Square with a hole: How V–A–C Sreda reassembles culture

From a missing car to LA Pirates’ records: The Journey of Creating 'V–A–C Sreda 2: Outlook’

Flexi discs are no longer produced, the old technologies are lost, and Soviet-era machines have vanished. So how was it possible to recreate the legendary format of the Soviet magazine Krugozor? A true detective chronicle unfolds: the search for rare technology, correspondence with a craftsman in Crimea and the “Pirates” of Los Angeles, the tense wait for a shipment at the border, and finally, assembling the book by hand. At the Center for Contemporary Culture Smena, Daniil Beltsov, the editor-in-chief of V–A–C Sreda and senior editor of V–A–C Press, shared how all obstacles were overcome — and why Krugozor is not just a book but a true work of contemporary art.

Flexible records and cultural dialogue

The editorial team of V–A–C Sreda has always explored new ways of working with text, imagery, and sound. Born in the digital sphere, the project launched four years ago with a foundation built on three key formats: “read," “watch," and “listen.” Texts, artistic works, and podcasts became its defining pillars. However, the online space eventually proved insufficient. In 2023, the team decided to step into the physical world, releasing V–A–C Sreda 1: Gran’— a collection of conversations with authors and artists. The edition sold out within three to four months, demonstrating a clear audience interest in tactile media through its innovative book-newspaper format.

The second installment of the project, V–A–C Sreda 2: Krugozor, began with an unexpected discovery. Editor-in-chief Daniil Beltsov stumbled upon the existence of the Soviet magazine Krugozor, which was published from 1964 to 1992. What set it apart was its inclusion of flexible vinyl records — audio supplements that could be played on a turntable. This idea immediately captured his imagination. “I was born in 1997 and had never encountered anything like this. It seemed like some kind of Soviet technological magic,” Beltsov recalled. A second-hand copy purchased on Avito for 400 rubles became the starting point for a deeper exploration into this forgotten format.

The pivotal moment came when Daniil Beltsov visited his hometown and shared his discovery with his parents. “Our basement is full of Krugozor magazines," his mother told him. This contrast in perception — novelty for the V–A–C Sreda team versus nostalgia for the older generation — became the foundation of the project. The editorial team became fascinated by the idea of reviving flexible vinyl records, but the question remained: What should be on them? Initially, Beltsov imagined an “archaeology of Soviet pop music,"exploring the popular culture of the 1960s and finding common ground between generations. “For example, I only listen to Russian rap, while my friends don’t even consider it a genre. Where is the intersection?” he pondered. The answer lay in universally recognized hits — songs like Malinkiand Sedaya Noch — music that unites people across time.

However, as discussions evolved, the project expanded beyond music. V–A–C Sreda 2: Krugozor became a media experiment — combining flexible vinyl, text, and visual imagery. It was an attempt to create a format where sound, words, and images function as a unified whole.

Three musical eras

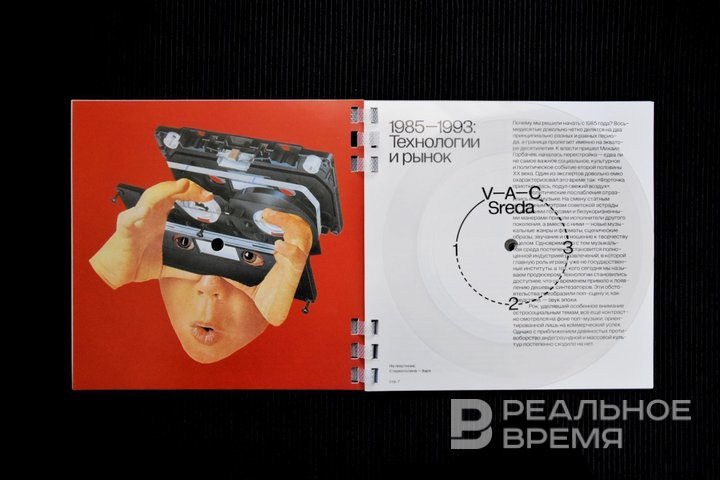

Initially, five musical periods were planned, but there were three of them. “I'm not a music critic or a music expert," Daniil Beltsov said. This fact became the starting point. So, we need someone who can test hypotheses and propose new optics. The choice fell on Anton Vagin, a musician and administrator of the public “Any good pop music”. When Baltsov showed the Vagina to the foreground, the reaction was unequivocal: “Dan, you're doing great, of course, but it's not like that at all.” As a result, the number of musical eras was reduced from five to three. “The scope of the Horizon simply did not allow us to cover five epochs. There is too much information," explained Baltsov. We settled on three periods:

- 1985-1993 — “Technologies and the market”. This is the perestroika period, affordable Western technologies, the first cheap synthesizers. At the same time, groups appeared that created music from the position of “I can do that too.”

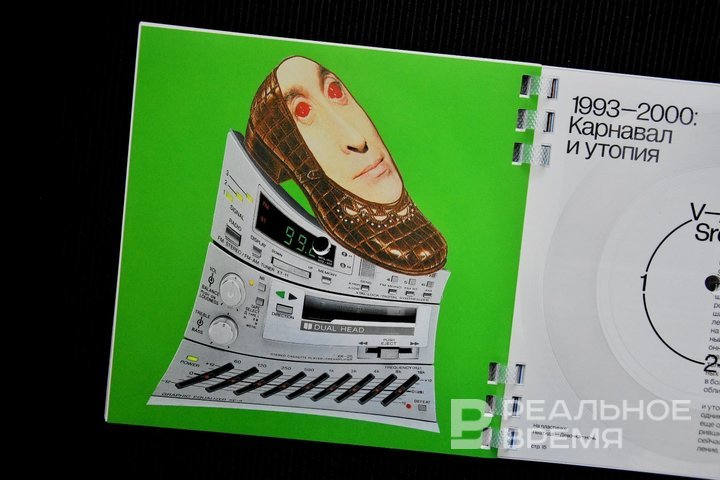

- 1993-2000 — “Carnival and Utopia”. The days of raves, punks, rockers, pop stars like Shura. The name of the block was taken from a text by Lev Danilkin about the 1990s, which were a time of complete experiment.

- 2000-2008 — “Sparks and Illusions”. The period in which the influence of the Ranetki group became decisive. “It's a cultural code. Without this context, it is difficult to understand modern performers: Dora, Monetochka (recognized by the Ministry of Justice as a foreign agent) and others," said Beltsov.

The first idea is three large analytical texts of 20,000 characters each. However, it soon became clear that the book's “playful” format required a different approach. This created a structure with different types of participants: witnesses (people who worked in the industry) and experts (music journalists, critics). Baltsov described the process as follows: “We selected a long list of speakers, then narrowed it down to eight people. We conducted in-depth interviews with each of them. The output is about 60 thousand decryption characters. The book includes about 1 thousand.”

Among the witnesses are Vladimir Miklosic, the founder of the A Studio group, and Alexander Kushnir, the producer of Mumiy Troll. Among the experts are Yuri Saprykin, Nikolai Redkin, Anton Vagin. The questions concerned not only genre characteristics, but also the general cultural context. At the same time, the dialogues often went in an unexpected direction. “Usually, our editorial colleagues started with questions about the genres of Russian pop, and then the conversation unfolded by itself," added Beltsov.

The key challenge is to reduce the amount of information and build a coherent narrative. “It was important that the remarks of the speakers formed a single story. It's not just a set of interviews, it's a whole drama," Daniel explained. The project was launched on August 29, 2024, and everything was ready on September 13. Although such projects usually take five months, the involvement of the team has worked here. “We worked 20 hours a day," said Baltsov.

The visual language of new Krugozor

Illustrations in Krugozor have always been important. This is not just a text accompaniment, but an independent layer of meanings. But there wasn't enough time to create a visual sequence. Therefore, Beltsov called the fashion designer Roma Uvarov.

“Roma, I need 20 illustrations," he said. “Okay,” Uvarov replied. “Five days," added Baltsov. “What? Five days?!” However, the argument was weighty: “The fee is very large.” That's how a man appeared who created 20 collages from scratch in a week.”

Before starting work, Baltsov and Uvarov compiled a keyword cloud. It was necessary to rethink the Soviet visual code, but at the same time maintain recognition. Uvarov, who had not worked with this context before, literally immersed himself in it. The result exceeded expectations: “When he [Uvarov] sent me the pictures seven days later, I sat and thought, wow, this is speed, of course," Daniil Beltsov added.

When the collages were ready, the question arose: how would they interact with the texts? Baltsov found the solution in a tactile experiment: “Armed with scissors, glue and pencils, I made the first prototype. In the publishing world, this is called a “doll”. Daniel took the original “Horizon”, pasted it with paper and manually arranged the illustrations. The pictures moved, the texts rearranged, creating a new rhythm of narration. It was a process in which the physical layout anticipated the digital layout. An unconventional approach allowed us to understand how the visual series can be combined with the content, where accents are needed, and where pauses are needed. This is how the final structure of the book took shape.

From Crimea to LA

Flexible plates are a key element of the concept. But what should I write on them? Initially, the idea was for modern artists to rethink the past. But then it came to an understanding: records should sound like the music of their time, but at the same time remain relevant. To find the right tracks, the editors turned to Anton Vagin again. He compiled a long list of 50 performers in a day. The main criterion is that the song should sound so that it can be confused with the music of the past.

The first record is the song “Zarya” by Kazan singer Stereopolina. Her synthesizer sound perfectly conveys the era of 1985-1993. The second record is “Girl—night” by Neathida, it's a one hundred percent rave of the 1990s. And the third is “Late” by the singer “Forget it, Lerochka” from Irkutsk, a modern pop-rock composition that echoes the “Ranetki”. So, unexpectedly, another hidden dialogue appeared in the project: only men are among the speakers, and only girls sound on the records. “I think it's a funny contrast," said Beltsov.

When it seemed that everything was assembled, the texts were ready, the layouts were made, the main question arose: how to make flexible plates? It turned out that production in Russia had stopped back in 1992, and the technology had practically disappeared. I had to look for workarounds — through YouTube, Avito, and unexpected contacts in different parts of the world. When the search began, it turned out that there are only two places in the world where flexible plates are still being cut. The first point is a craftsman from Crimea. He works alone and cuts vinyl piece by piece in his spare time from his main job. When he found out that 900 copies were needed, he immediately refused: “It's three years to cut! Are you crazy?” The second point turned out to be even more unexpected — Los Angeles. There is a company with the telling name “Pirates”.

The communication process felt surreal: on one side, a chat on Avito with a craftsman in Crimea; on the other, correspondence with American Pirates. It soon became clear that the Pirates didn’t produce records themselves—their machine was based in the Czech Republic. The logistics chain stretched across multiple countries: Los Angeles relayed orders to the Czech Republic, from where the records were shipped to Russia via the Baltic states and Belarus.

The shipment was expected to arrive in Moscow on December 24, the day of the presentation. But three days prior, the records got stuck at the border. Two boxes made it through, but the third one didn’t. Since each box contained a different record, this meant the edition couldn’t be assembled without the missing piece. The presentation was in jeopardy—chairs were set, the audience was waiting, but the books weren’t there. Then, on the evening of December 23, the first sample copy arrived at the office. They placed it on the turntable immediately. It played.

The “Krugozor” edition arrived in boxes, but unsealed. Each copy was hand-numbered—1 of 300, 2 of 300, 3 of 300, and so on. All 300 of them. Beltsov recalled: “I picked up a copy at 'Smena' and randomly opened number 18 out of 300. I remember struggling to write the number eight neatly, and here it looked just as crooked.” By the way, there won’t be a reprint. Only 300 copies exist. In Kazan, not a single one remains.

The records were pressed in the Czech Republic, while the booklet was produced in Russia. The biggest challenge turned out to be finding the right fastenings. The solution came unexpectedly — a plastic mouse pad. It was cut into strips and used as a binding element. In the end, everything came together: the records played, the booklet folded perfectly, and Krugozor became the very artifact it was meant to be from the start.

Collages by Roma Uvarov, quotes, three records — Krugozor became a multi-layered object that unfolds gradually. It’s not just a book but an experience where sound, text, and visuals create a new narrative. The first copies sold out instantly. Reflecting on why such a book is needed at all, Beltsov remarked that projects like this must exist—because these books become works of contemporary art.

Ekaterina Petrova is a literary columnist for Realnoe Vremya online newspaper, the author of the telegram channel Buns with Poppy Seeds.