''How do they offer to solve the problem of non-Russian population? To either assimilate or destroy''

Russian ethnic sociologists compared notes in Kazan

A conference held by the Institute of History of the Tatarstan Academy of Sciences once in two years is called 'Positive Experience in Studies and Regulation of Ethno-Social and Cultural Processes in Russian Regions'. And this made one of the speakers of the plenary session on 6 September ask a question: ''Why should only positive experience be studied? Both negative experience and negative tendencies should be studied.'' Realnoe Vremya's correspondent visited the conference and found out why the term ''tolerance'' was going extinct in the professional community, how modern-time ethnic sociologists solved the main problem ''What the Russian nation is?'' and which of the ''tendencies'' could be called more negative.

''In Bashkortostan, the language problem, unfortunately, was very topical''

However, as one of the participants of the conference said to the author of these lines before it began, Tatarstan didn't have ethnic and social experience, not to mention tendencies. For instance, even one year ago, at the height of the language problem, according to her, sociologists didn't detect any interest in it among the population in Tatarstan. ''Salaries, quality of life are what concerned people, not compulsory mother tongue classes. Actually, this concerned only a narrow stratum of the intelligentsia and you, journalists. And it was the most topical issue in the last years! In our sphere, everything is nice and quiet.''

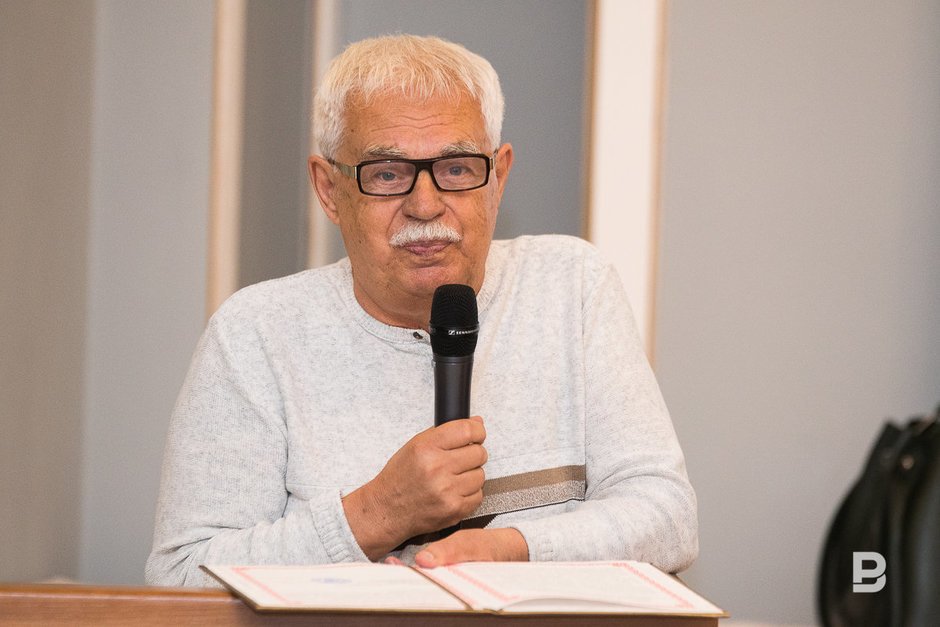

Ufa professor, Doctor of Sociological Sciences Rushan Gallyamov whom we managed to talk with after the conference didn't agree with it:

''In Bashkortostan, the language problem, unfortunately, was very topical, first of all, because society divided to a certain extent. On the one hand, the federal centre's firm position turned into a well-organised, planned campaign because radicals, public activists, state-run Bashkir and even Tatar national organisations stopped speaking after two-three protests. In addition, the protest movement against the cancellation of compulsory Bashkir classes at school coincided with the political component, the domestic political fight for power in the republic. Was there any sociological research? Yes, of course, I judge not only by protests – sociological research also provided a corresponding picture.''

Director of the Administration on National Politics of the Tatarstan President's Department for Domestic Politics Danil Mustafin didn't agree, though for other reasons. In his speech, he admitted Tatarstan's ''constant attention'' to ethnic and religious affairs and that the region realised the importance of the ''management of the process''. For this purpose, about 20 sociological research is done every year, 9 of them are ethnic and religious. ''The republic's national composition has changed,'' the speaker explained this attention, ''In 2002, we had 115 ethnicities. According to the results of the last census, their number has increased to 173. The religious picture is also changing.''

'Always together'

Speaking the press release's rough language, the sociologists gathered in Kazan to ''draw some conclusions of studying the complicated picture of the ethnic and social reality of Russian society''. As the guru of Russian sociology Leokadiya Drobizheva noted later in her speech, indeed, this year there is made an attempt to generalise what is fulfilled as the State National Politics Strategy (SNPS) until 2025. As it was adopted almost six years ago, there can be made amendments to it because, first of all, ''certain events happened'', secondly, science also developed meanwhile.

But the speakers opened the plenary session with reading welcome speeches, which, as strange as it might sound, also included some information. Everyone remembered how the first ethnic and sociological research was done in the USSR in the 1967-1968s in Tatarstan (or, more precisely in Laishevo District). And it also studied interethnic relations.

President of the Russian Society of Sociologists Valery Mansurov paid attention that the conference's name fairly included not only studies of ethnic and social processes but also their regulation whose fulfilment is up to power:

''I've recently been to Tyva. And I was surprised not only at research but precisely the regulation of ethnic and social processes in this region. They translate books on ethnic sociology into the Tuvan language and teach the 3-5 th graders with them! The teachers I saw them are great people!''

Leokadiya Drobizheva, in turn, noted that the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, which she represents (she's an honourable doctor there), was also founded in 1968 and ended her speech with words in Tatar: ''always together''.

Debate on 'Russian nation' is getting hotter

At the plenary session itself, Leokadiya Drobizheva gave a speech on 'Ethnicity and Interethnic Relations in the State National Politics Strategy in Ethnic and Political Discourse and Mass Consciousness'. And she was more serious, of course. Speaking about the changes happening Russian sociology, she noted the term ''tolerance'' was going extinct in sociology because its sociological meaning devaluated. This is why it's substituted in the SNPS by the term ''interethnic agreement'', which 95% of population misunderstands.

According to her, the question about the Russian national and all-Russian identity and how to introduce it into legal space causes the biggest number of debates when discussing the SNPS.

''There are two positions here,'' Drobizheva reminded the audience. ''Political expert Mikhail Remizov expressed the first one clearly: 'The unity of our culture is based on Russian culture, Russian language and historical memory.' That's to say, Russians are the foundation of the Russian nation, and others only join them. The second position is that we don't have a Russian civic identity because we don't have a civic society either, while the Russian nation is a complex institution, including multi-ethnic.''

Rushan Gallyamov commented on this part. He says the constructivist position that suggests that ''being Russian'', which is the ethnic foundation of the Russian nation, is raising its head again.

''It was actively protected and propagated in the 90s. But then it took a back seat. From a perspective of the ethnic, political establishment of regions where non-Russians are the majority, it's inferior because how to solve the problem of the non-Russian population this way? To assimilate or destroy. The second option is impossible in the 21 st century, moreover, Russia has never destroyed peoples, at least, completely (except the Cherkess who were either killed or emigrated to Turkey). Russia has always absorbed like a sponge and has always been a complex state ethnically. And the majority of scientists supports this position now, it's a mainstream anyway. But we see the constructivist concept is also reviving. But it's a direct way to an interethnic war in the country.''