Bianca Pitzorno: ‘A person is by no means only what they read’

The Italian writer spoke about how reading became the building blocks of her autobiography, how attitudes toward Nastasya Filippovna have changed, and the peculiarities of childhood in Sardinia

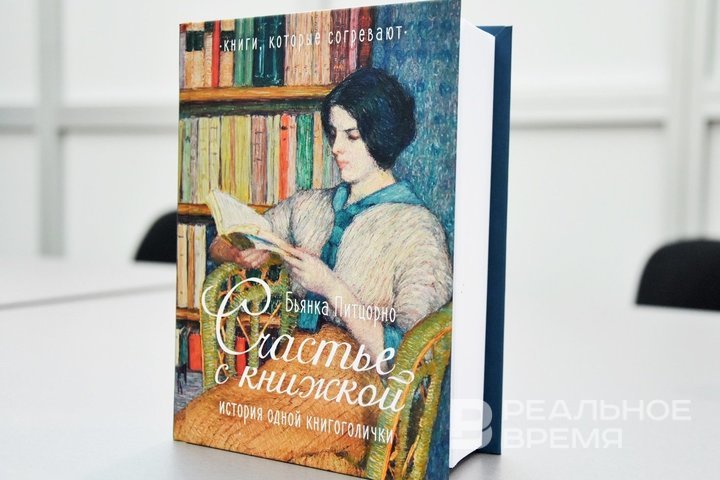

At the non/fictioNvesna fair, the discussion centred on the book Happiness with a Book. This is autobiographical prose by Italy’s most renowned children's author — Bianca Pitzorno. But it all began not with books. And not in Italy. It began on an island where the writer’s native language was not spoken.

Not quite Italy

Sardinia is easy to find on the map if you look just south of Corsica. Geographically — it is Italy, but linguistically — a completely different world. People there speak Sardinian, or Sardo, a language that even native Italian speakers cannot understand. It is not a dialect. It is a separate language. Bianca Pitzorno was born in 1942, in the midst of the war, right there — in Sardinia. It was Italy, but as if in parentheses. This is how the book’s translator from Italian, Andrey Manukhin, described it at the presentation: “She was born in Sardinia, on an island that for a long time was culturally cut off from Italy itself. In Bianca’s childhood, for example, there were no new books. Only those that could be found — passed down from parents or older relatives.”

Journalist, writer, and editor Mikhail Vizel added: “Bianca Pitzorno grew up in the 1940s and early 1950s. At that time, there was indeed a serious shortage of new book shipments to Sardinia. So the future writer grew up with interwar books from the 1920s and 1930s.” In Happiness with a Book, Pitzorno recalls growing up among the remnants of libraries where nothing new ever arrived. It was a country that had just renounced the monarchy. The girl was growing up in a new republic, reading books from the old world. “In 1946, Italy became a republic instead of a monarchy. This can be compared to a girl in the USSR in the 1920s growing up on books published in 1910," Vizel explained.

Madam Pitzorno could not and did not wish to write in Sardinian. And there was nothing to write, really: fiction in Sardinian simply did not exist. “That’s how it turned out historically. The earliest written records in the Sardinian language are monastery inventory lists and the legal code of the island’s ruler, Eleanor of Arborea,” said Bianca Pitzorno, who joined the presentation online.

There was a language, but no literature. There were only songs. “It is a distinct language, not a dialect. In Sardinia, there are songs, poetry. The earliest examples of poetry date back to the 17th–18th centuries, and they have been preserved in written form. And there is a large oral song tradition,” the writer explained. Bianca had a friend, the famous singer Maria Carta, who sang only in Sardinian. “It is very beautiful poetry — oral, either folk or authored — but created for performance in the form of songs,” Madam Pitzorno added.

The Sardinians themselves did not consider Bianca one of their own: “I come from a bourgeois family of Italian origin, from the mainland, as the Sardinians say. They divide themselves into Sardinians and continental citizens — that’s how Sardinians refer to other Italians. And even a non-Sardinian will still divide people this way, simply because they were born on the island.”

The Pitzorno family spoke only Italian. It was her only written language — and her primary, native tongue. “No one in my family spoke Sardinian, everyone always spoke Italian. All my books I write and have written in Italian. For me, it is my main and native language,” the writer said at the meeting. She did not read or write in Sardinian. But in Italian, French, German, and Spanish — yes. Pitzorno made a point of reading literature in the original in those languages. “I live more in Milan than in Sardinia. I left Sardinia at the age of 30. And for the past 50 years, I consider myself a Milanese rather than a Sardinian,” she admitted.

“Bianca Pitzorno wanted to become a teacher, to teach ancient languages in a lyceum. But midway through her university studies, she became interested in anthropology and archaeology, transferred to another faculty, and defended a very challenging thesis,” Manukhin explained. It is precisely this chapter of her life that Pitzorno describes in detail in Happiness with a Book.

Then came Milan. Television. Screenwriting. “Madam Pitzorno moved to Milan, enrolled in film school, and then, for about 15 years, wrote scripts for children’s television programmes,” the translator continued. And only after that — books. More than seventy. For children. And in recent years — for adults as well. “That was an unexpected turn for Italy,” Manukhin said of Bianca Pitzorno’s shift to writing for adults.

From Nastasya Filippovna to gardening

In Happiness with a Book, Pitzorno writes not simply about books. She turns reading into the architecture of a biography. Everything begins with childhood, where pages take the place of streets. But, as the writer herself admitted, behind this structure lies a principle — life experience always comes first, and books merely complement it. “A person’s life is built primarily from the experiences they receive and go through. Books have undoubtedly become a significant, formative part of that experience,” she said at the presentation.

Happiness with a Book is not the only attempt to piece together her life. There was also an autobiography told through animals. Next came the idea for a book about plants. Gardening, horticulture, and communication with flora. Pitzorno is seriously considering the idea of writing memoirs based on... shoes. “If I were offered to write memoirs relying on the shoes I have worn throughout my life, it would, in principle, be feasible. And it might also be a very interesting interpretation of my life, my biography,” the writer said.

But it is books — the first filter. Unique and flexible. Not merely a list of what has been read, but a way to reinterpret what has been lived. Once at 14, then at 40, later at 80. This is what happened with Anna Karenina. Mikhail Vizel reminded the audience that in Pitzorno’s book she describes how her attitude towards Tolstoy’s heroine changed with age. At twenty — one emotion, at forty — another, at seventy — a third, and now, past eighty — a completely different one. He asked which other characters from Russian literature have undergone such an evolution of perception?

Pitzorno’s answer was precise and painfully personal: “I can speak of two books, two masterpieces of Russian literature, that have accompanied me throughout my life. And the characters in these books, their perception and evaluation, change as I gain new life experience, as my views evolve, as the general situation — including that of the country — shifts, and as my overall perspectives on certain matters transform.”

The first book — The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoevsky. At first, Nastasya Filippovna seemed distant. In youth, much slipped by — quite literally. Only later did it become clear that the fact she was forced into something akin to prostitution was entirely missed on the first reading. “The next time I returned to this book, I approached the character of Nastasya Filippovna differently and with greater understanding. I felt more sympathy for her than for Aglaya, whom I had previously favoured,” Bianca Pitzorno recounted.

The second — The Kreutzer Sonata by Leo Tolstoy. Pitzorno first read it at 14, and at that moment everything seemed perfectly clear: the “bad wife” had been unfaithful to her husband. “But with subsequent readings, and there were many, the picture became more ambiguous, more complex, more multifaceted…” the writer added. Especially after the rise of feminism in Italy. Newspaper reports, jealous murders, real-life dramas — all of these intertwined with her perception of Tolstoy’s character. What once seemed a moral manifesto transformed into a story of violence.

Vizel reminded the audience of the context. Until 1977, legal divorce did not exist in Italy. Issues that today are seen as ideological — women’s rights, legal freedom — were simply unavailable then. Thus, a feminist perspective became essential for Pitzorno, including when returning to Tolstoy.

But Happiness with a Book is not limited to Russian literature alone. As the Italian studies expert Anna Yampolskaya clarified, Pitzorno opens up an entire panorama — from classics to current trends, from school curricula to Hungarian novels that became an unexpected phenomenon. “We are dealing with a reader who is voracious for books, a reader who adores literature and experiences it deeply,” Yampolskaya noted. The book contains evidence of literary fashions — first a boom in Hungarian authors, then a surge of interest in Latin America, followed by Russian classics. “In this book, we can find a wealth of information about what could generally be read in Italy,” the Italianist emphasised.

Most importantly, the book seems to invite dialogue. “For me, this book is valuable because it can encourage each of us to write our own reading biography or, at the very least, to see our own lives and reflect on the formation of our personality from this perspective,” added Anna Yampolskaya. Not “what I have done,” but “what I have read.” And how that has influenced me.

According to Pitzorno, not all readings are the same. Reading varies. Some people perceive books as a collection of plots. Others see them as reference points in their own lives. And for some, literature never becomes the building blocks that shape personality. This is neither good nor bad — it is a fact. “A person is by no means only what they read, because the very process of reading is different for different people. Yes, there are indeed people who read books that change them, and this becomes part of their biography. But there are also intelligent people who read much less, yet act in this world. And their lives become interesting subjects for writing books about them. I have known women who read little or were even illiterate, but they told their life stories, events, and fascinating facts in such a way that you want to write a book about all of it,” said Ms Pitzorno.

Happiness with a Book is a work that cannot be read superficially. The book demands pauses, recollections, and perhaps reconsiderations. It is important not only what the text itself says, but also how it resonates with the reader’s past.

Ekaterina Petrova is a literary critic for Realnoe Vremya online newspaper and the author of the Telegram channel Bulochki s Makom (Buns with Poppy Seeds).