Superman — the first migrant

How comics explore changing countries of residence, otherness, and adaptation

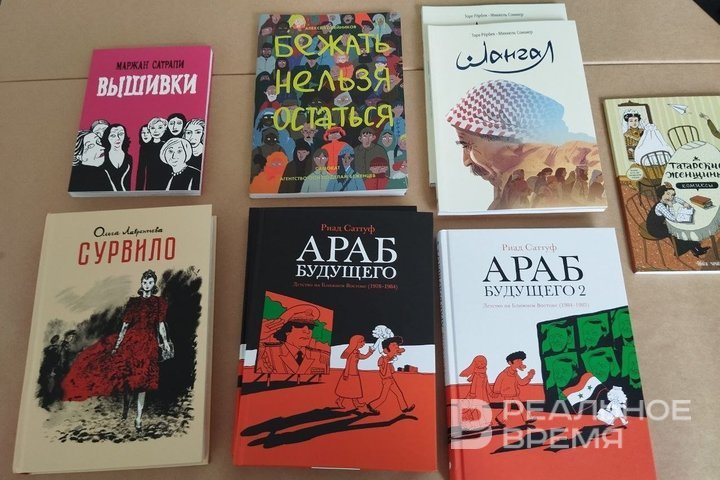

A series of events for the Point of Relocation project, timed to coincide with World Refugee Day, has concluded in Moscow. Among the workshops, walks, discussions, and art mediations, there was also a lecture titled “On Migration Through Comics and Graphic Novels”, delivered by Radif Kashapov, deputy editor-in-chief of Realnoe Vremya online newspaper, and his wife, Regina Gayazova, curator of the Tatar Comics project.

Krypton — my planet

The Point of Relocation project is organised by the UN Refugee Agency, Garage Museum, and Moscow Museum. As part of the project, for example, in 2021, a performance-installation titled Rohingya by Kazan director Tufan Imamutdinov was shown. Our lecture took place in a communal block of the Narkomfin Building. We hope that the main Tatarstan monument of constructivism — the Mergasov House — will one day look just as fascinating.

Comics encompass stories about superheroes, multi-page dramas, and reinterpretations of literary classics. They are also a tool for discussing migration, the loss of home, the awareness of one’s own and others’ otherness, and working with family history.

Such comics are published both in foreign languages and in Russian (mostly translations). Even the multifaceted saga of Superman is a migrant story. He arrived from his home planet Krypton, sent to Earth by his scientist father just minutes before its destruction, where a farming family took him in and gave him the new name Clark Kent.

Comics are not only accessible to a wide audience because their illustrations allow them to be understood even without knowledge of the language. For example, Sean Tan’s book The Arrival contains no text at all, only images. Through comics, the inexpressible can be conveyed — trauma, nostalgia, dislocation, the hero’s inner state. To “show” one’s existence to the reader. And for the author, it is a form of art therapy.

Through the eyes of a child

In numerous books on migration, authors speak about the reasons for moving — ranging from professional to political, about the loss of home, the difficulty of perceiving the “foreign,” one’s own “otherness,” and adaptation. They also discuss how the importance of family history and preserving ancestral ties grows during this time. After the lecture, I would add one more important theme — the story of those who remained “there.”

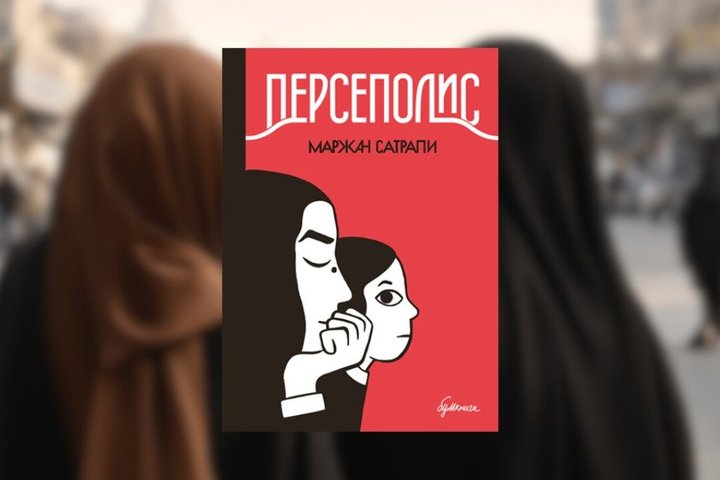

The most famous books about migration speak not only about this experience. Marjane Satrapi, author of Persepolis, said: “The story of a girl growing up in Tehran and then leaving is told in the first film not for the sake of autobiography: I used my own life circumstances to talk about what was happening in Iran at that time.” Through the depiction of Satrapi’s childhood and adolescence, we see the 1979 Iranian Revolution from a different perspective.

The Arab of the Futureby Riad Sattouf portrays a panorama of the Middle East in the 1980s: “...about a childhood spent in Libya, Syria, and France under the shadow of three dictators — Muammar Gaddafi, Hafez al-Assad, and his own father.” Like Satrapi, Sattouf works actively with contrast. Here is abundant Europe, there is impoverished Libya. Yet in both places, the protagonists cannot find their place.

At times, the narrative takes a darker turn: Shangalby Tore Reberk and Mikkel Sommer tells the story of the conflict between terrorists and the Yazidis, a religious minority in Kurdistan, who are forced to flee to Mount Shangal, their only refuge for several centuries.

As for Russian authors, one of these books was published by the UN Refugee Agency with the support of the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. It is Run Refugee Stay by Alexey Oleynikov, which describes the experiences of Russian schoolchildren originating from Yemen, Afghanistan, South Sudan, the Central African Republic, Palestine, Syria, and Congo. The saddest stories are about children born in Russia who have not yet become fully integrated: they continue to adapt and have much to share about language barriers, bullying, and poverty.

Does the post-Soviet world speak about this?

From the audience came the question: are there books about the migration experience from post-Soviet countries, from the regions to Moscow? In film and theatre, this topic is already discussed quite actively (recall the film Ayka about a Kyrgyz illegal immigrant, which made the shortlist for the Oscar in the Best International Feature Film category). In comics, however, this is rarely addressed.

Midnight Land by Yulia Nikitina describes her move from Salekhard to St. Petersburg: it is a story of parting with childhood, loneliness, and the struggle for the right to pursue one’s passion. In general, it is worth checking out Nikitina’s social media accounts — she tells much of her lived experience through comics.

Many books describing the immigrant experience have not been translated into Russian. Let’s take a few examples at random. Welcome to the New Worldby Jake Halpern and Michael Sloan began as a series of newspaper comics about Syrian refugees arriving in the US in 2016. Later, the authors retold the same story from the perspective of children.

Pashmina by Nidhi Chanani tells the story of a young Indian-American woman who has never been to her mother’s homeland. The only reminder of the country is a pashmina shawl. A film adaptation was planned but later cancelled.

Undocumented: The Worker’s Struggle is a novel by Duncan Tonatiuh, an American of Mexican descent, telling the story of Juan, an immigrant who arrived in the US illegally.

Soviet Daughter: A Graphic Revolutionby Yulia Alekseeva tells the story of the author’s grandmother, a Jewish woman who survived the revolution, genocide, and migration, and worked as a secretary for the NKVD and a lieutenant in the Red Army. It also shares Yulia’s own experience living in Chicago.

Finally, Almost American Girl is the story of how Chuna Ha became Robin Ha, moving to the US from South Korea with her mother: now she has a stepfather, a new language, and a new name.

The Duality of the Tatar World

Tatar comics, of course, depict the migration experience from a unique perspective. Even the inhabitants of the otherworld, spirits, in Tatar mythology are called “ияләр” (iyälär), derived from the verb “ияләшергә” (iyäläşergä), meaning “to adapt” or “to get used to.” Kazan itself is a melting pot of cultures. Kazan is Tukay and Gorky, Mardjani and Ilminsky, Aksakov and Iskhaki. Therefore, the experience of Maksim Alekseevich, described in the collection Kazan Stories, is a migrant experience. The young writer arrives in the city in search of himself and, through a traumatic journey, eventually creates 26 works.

The world of a Tatar person is inherently dual. They speak two languages and carry a Soviet-Russian background intertwined with a distinct Tatar mentality. For example, Fatikha and Suleyman Aitovs, preparing in the early 20th century to open the first secular school for girls in Kazan, studied European educational models and effortlessly translated from Arabic, Persian, Russian, English, and French. Lacking their own base at the time, they confidently adopted others’ knowledge and made it their own.

The Tatar hero is constantly in a state of adaptation. This is especially evident at the beginning of the last century. Here is the story of the first Tatar actress, Sahibjamal Gizzatullina-Volzhskaya: when she steps onto the stage, it provokes protests not only from the conservative clergy. The local authorities also forbid performances in Tatar cities. The life of the progressive Muslim woman is constantly under threat (she was even shot at!).

Moscow and St. Petersburg are an important part of the Tatar world. On one hand, these cities have long been places of Tatar settlement. They are also places where many heroes of our world receive their education. On the other hand, after being dismissed from the opera theatre, Sara Sadykova receives her first recognition in Tashkent. This is because Tatars are dispersed around the world. In this case, the question of what migration means becomes more complex. After all, when moving, a person always looks for their own.

In particular, the collection Мәхәббәт / Lovedescribes the story of Ismail Gasprinsky and Zukhra Akchurina. Together, they publish the newspaper Tardzheman. It is written in Russian and deliberately simplified Tatar — but intended for Muslims. This is no longer tied to nationality or territory, but to religion. Therefore, Tardzheman is received by people from Egypt to Siberia.

This means that Kazan, which proclaims its diversity, needs to articulate it not only in tourist brochures but also at the level of literature, painting, and comics. This provides an opportunity to comprehend painful themes, which will simultaneously serve as psychotherapy and a means of self-discovery, allowing one to view complex situations from different perspectives and find new meanings in them.