''Such food was considered unclean, and the Tatars looked with disgust at those who ate the mushrooms''

Tatar cuisine: history and modernity. Part 2

Three weeks left until the New Year and the hostesses are already thinking of what eats to put on the holiday table. Obviously, many of the Tatarstan citizens are going to prepare traditional Tatar dishes. A Kazan anthropologist and columnist of Realnoe Vremya Dina Gatina-Shafikova continues to acquaint the readers with the evolution of the Tatar cuisine. In today's column, she tells how they drink the Tatar tea, whether the people consumed the mushrooms and when the Tatars started to eat tomatoes.

What is it – the Tatar tea?

Honey as a sweet treat was common because the Tatars have harvested wild honey from ancient times. It was served with tea, used for beverages and as an ingredient for cooking pastry. Although, of course, by the beginning of the 20th century it was supplanted by sugar, which was used both separately and as a sweetening in cooking.

The Tatars have a special attitude to the sweets. The dried fruits were almost always on the table, as well as sweet pastries, with tea, which were also very loved. As N.I.Vorobyev noted, ''the most common drink among the Tatars of all classes is tea… especially among the peasants, they drink often and a lot. They drink pekoe tea, and brick tea (low quality of Chinese tea, pressed into tiles similar to the bricks — editor's note). The poor often drink tea substitutes, such as dried raspberries, currant leaf, leaf fireweed, etc. The tea is brewed very thick and is consumed strong and hot mixed with milk or with honey or lumps of sugar. Tea is the first Tatar treat for the guests.''

Unclean mushrooms and healthy food

In general, the Tatars had a positive attitude to the plants. Often herbs (oregano, raspberries, lime blossom, etc.) and roots were used in folk medicine. For example, in the paper of 1927 Food of the Kazan Tatars describes the benefits of eating the herbs ''to cleanse the stomach'' and ''for the expulsion of worms'' and ''to prevent rheumatism''.

Despite the fact that neighbouring peoples utilised mushrooms as food, the Tatars had more a negative than positive attitude towards mushrooms. As well as some other authors, Liliya Gabdrafikova in the article devoted to the food culture of urban Tatars at the end of 19 th century-beginning of the 20th century wrote that ''such food was considered unclean and the Tatars looked with disgust at those who were eating mushrooms''. In the story by Gayaz Iskhaki He still was not married, the protagonist Shamsi tastes dishes with mushrooms cooked by his Russian cohabiter woman. The young man had conflicting emotions: on the one hand, it was very delicious, but on the other hand, this food was kind of prohibited. The Tatars started to pick mushrooms, to conserve them, and to cook only in the second half of the 20th century. Before, it had not been accepted to eat that product among the Tatars.

Outlandish tomatoes and pickled watermelons

The vegetables were least used in the daily diet of the Tatars. Potatoes were mostly consumed by the second half of the 19th century (as a separate dish or added to main dish), replacing the turnips. Among other vegetables — pumpkin, cucumber, carrot, radish, cabbage, onion but in small quantities, often as fillings and condiments, not as basic food. Cucumber began to appear on the tables of the Tatars only in the early 20th century, and the Tatars were not familiar with our favorite tomatoes even in the mid-century.

The products were also canned. The Tatars salted melons, watermelons, cabbage was pickled. However, all this was borrowed from the neighboring peoples (Finno-Ugric, Russian), living nearby, and the vegetables for the future were prepared in small quantities, not in every house, and it was probably typical of the late 19th — early 20th centuries.

Meals of the rich and food for the commoners

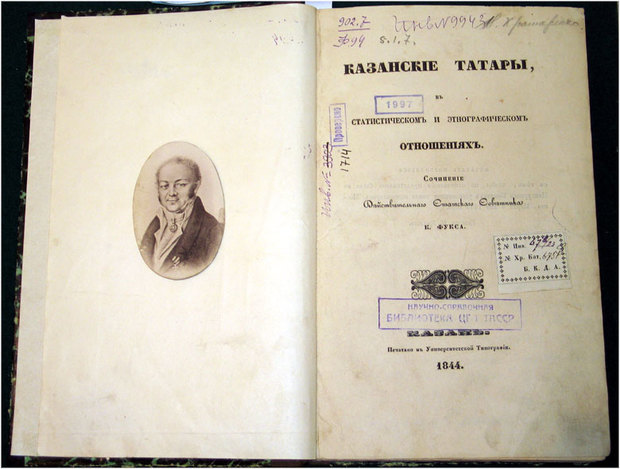

However, it should be taken into account that food of a wealthy Tatar and of a poor one could be radically different by the variety and amount of food on the table. Such nuances were described in the middle of the 19 century by K. F. Fuks: ''Usual food of the rich Kazan Tatars was following. Early in the morning, they drink tea and eat little cakes of rich dough with beef, called peremyadzh. At noon it is served a lunch: 1) pelmeni with beef and sour milk (kazan-bikmyasy); or pilaf, from Sarachinky wheat with raisins; 2) a round cake, called balysh, with meat and Sarakinsky millet; served with pickles; 3) roast goose or duck with potatoes; 4) boiled beef with radish or raw sauerkraut; 5) dried apricots, first drenched with hot water then cooled (ryk); 6) tea and small sweet cakes of the size of a hazelnut, called baursak. At 6 p.m. they again drink tea with cream and butter pies like in the morning. The dinner consists of pelmeni and noodles.

The food of the middle class and the poor Tatars was the following. In the morning they drink tea with kalachi; for dinner they eat noodles with beef or pelmeni. Food of the Tatar peasants: in the morning, rye flour, boiled in water with salt (balamyk or talkan); for lunch — salma, consisting of crumbling dough with mutton fat; and in the summer sour milk or kaimak of buckwheat flour in oil, in the evening again a boltushka of rye flour. On holidays – lamb. On the festival called Dzhin and in the wedding feast they eat horse meat.''

New times, new tastes

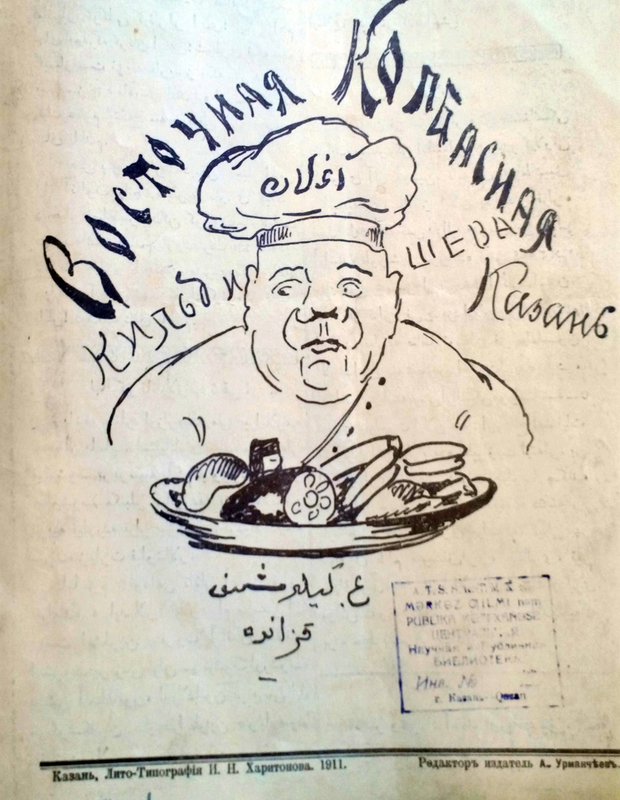

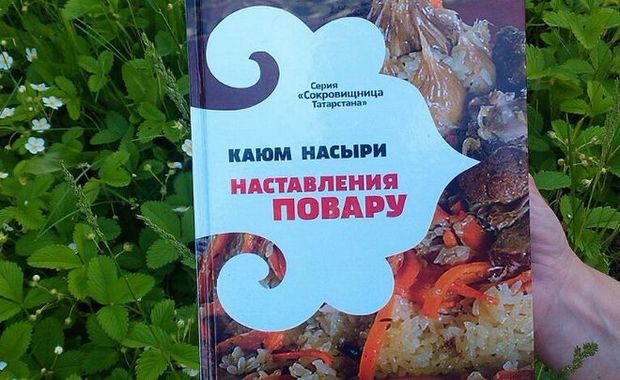

The turn of the 19th—20th centuries brought many changes not only in socio-economic terms for the Tatars but also the food system underwent significant transformation that particularly affected the urban population. A new food culture appeared along with products not typical for the traditional Tatar food (coffee, sausages, new and previously unfamiliar fruits and vegetables, European and factory-made sweets, etc.). In the rural areas, culture of farming was developed more, together with horticulture. Interestingly, at this time the first books on Tatar cookery were published. The pioneer was was Kayum Nasyri who wrote Instructions for a cook, and publishing house Gasyr published by A Master of cooking.

The 20th century brought various technological innovations. The appearance of plates has led to the emergence of new dishes, especially fried. The need for traditional furnaces and high boilers was gone that became the basis for changes in food preparation. In the cities, the food became more standardized, simplified, semimanufactures became more used. However, like in our days, the villages remained a stronghold for the preservation of traditions. At the end of the 1950s, a handbook of Tatar women for cooking by Yu. Akhmetzyanova Tatar cuisine in Russian and Tatar, which later was reprinted many times. The author of this publication worked together with anthropologists, travelled to villages, collecting the material.

Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, we have no such problems, which had been in the early 20th century, as for example described in the newspaper Bayanel-khak from 1909, in a note that ''Tatar young men despise Tatar girls… for their inability to cook European dishes''. In 2015, it was published the reprinted book by Kayum Nasyri Instructions to a cook that indicated the need of the society in the traditional recipes. In our days, despite the fast pace of life, it becomes important to preserve the culture, which consists of many parts, such as traditions and customs, and also such element of everyday life as food.