''It will be easierf if at least 30% of the population realises waste needs to be sorted''

How Switzerland came to ecological lifestyle and taught the population to look at their own skips

During the trip of journalists to Switzerland organised by AGC-2, Realnoe Vremya's correspondent managed to get acquainted with waste sorting culture and the experience of the country that didn't know what to do with tonnes of residues but had found them a useful application for almost 30 years. Realnoe Vremya tells how the citizens were taught to separate plastic from card and pay for special rubbish bags.

Waste sorting as lifestyle

During the press tour to Switzerland, we managed to get acquainted with not only the waste incineration plant near Lucerne but also the way people treat residues. And we can only envy this way. There is just a million of rubbish bins across the city in Zurich – there are separate bins 5-6 colours for glass bottles, metal cans, card. Batteries, bulbs and other more dangerous and rare waste can be left near supermarkets. In general, when walking in the city, there can be found bins for almost everything. For instance, public toilets in the centre have a unit for… syringes.

Bags to collect dogs' faecal matters are especially surprising – a dog painted directly on rubbish bins severely looks at you from a special department. If you take this bag, you can see even a schematic instruction on how to collect your pet's waste material. The bags are free, and the very citizens use them actively and attach it to a lead while the dog is doing its business.

Local resident Florentina is a 25-year-old young woman says now she can't already imagine how all rubbish can be piled altogether. Having gone once on a holiday to Italy, she saw the country's locals unceremoniously mixed all residues, she was literally round-eyed – in Switzerland, such an attitude to rubbish is just unacceptable.

30-year road

Switzerland isn't a big country by Russian standards. 8,3 million people live on its territory officially. There wasn't any legal regulation for waste management before 1973, as a result of which landfills polluted rivers, underground waters and the air, of course. Waste had being buried by that moment. But the plants were far from being perfect and also polluted the air. The situation began to change in 1986 when authorities decided to deal with this issue closely. According to them, the whole work linked with waste was to be based on legal requirements designed to protect people and the environment. In addition, all residue treatment systems needed to be ecologically compatible, while Switzerland needed to get rid of all waste on its territory. In the end, according to ruling principles, only two products should leave after treating residues: recycled substances and residues for storage. Landfills were officially prohibited in 2000. So all the above-mentioned things needed to correspond to two ideas: not to hand over the problems to future generations and other countries. In fact, we can say 30 years later the Swiss got an A for having fulfilled the tasks.

Now cantons must provide disposal of solid municipal waste legally. They, in turn, re-charge communes with these obligations, that's to say, local governments. Local management offices and commercial companies give them non-recyclable waste. Mixed solid waste is collected in Switzerland by communes, municipalities or private companies working on behalf of local governments.

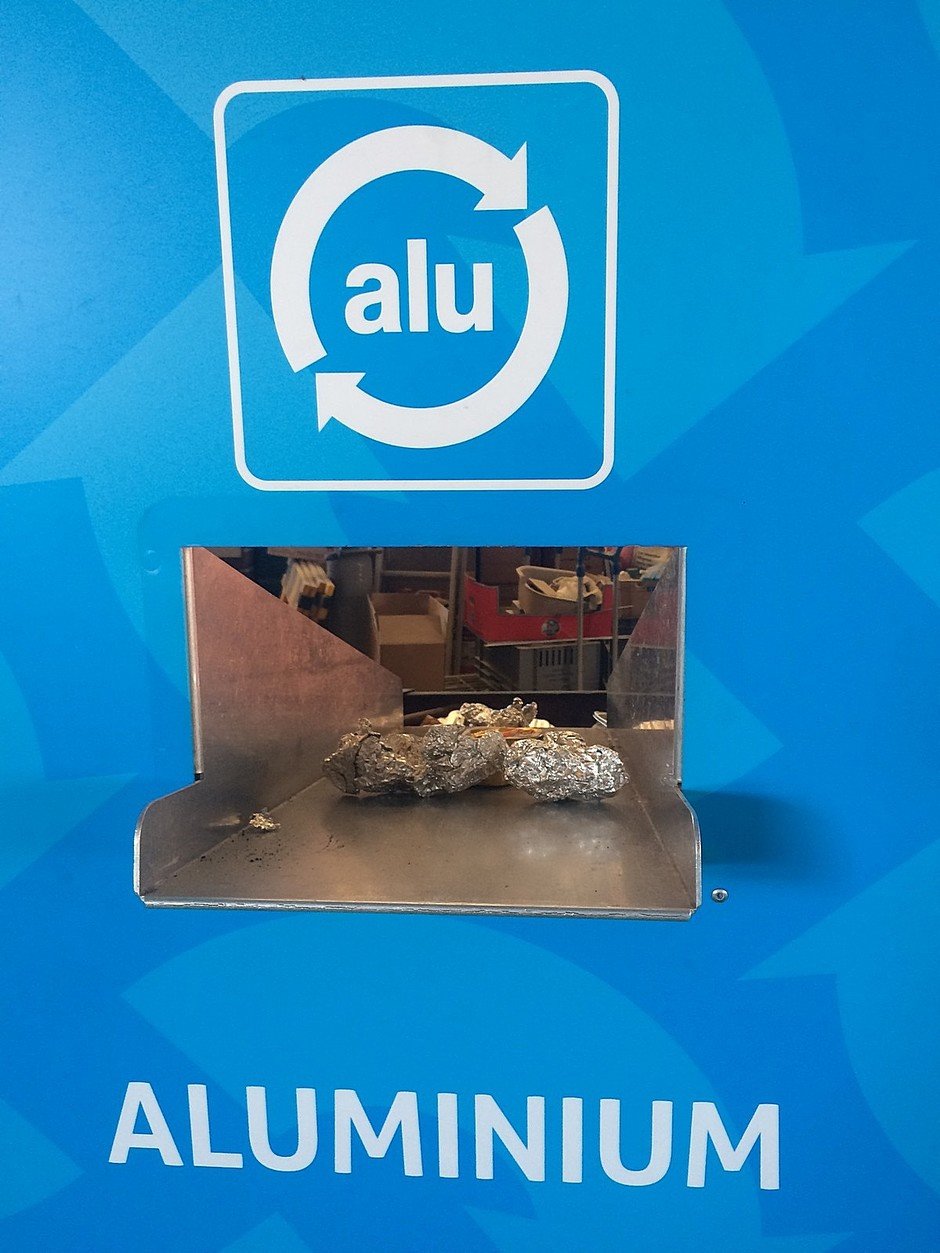

Both communes and department stores collect waste for recycling, skips for different fractions of waste stand next to them.

How 'polluter' started to pay

Careful residue sorting for recycling allows to avoid expensive mixed waste sorting – it's precisely what Russia starts to aspire to now. In 2014, this allowed to recycle over 53% of all residues. For instance, paper and card are 90% recyclable after consumption, glass – 95%, PET bottles – 82%, aluminium cans for drinks – 92%, batteries – 71%. In general, 355,1 kg of waste per capita is recycled, and 353 kg are burnt.

Collection and transportation of a tonne of waste cost about 100 Swiss francs. Prices are much lower in urban districts than in the countryside. Combustion is around 100-180 Swiss francs per tonne, while an average fee for waste import is equal to 142 Swiss francs per tonne. These sums annually fall because most factories have been working for less than 10 years, their capital costs reduce by this time, loans taken out to build enterprises pay back, and the majority of incineration plants has a full load and operates almost nonstop.

If earlier the costs spent to dispose waste were financed by public subsidies, income tax and basic tariff depending on the number of rooms in a flat. Later Switzerland switched to the principle ''the polluter pays''. Now the budget consists of the basic tariff and payment per weight or volume of supplied waste. In other words, there is a tax per bag of waste: a 5-kg bag costs 1,5-2 Swiss francs, a 60-litre bag is 3,80 Swiss francs. They are put next to the house, then a truck comes and takes all waste.

From bitumen to CDs

During the press tour, we visited a big sorting centre Schmid AG, which is 20 km far from Zurich. The enterprise has been operating for 13 years and is a family business – Prisca and Alfred Schmid run it, while their son Silvio helps them. The plant accepts all types of municipal waste, including dangerous. Any person can bring residues here. The most interesting thing here is that there are no unpleasant smells like in the WIP – biological residues don't go to the plant, other companies deal with them.

Having seen people daily come with huge rubbish bags, take little children whom they place onto the bins and allow them to throw a part of the waste, the journalists rushed towards Prisca to ask whether they paid the locals for this waste. The plant's head was first confused at the question, but then it made her laugh. It turned out people gather at the own will and go to the countryside early in the morning to get rid of residues. And the benefit is here there is no necessity to purchase special rubbish bags.

There are skips to anybody's liking. With bottles and paper all is clear. But where can one see sections for CDs, coffee, foil and other small rubbish? Tetra Pak containers are also collected separately. This waste is recycled to produce packing board.

''They aren't collected in Switzerland, but we do collect, it's our peculiarity,'' says Prisca Schmid.

Electronic devices can also be brought here. Costs on their disposal, by the way, are included in a purchase's price. Special organisations collect them, and sorting centres get them after giving them to other companies for recycling, depending on the quantity of waste, payment for their services. If one is lazy to bring, for example, a fridge to the centre, it can be left in any shop. In this case, they will do it for you, as you already paid for this service.

What's more, people have to pay for a part of the waste in the centre itself, for instance, for old furniture. So if a person brought a sofa, it's weighed first and given a price. One kilogramme of such waste costs about 39 Swiss centimes.

Apart from natural persons, commercial companies can bring their waste to Schmid AG, but they pay for waste disposal. Non-sorted residues are accepted for a higher price than the sorted ones. They can bring even bitumen to the centre, which is ground right there and sold to construction companies that use it to lay roads. They also sort metal and sell it later – the locals are already paid for this if its volume exceeds 20 tonnes.

The enterprise is glad about copper most, as prices for it are high. Chemicals such as pipeline detergents are the most unprofitable waste.

Schmid AG competes with other companies not only from this region but also from other cantons

This sorting centre is one of the biggest in the district. There are other centres, but they accept only some types of waste and work several times a week. And Schmid is open from Monday to Friday from 7.30 to 11.45 with one 30-minute break and from 13.00 to 17.00. On Sundays, the enterprise is open from 9 to 11.45, it's when they receive most waste. About 800 cars bring residues for three hours, though there were just 50 cars when they just opened. In 2017, they received 234 tonnes of green glass only, white glass was equal to 168 tonnes, brown glass – 90 tonnes, card – almost 500 tonnes.

They take the waste that was already sorted to recycling centres, which are also located in Switzerland.

According to Prisca Schmid, they started to run the family business with collecting waste in the homestead, expanded and opened a big sorting centre in 2005. It turned out this business wasn't very easy – the competition in the region is very high. This is why nobody rakes in it.

The sorting centre's head says they compete with other companies not only from this region but also from other cantons. For instance, now we go to Lucerne, and the companies from there become their rivals. They come to them and also take waste, moreover, for lower prices. It's a problem.

She notes rivals have lower expenses because they hire drivers from Poland and the Czech Republic who are ready to work for a lower salary.

Schmid AG itself constantly needs space. As a result, they also need to optimise processes. For instance, they've recently bought a new plant to press aluminium bottles for 250 million Swiss francs, which allows to pack waste more compactly and carefully by saving money for its storage and disposal.

Social control and fines as extreme measure

One of the main questions Realnoe Vremya's correspondent was interested in was about the ways of inculcating the culture of waste treatment in the locals. PhD, former head of the Waste Management Administration in the Federal Environmental Protection Agency Hans Peter Farni shared his own experience in working in this field. According to the newspaper's interlocutor, some people rapidly realised it's necessary to care about waste, for others, it took years.

Hans Peter Farni noted that it will be easier if at least 20-30% of the population realises, and you will assure them waste needs to be sorted because there will be social control. So he says it's very important.

But it should be taken into consideration that Switzerland didn't limit to only a social control while teaching people to sort waste. People can pay a fine of 50 to 200 Swiss francs for throwing rubbish without a deliberately bought bag. The lawbreakers can be found with a CCTV camera or the rubbish itself if they see a newspaper or a letter with their address. It seems that it's very complicated to find a lawbreaker, in fact, but Realnoe Vremya's journalist saw a real example of how Switzerland learnt to find such people: the interpreter who accompanied our delegation told once she had to pay 150 Swiss francs for such a reckless step.

The settlement's administration controls how the population treats waste. But, according to Hans Peter Farni, authorities don't have a goal of collecting as many fines as possible.

The former ecology functionary says the most important thing is to ask and understand this person, why he did so. Is it better for ecology, is it expensive? Or what's wrong?

Moreover, if there are fines because of no bags, there isn't any for non-sorted waste. The fault is on the polluter's conscience. Same Zurich has a very high level of social control – cans or bags can be found on the road, of course. But you more often come across people who gently sort bottles in colourful skips and stope card.