''Each of us is in more advantageous position even to a brilliant writer-predecessor''

Sergey Zenkin, a literary scholar and translator, tells about why the theory of literature is a science for a wide public

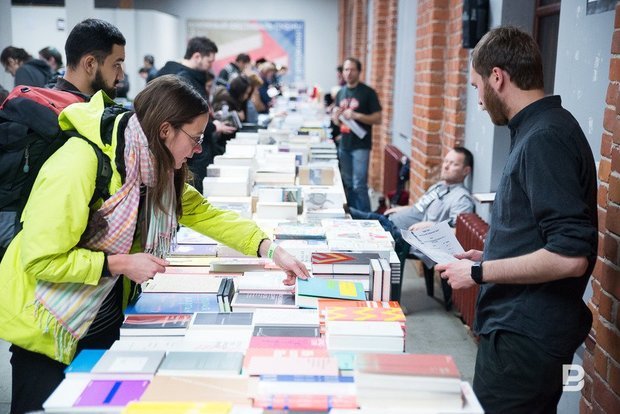

Sergey Zenkin, a literary critic, translator, Doctor of Philology, gave a lecture at the Winter Book Festival in the contemporary culture centre Smena in Kazan on December 10th. He came to Kazan with the support of the publishing house Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie [New literary review] and presented his book The Theory of Literature: Problems and Results, which appeals not to writers but readers and teaches them to distinguish good texts from 'schlock'. In the first part of the interview to Realnoe Vremya, the scholar tells about the nature of translation work and its important mission in establishing understanding between people of different cultures. In particular, how the inaccurate translation of Western poets by Zhukovsky influenced the development of Russian poetry.

In an interview you said that studying the theory of literature gives you aesthetic enjoyment. Can the subject be interesting to a wider public?

My lecture is just right called 'Why does literature need theory?', its main idea is that modern literature theory is intended not for writers. Of course, they try to use it, but more for playing than as a normative rule. The theory of literature is addressed mainly to readers, whom it makes sense to teach sensible, creative, and critical attitude to the texts they read. And not only to literary texts. In modern culture there are many texts that approach to literary ones by its structure, for example, advertising ones. One needs to know how to enjoy a good advertisement, but also to be critical to a deception it can hide.

My lecture is just right called 'Why does literature need theory?', its main idea is that modern literature theory is intended not for writers. Of course, they try to use it, but more for playing than as a normative rule

What are the main problems of the theory of literature?

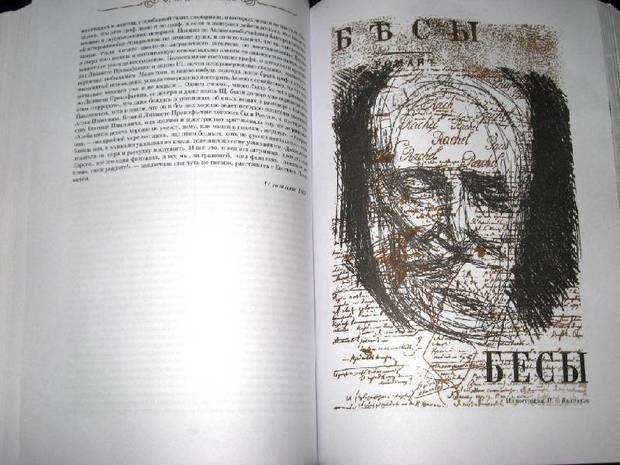

I consider in my book some problems associated with reading. For example, texts are usually heterogeneous. They consist of different parts, segments, these segments clash with each other. The text can contain poetry and prose, and how they are read differently. There is a story about someone's life, and there is an ideological interpretation of this life. Moreover, even the art quality of the same text may vary. The writer can give a slack somewhere and to write badly, but he or she can also write badly intentionally. For example, if we open at a random place the novel by Dostoevsky Demons and find the poems by Captain Lebyadkin, we will be greatly mistaken if judging by this passage the quality of the whole text. The first skill that the readers need to develop is to take into account the heterogeneity of the text, the combination of different parts, different languages of culture, to be able to distinguish them.

Can the writer write a text to be it unpleasant to read?

Yes, literature uses the so-called method of defamiliarisation. Writers intentionally create strange, unusual texts, change our view about how to write. Many modern writers deliberately write not how the reader would like: difficult, confusing, with shocking effects, thereby stimulating readers' work. And you need to learn to distinguish such deliberate effects of defamiliarisation from simple incompetence, which is also found in plenty. It is the skill of the reader.

''For example, if we open at a random place the novel by Dostoevsky Demons and find the poems by Captain Lebyadkin, we will be greatly mistaken if judging by this passage the quality of the whole text. The first skill that the readers need to develop is to take into account the heterogeneity of the text.'' Photo: labirint.ru

Zhukovsky did inaccurate translation. Nobody translates like this anymore

When getting education, the translators are told that they should translate not words but thoughts. Does this mean that interpreter as if retells the text, that it is already their work?

I never did retelling. I have always strived, especially as an editor, to exact translation. The main task of the editor is to clarify the translation. Not approximation to the norms of modern language (for example, the correction of stylistic errors), it is not so important. The main thing when translating is a deeper understanding of the original text and a more appropriate rendition. Of course, you have to comply with the current state of our culture, the level and composition of knowledge of potential readers, to apply complex strategies of adaptation of the source text to what is called the reader's horizon of expectations. You have to explain the text — sometimes within the translation itself, sometimes outside it, adding comments. Anyway, the task of the translator is to accurately and adequately convey the text to the reader for whom it was not intended, to help our contemporaries to understand it, who live in another country, and often in a different time than the author.

''There are historically important examples of such inaccurate but very important in the culture translations — for example, translations by Zhukovsky of Western poetry. He did not aspire to absolute accuracy, at that time there was no such task; nevertheless, his translations had an enormous influence on the development of Russian poetry.'' Photo: hermitagemuseum.org (I. Reymers. The Portrait of Vasily Andreevich Zhukovsky. 1837)

They say Marshak wrote Shakespeare in a new fashion. It turns out, it is not a usual story?

I think that the translator's work is similar to the work of a servant. They need to be effective and unobtrusive. Therefore, a good translation is invisible translation. If the translator shows off, it might be interesting, but it won't be a translation, but rather, another form of activity. Of course, there are historically important examples of such inaccurate but very important in the culture translations — for example, translations by Zhukovsky of Western poetry. He did not aspire to absolute accuracy, at that time there was no such task; nevertheless, his translations had an enormous influence on the development of Russian poetry. The modern translation is based on other principles.

In this respect, literary criticism, which you also do, is, in fact, the translation from Russian to Russian?

Not exactly. The study of belletristic literature is its understanding in scientific language, which is fundamentally different from the translation: they have different orientation, different functions, usually different people doing it. The language of science is, in principle, not national. Of course, science is inevitably stated in a particular language (English, French), but with the setting on maximum transparency for other cultures. If in the literature for a long time there has been the cult of the national language, it is believed that the task of the writer — more deeply to reveal, to realize the possibilities of their language in its difference from others, then the task of the theorist of literature — to reduce the variety of national literatures to some universal, scientifically, not intuitively grasped structures and laws.

To understand what the author hasn't understood yet

Are you more interested in translating scientific texts?

I have tried to translate belletristic, in the 1990s I translated several novels from French, and they were published. But I felt that many others also could do that. But translating some theoretical, philosophical texts — this, perhaps, I can do better than many other people, which is more enticing.

Do these texts attract you by the language they are written in or the ideas they contain?

It is more complicated thing. As a researcher as well as a translator, I try to look in scientific, philosophical, ideological texts not only clearly expressed ideas. I try to identify, draw out and systematize the intuitions, images, metaphors, productive but not completely thought over by the authors text components. They can be his weaknesses, like infeasibilities, contradictions, flaws, but they may hide his power because in productive metaphors and, moreover, in productive contradictions there can be found such possibilities of thought, which the author has not thoroughly expressed yet in the form of ideas. And we, his successors, can take them up and use.

''Compared to a writer who albeit brilliantly was writing a hundred or two hundred years ago, I have the advantage that I know about what happened after, I know a lot of unknown to him events and texts.'' Photo: Maksim Platonov

Is it something about the greatness of mind, about the divine spark, which is implied and accepted by those who are ready to accept the idea?

Each of us is in a more advantageous position to predecessors simply because we have a different, richer experience. Compared to a writer who albeit brilliantly was writing a hundred or two hundred years ago, I have the advantage that I know about what happened after, I know a lot of unknown to him events and texts. This allows me to find not quite mastered by him 'sub-ideas', which may be no less important to us than what he clearly expressed.

To be continued