Representatives of the Union of Writers of Russia outraged by the compliance with copyright law

Director Konstantin Bogomolov asked Medinsky to sort out the copyright on Mikhail Bulgakov's novel “The Master and Margarita”

At a press conference at TASS, member of the board of the Union of Writers of Russia and President of the Eurasian Patent Office Grigory Ivliev reported that “leading cultural figures” had contacted First Secretary of the Union of Writers of Russia Vladimir Medinsky, among whom only director Konstantin Bogomolov was named. In his appeal, he asks for a legal assessment and an examination of the legal situation that has developed around Mikhail Bulgakov's novel “The Master and Margarita.” Read about the confusion surrounding the copyright of the manuscript, why it is remembered now and what are the representatives of the Union of Russian Writers unhappy with in the report of book reviewer of Realnoe Vremya Ekaterina Petrova.

Manuscripts don't burn

Mikhail Bulgakov began work on the novel The Master and Margarita in 1928 and continued it until his death in 1940. In 1930, the writer destroyed the first version of the novel but later restored the text and continued working. By the time of Bulgakov's death, the novel remained unpublished, and his widow Yelena Bulgakova took on the task of preparing the text for publication.

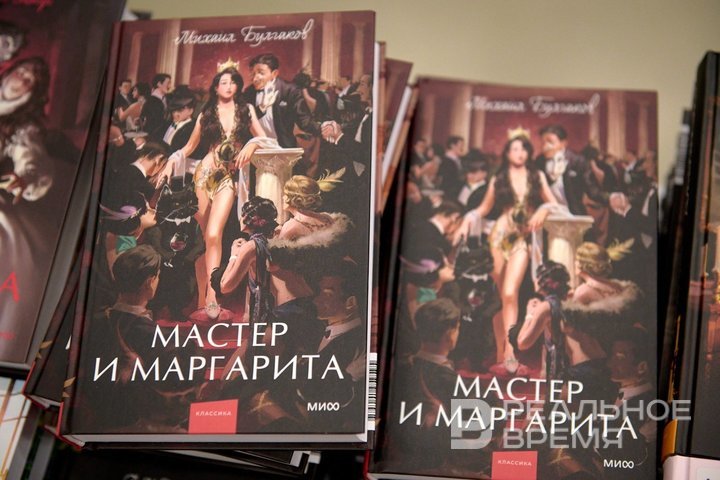

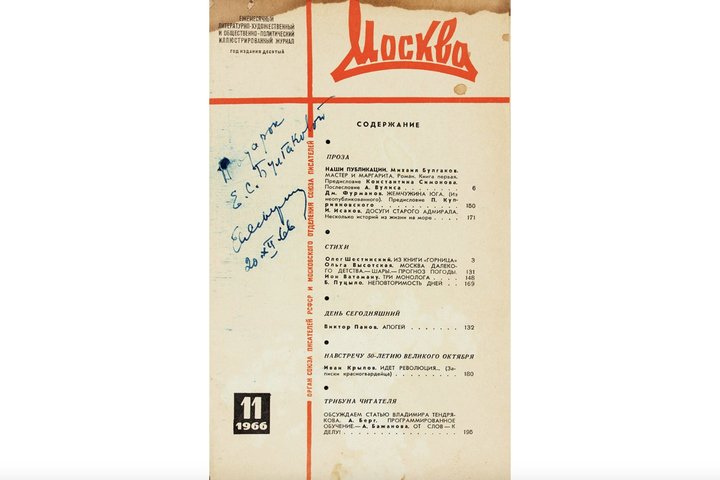

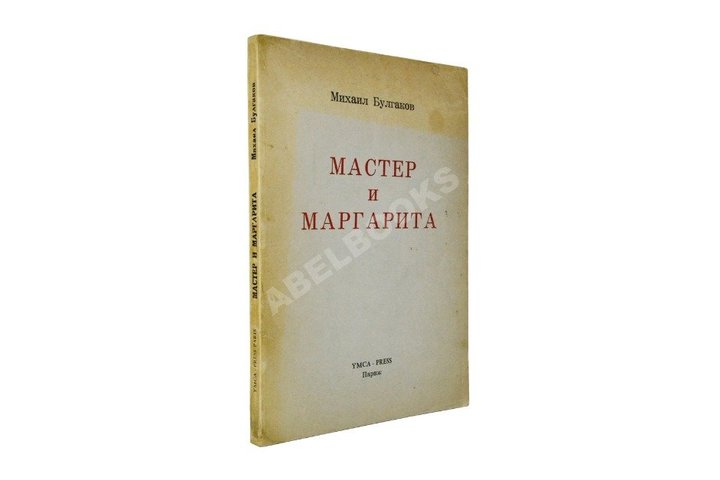

The novel was first published in an abridged form in Moscow magazine in No. 11 in 1966 and No. 1 in 1967, with a preface by Konstantin Simonov and an afterword by Abram Vulis. About 12% of the text was removed, including scenes with nudity and Woland's thoughts about Muscovites. The first one-volume edition of the novel in Russian was published in 1967 in Paris by YMCA-Press, reproducing the magazine version. In 1969, the Posev publishing house in Frankfurt am Main released a version that included the previously removed fragments, highlighted in italics.

In the USSR, the complete edition of the novel appeared in 1973 by the Khudozhestvennaya Literatura publishing house, although the text was edited by A.A. Saakyants. However, the editorial version of this edition contained more than 3,000 differences from the text prepared by the writer's widow. The circulation of this edition was 30,000 copies, most of which were sent abroad or to the personal libraries of nomenklatura workers.

In 1975 and 1978, reprints followed in print runs of 10,000 and 50,000 copies, respectively, and in 1980 and 1984 — 100,000 copies each. Due to the limited print runs for that time, the novel quickly became scarce, and its price on the black market reached 60-200 rubles, with the official price being 1.53 rubles. In 1989, L. M. Yanovskaya published a textually verified version of the novel, based on manuscripts and a typescript from 1963.

In 2014, the main text of the novel was published as part of a complete collection of drafts, based on more than 10 years of studying archival materials. This textual work, prepared by E. Yu. Kolysheva, with a volume of more than 1,600 pages, made it possible to more accurately reconstruct the author's intent and eliminate many contradictions in previous editions.

Thus, the path of the novel The Master and Margarita to the reader took almost 30 years and was accompanied by numerous editions, censorship restrictions and textual disputes. Today, the novel is recognized as one of the most important works of Russian literature of the 20th century. And the phrase “Manuscripts do not burn” from the book has become a catchphrase and symbolizes the indestructibility of creativity.

Restless novel

After the death of Mikhail Bulgakov in 1940, the exclusive copyright to his works, including the novel The Master and Margarita, passed to his widow Yelena Shilovskaya. In 1939, Bulgakov made a will in which he appointed Yelena as his sole heir. After her death, the rights were inherited by her descendants from a previous marriage — Sergei Shilovsky and Darya Shilovskaya (non-blood relatives of Bulgakov, which outraged representatives of the Union of Writers of Russia). According to Russian law, copyright is valid for 70 years after the first publication of a work, starting from 1 January of the year following publication. Since The Master and Margarita was first published in 1966, the rights to it remain in effect until 2037. Thus, the heirs continue to control the use of the novel, including its film adaptations and reprints. The issue of Bulgakov's legacy has arisen before. For example, Mikhail Rodionov, head of the copyright department of the law firm Uskov and Partners (editor’s note: he held this position at the time of the interview), told Honest Correspondentoutlet on 15 March 2010 about the nuances of copyright in relation to the novel The Master and Margarita:

“Bulgakov died in 1940. Previously, we had a law on a 50-year term of copyright protection. And there is a transitional provision: if previously the established 50-year term expired by 1 January 1993, then the 70-year term does not apply. Based on this provision, the general term of Bulgakov's copyright protection expired almost 20 years ago. However, for example, the novel The Master and Margarita was published in 1966-1967. In relation to this work, the provision of Article 1281, paragraph 3 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation applies, according to which, when a work is made public after the death of the author, the term of legal protection is calculated from 1 January of the year following the year of publication of the work.”

In this interview, Rodionov emphasized that it is necessary to “establish encyclopaedically precisely when each work was published.” It is from this date that the term of copyright protection is calculated. At the same time, works that were published during Bulgakov's lifetime, for example The Days of the Turbins, have long had the status of public domain. In 2017, the Russian company Mars Media Entertainment acquired the rights to film the novel from Bulgakov's heirs, the Shilovskys. However, it turned out that the same rights had previously been sold to American producer Michael Lang, which led to a lawsuit for 115 million rubles. This case sparked a public discussion of the legitimacy of the Shilovskys' claims to Bulgakov's copyright.

A “retrospective” look at the law

Grigory Ivliev, while examining the situation with copyright, latched onto two points. The fact that the Shilovskys are Bulgakov's non-blood relatives, and, in Ivliev's opinion, this is a reason to deprive them of their rights, despite the current legislation of the Russian Federation. He also suggested looking at the legislation “retrospectively.” That is, to start not from the laws in force in 2025, but from the laws that were in force at the time of Mikhail Bulgakov's death, the first publication of the novel, and subsequent changes in copyright legislation. Ivliev's logic led to the fact that, in his opinion, the copyright for The Master and Margarita had long expired, and Mikhail Bulgakov's novel should be recognized as public domain.

Grigory Ivliev sees the situation this way: in 1939, Bulgakov made a will, transferring all rights to his wife Yelena. At that time, the decree of the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR of 16 May 1928 On Copyright was in effect. This document determined the term of copyright protection — 15 years after the death of the author. Bulgakov died in 1940, which means that, according to the law in effect at the time, all of his works, regardless of whether they were published or not, entered the public domain on 1 January 1955.

“This is arithmetic. They counted from 1 January of the year the author died. That is, the writer's rights were subject to protection until the end of 1954. From 1 January 1955, they entered the public domain,” Ivliev emphasized.

He clarified: the fact that The Master and Margarita was first published in 1966-1967, after the death of Bulgakov and Yelena, does not change the matter. According to Ivliev, at the time of publication, the novel did not fall under copyright protection, since the protection period had already expired. “By that time, Elena Bulgakova no longer had exclusive rights to the work,” Ivliev added. The modern heirs — the grandson and great-granddaughter of Yelena Shilovskaya — refer to the current Part 4 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation, which came into force on 1 January 2008. According to Article 1281, exclusive rights to works first published after the death of the author are protected for 70 years from the date of publication. That is, under current legislation, the rights to the novel are protected until 2037.

However, Ivliev argues that such an interpretation is legally erroneous. The key document here is not only Part 4 of the Civil Code itself, but also the Law on its implementation. In particular, Article 6 of this law states: the 70-year term applies only to those works for which the 50-year term of protection had not yet expired by 1 January 1993. And Bulgakov died in 1940, that is, his copyright, even under a more lenient law, expired by 1990.

“What was in the law of the Russian Federation of 1992? The term was 15 years, then it became 25 years, then 50. But it was clearly written: [this term] applies only to those works whose protection term had not expired by January 1, 1993. And Bulgakov's expired long before that,” said Ivliev. And this contradicts the words of lawyer Rodionov, who commented on the situation with the rights to the novel The Master and Margarita back in 2010.

Ivliev emphasized: the heirs, referring to modern legislation, ignore the fact that legal relations with Bulgakov's works began long before the adoption of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation and therefore should be assessed in the context of previous legislation.

“When they make such a statement, the legal regulation applicable to the legal relationship in question is not taken into account. The current norms are taken immediately, without taking into account what has been happening with Bulgakov’s legacy all these years,” Grigory Ivliev emphasized.

This problem has become the motive for which Bogomolov wrote the letter to Medinsky. The director cannot use the novel The Master and Margarita to stage a play based on it without paying for the assignment of copyright. “The situation is aggravated by the fact that the use of Bulgakov's works is extremely difficult, which causes discontent in the creative community as a whole,” said Ivliev.

This begs the question: why shouldn't Konstantin Bogomolov do the same as other cultural figures who ask permission from heirs, enter into contracts and pay money for the assignment of copyright? This mechanism has been working in our country for over 30 years. And yes, there are cases when heirs are against the publication or use of a work. This is their right as heirs and owners of intangible assets. In this case, everyone is waiting for the status to change and the work to become public domain.

In the 1990s, Stas Namin, who was present at the press conference with Milos Forman and Hollywood actors, including DiCaprio and De Niro, attempted to film the novel. The project fell through because the heirs had already sold the copyright to the film adaptation.

“It turned out that the rights belonged to some young man (editor's note: Namin was referring to Yelena Bulgakova's grandson, Sergei Shilovsky), who had already sold them to three different companies. And as soon as one of them tried to do something, the other two would sue it,” Namin complained.

According to Ivliev, the legal impasse can only be resolved with the involvement of the professional community and public expertise. “The result of this study for us is the conclusion that Bulgakov's works are in the public domain. They are open for use, and regulation of this position corresponds to the demands of society,” he concluded. It is unclear why Ivliev decided that outdated laws should prevail over current legislation. But it is obvious that if these initiatives are given a go, then we can come not even to even greater confusion, but to legal chaos.

Ekaterina Petrova is a book reviewer of Realnoe Vremya online newspaper, the author of Poppy Seed Muffins Telegram channel.