenses (edicts) and keeping the registers. The Catherine model lasted virtually unchanged until the second half of the XIX century when Muslims started to integrate more into Imperial space and even to form their political platform. By the way, in the Middle Asia until 1917 the Empire used the policy of ignoring Islam: the Muslims world without state support was supposed to die itself and to open the way for the cultural assimilation.

'The state reserved the right to define what Islam was 'good' and what Islam was 'bad', since it itself became to form Islamic institutions and actively influence them through the exams in the Orenburg Muslim Spiritual Assembly, the issuance of licenses (edicts) and keeping the registers.' Photo: posredi.ru (the building of the Orenburg Spiritual Assembly in Ufa)

Not without participation of puritans from Islam

Of course, the desire to establish a monument for the formation of historical memory is quite understandable. And, perhaps, the image of Catherine II and the idea of 'revival' are the result of some backstage compromise, since the Islamic factor in the Republic regularly speaks against establishment of monuments to prominent Tatar figures of history. The main argument here is the infamous ban on depiction of living beings in Islam.

I must say that it's quite unfavorable position, because nature abhors a vacuum: the assignment of public space will occur without participation of the puritans from Islam. A brilliant analysis of pseudo-ban for images in Islamic art you can find in the article by V. N. Nastich.

The critics can suppress the example of the development of sculpture in modern Iran by anti-Shia propaganda, but there is no escaping from the culture of photograph of Muslims of Russia and especially from the Soviet tradition of the creation of the images of Tatar enlighteners (Kol Gali, Utyz-Imyani, Kursavi and others), whose portraits are figments of someone's unsophisticated imagination. That is, a generilised portrait of Kursavi on a school wall is allowed, but the monument on the street is not? About the fans of selfies in the muftiats I'd better say nothing.

'There is no escaping from the culture of photograph of Muslims of Russia and especially from the Soviet tradition of the creation of the images of Tatar enlighteners (Kol Gali, Utyz-Imyani, Kursavi and others), whose portraits are figments of someone's unsophisticated imagination.' Photo: millattashlar.ru (Kursavi Abu Nasr)

It is clear that the establishment of the monuments, their opening and functioning is connected with the whole ceremony, largely inherited from Soviet practices of commemoration with wreaths, poems and ribbons. All this also causes a negative reaction from Muslim-purists. But the action itself and the power of the symbol are much more important in this context than a theological discussion about the boundaries of what is permitted. Like the rash choice of symbols so the passivity of the public in this matter (including the complete denial of public commemoration practices) can lead to serious conflicts. As an example, the hottest battles around the monument to Ermak in Tyumen – this idea is perceived in the city as a reminder of the subordinate position of the Siberian Tatars. We have the same story: for some it is the heroic past, for others — the trauma memory.

All that have been said, in my opinion, need to be considered in the discussion of the project of the monument opposite Staro-Tatar Sloboda, as this urban space is very densely filled with historical memory and the careless treatment with it can cause irritation both at the level of public perception and at the level of modern academic view of the history of Islam in Russia.

Reference

Alfrid Bustanov — Professor of TAIF company on the history of Islamic peoples of Russia, European University at St. Petersburg.

- Scientific degree: Ph.D., the University of Amsterdam.

- Research interests: history of Islam in Northern Eurasia, Oriental studies in Russia and the Soviet Union, Tatar History and Literature.

- Graduated with honours from Omsk State University named after F. M. Dostoevsky (the Department of History) in 2009 and postgraduate studies at the Department of Eastern Studies at the University of Amsterdam in 2013

- The author of five monographs in Russian, Tatar and English languages and about 40 scientific articles.