Iranian cinema: Iranian heritage and sentimental self-censorship in the country of Ayatollahs

Review of Iranian films and the phenomenon of Persian art

Kazan director and columnist of Realnoe Vremya Renat Khabibullin who, by the way, will participate in the upcoming Festival of Muslim Cinema talks about the phenomenon of Iranian cinematography. In today's op-ed column written for our online newspaper, he shows the evolution of Persian film art, finds salient features of Iranian masters' films and considers uneasy relations of directors with the regime in the Islamic republic.

Development of Persian cinema: from Odessa and Rostov towards Italian neo-realism

Nowadays the cinematography of the Islamic Republic of Iran is probably the most curious area of research for film experts and critics. Not only the ethnic component but rather those principles and foundations that dominate in Iranian cinema are curious.

Cinematography appeared in Iran in the early 20 th century like everywhere. As a rule, the first cinemas showed works brought from Odessa and Rostov-on-Don. In the future, communist ideas of Soviet Russia became one of the reasons why western cinematography drove the Soviet one out from Tehran's screens. Iran, Persia back then, started to make films a bit later than Russia. Ovanes Oganyan shot the first live-action film called Abi and Rabi in 1931. Students of the first film school of the capital that very Oganyan opened performed roles there.

As strange as it might be, Iranian cinematography did not play any significant role in world cinema then. Persia's rich cultural heritage became a basis for the creation of objects of art with the language of cinematography in this country many times but did not have any big wins in this field.

Development of Iran's cinematography began in the 60s. There were shot over 60 full-length films in the country in the late 60s. State support provided not only with necessary production capacities but also organised festivals. And a film department was founded in the Ministry of Culture, censorship was created, new film schools opened.

Westernisation and de-Islamisation policy that developed on a large scale during those years were seen in the cinematography. In this respect, religious circles saw only ''a Plague from the West'', which was featured in theologian Jalal Al-e-Ahmad's namesake work. The Western rhetorics did not find support among the people.

Dariush Mehrjui's The Cow that received recognition in both Iran and outside it like amazed opinions of film critics and success in the market and film festivals was the most important work of that time. Italian neorealism with its title topic of addressing ordinary people's everyday life influenced Iranian cinematography the most.

The Islamic revolution was the most important era for Iran's cinematography. The shah's overthrow and the establishment of a Sharia society, as Shia revolutionists headed by Ayatollah Khomeini understood it, defined the development vector of Iranian cinema for tens of years. The religious leader of Iran himself defined the main social doctrine of the most important art of the new Islamic Republic of Iran. An ordinary person's life was to be the main topic. And in this sense, the succession of ideas of Italian neorealism is seen better.

You will recognise it anywhere

The following features of Iranian cinema can be pointed out:

- Absence of violence and blood.

Violence as the main moving element of the cinema of all the times was taken away from the context of the Iranian idea of cinematography. However, the topic of war has never left Iran's territory and had rather metaphysical and philosophic components. Blood was almost completely washed away from screens, which became an important leak in the aesthetic perception of Iran's spectators who even did not start considering cinema as beautiful bloodbath. - Unprofessional actors in live-action films.

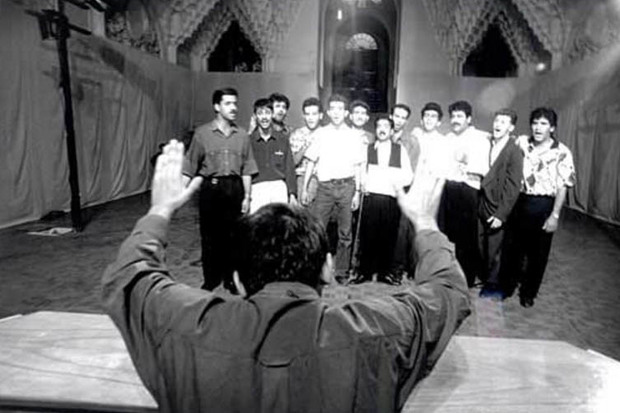

This component became the gimmick of the Iranians, so to speak. Iran's directors were those who were not afraid of hiring unprofessional actors. Young Konchalovsky's experiments in The Story of Asya Klyachina were successful. Iran walked and continues walking in this space freely challenging themselves again and again, for instance, like in Hello Cinema where director Mohsen Makhmalbaf announced casting where a huge crowd gathered. Each of the invited people was dreaming of being shot in the film. How surprised they were when they knew they already were in the film and their dream came true because the film would consist of film tests. Makhmalbaf's truly amazing experiment opened the next typical feature of Iranian cinema. - Blurred lines between documentary and live-action film.

Yes, use of unprofessional actors often makes spectators forget the aesthetics of playing perception, and authors of Iranian cinema skillfully keep a balance on the border of two genres that can seem incompatible. Life in the focus of an Iranian cinematographer is so realistic that the confluence of a documentary with a live-action film creates a new perception angle because a person himself surreptitiously becomes a participant of the events he sees on the screen at the cellular level.

Another important feature of Iranian cinema was that here people are not afraid of making spectators feel sincere sympathy for heroes. The topic of childhood is major among many classics of Iranian cinema. Photo: instagram.com/muhammadmovie - Sentimentality.

Another important feature of Iranian cinema was that here people are not afraid of making spectators feel sincere sympathy for heroes. The topic of childhood, which is major among many classics of Iranian cinema, particularly Majid Majidi, is an important component. Right his film Muhammad was the winner in Discovery Film of the 2016 Festival of Muslim Cinema in Kazan. In this work, Majidi showed the Islamic Prophet's life precisely in his childhood. Unfortunately, from an emotional perspective, the film was not as good as the author's classic works. Probably serious censorship the director faces caused it. Nevertheless, the Iranians are not afraid of tears until today, which makes them different from the Western idea of cinema where the task is to encourage spectators' passions, not their education and purification. - Absence of bedroom scenes.

Iranian cinema has always paid attention to the topic of the relationship of genders. However, the delicacy the authors talk about this topic causes a lot of interest. Without doubt, there are also artists who are ready to cross generally accepted norms for visual expression. But the censorship is on guard – the term that is almost abusive in Western understanding while necessary and quite strict in Iran. According to some data, there is not a code of rules and commandments about how Iranian cinema should look in the eye of censors. Internal understanding of the idea of things was already sealed in the Iranians' consciousness at the cellular level, though very authors can disagree with censors' opinion. For instance, in Majidi's Muhammad, the face of the future Prophet is not shown while in the Majid Majidi's interview to Realnoe Vremya, the director frankly gave to understand that he did not think it was a strictly forbidden to show the face of Allah's messenger. There are breaks here as well. Director Mani Haghighi, for instance, told how he had to justify himself because in a film frame a donkey with a green horsecloth falls and breaks a leg. Censors ran parallel of the green horsecloth to Islam because the green colour is traditionally considered the colour of this religion. It turned out Islam, in Haghighi's opinion, is a limping donkey. Of course, the director did not think anything like this but had to give a serious answer. When Haghighi was told a story about Attention, Turtle! (1969) where kids decided to check whether the turtle's shell would hold the weight of a real tank while USSR censors noticed the analogy of the turtle with Czechoslovakia where Soviet tanks entered. The Iranian director said the censors were right there. So censorship is present everywhere in Iranian cinema as its constant and indispensable part.

In the context of their understanding of cinematography, the Iranians are free of instructive intonations in films. Encouraging an intellectual, careful acquaintance with the films, authors of Iranian cinema try to talk to spectators in a language that has been almost forgotten in the Western society. Probably this is why right Iranian films have won Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film twice in the last 5 years. Asghar Farhadi won the statuettes twice for A Separation and The Salesman. I will agree that the latest victory of the author mainly became a political walkout in protest of the film community of the USA against newly-elected President Trump who banned the entry to the country for citizens of several countries including Iran. Very Farhadi was not at the ceremony because he could not enter the democratic country. However, the tendency that defined a growing influence of Iranian cinema became obvious to everyone.

Directors and politics

The greatest directors representing the Islamic Republic of Iran have both different political views and understanding of cinema as it is. Abbas Kiarostami who passed away in 2016 is the most famous of them. This director was an intellectual and philosopher. Classic films Taste of Cherry and Where is the Friend's Home are his works. Kiarostami saw the value of life as it is as major topic of his art, which was reflected in many of his films. And not always his approach correlated with religious canons. He was likely to even stay apart from ready answers he, undoubtedly, was acquainted with from Quran considering his own internal experience important as well.

During the last years, Kiarostami worked outside Iran. Acting without patterns, as usual, he found a unique language to communicate with spectators that was common only to him like in Certified Copy with starring Juliette Binoche.

Before the Islamic revolution, above-mentioned Mohsen Makhmalbaf was in prison for attacking a government official. He spent five years in prison. When the revolution won, he was among active supporters and propagandists of the new regime for some time. However, he did not remain in this group for long but he had an opportunity to shoot films. Views of this director or, more precisely, their transformation, were shown in Boycott that tells about a revolutionist who is waiting for his sentence and has unlimited authority and respect among his supporters but understands in his soul that his ideas he is punished for were false. Amazing experimentalist, innovator and just brave person Mohsen Makhmalbaf deserved a detailed study as the brightest representative of Iranian mentality in cinema. The above-mentioned influence of Italian neo-realism is demonstrated not only in the aesthetics of Makhmalbaf's films but also in names. Great work The Cyclist about an Afghan man who decides to participate in a race to earn money for his wife's medicine seems to pay tribute to genius Vittorio de Sica with his Bicycle Thieves.

Director and documentary maker Jafar Panahi draws a lot of attention. The West considers Panahi as victim of the Iranian political system that punished him for participation in street protests in 2010 with forbidding to make films until 2030. Nevertheless, the director finds all possible ways to do what he loves. In 2011, his film participated in the film festival in Cannes. The very director continues looking for new forms during very strict pressure. And the ways Panahi shoots new works are no less interesting than his films themselves.

And, finally, Majid Majidi. Right his recent work today made me study Iranian cinema as phenomenon. Very Majidi has neither opposed the power nor sung its praises. As a life classic of Iranian cinematography, he became popular in the 90s for Children of Heaven and The Color of Paradise. The topic of childhood became major in Majidi's art from the beginning until today. It gave the director many opportunities, freed from additional questions from censors and allowed to add circumlocution in stories that seem a child's game at first sight. Unfortunately, Muhammad that finally reached Tatarstan cinemas did not become very successful among spectators. Nevertheless, the appearance of a film of such a scale is a brave call saying that Iranian cinematography will be able to open new horizons and is not afraid of big forms. Without doubt, this brief review is not able to cover even the tenth part of what cinema of Iran actually is. One can really understand what this Iranian phenomenon actually is only by acquainting with works of authors from this wonderful country.