Zilant and barses: the path from a basilisk and ‘a lamb with a gonfalone’ to a crowned dragon

The heraldry specialist about the five centuries of evolution of the Tatarstan symbols

The erected around the Kazan family centre Chasha ('Bowl') statues of 'the guardians' in the form of dragons and winged barses provoked a lot of controversies among the citizens. However, the sculptor Dashi Namdakov chose these animals for the reasons. These mythical creatures have been symbols of Kazan since ancient times. About the history of the main symbol of the capital of Tatarstan — Zilant — in the column written specially for Realnoe Vremya by a member of the Heraldic Council under RT President Grigory Bushkanets.

'A predatory animal with a raised front paw'

The first historical monuments linking the image of a black winged snake with the names of Kazan, Kazan Tsardom go back to the Russian period of history of the city, but it takes its origin in the earlier historical period — the period of the Kazan Khanate.

The earliest image among the known ones, which subsequently became the coat of arms of Kazan, is, apparently, 'the flag of caesar of Tataria, yellow, with a black lying and looking outside dragon (great serpent) and with a basilisk tail'. This drawing and description are given in the book of Karlus Alyard, the book with the long title on the ship's structure and flags, which was published in Amsterdam in 1705, and in 1709 at the order of Peter I translated into Russian language and published in Russia.

The earliest image among the known ones, which subsequently became the coat of arms of Kazan, is, apparently, 'the flag of caesar of Tataria, yellow, with a black lying and looking outside dragon (great serpent) and with a basilisk tail'. This drawing and description are given in the book of Karlus Alyard, the book with the long title on the ship's structure and flags, which was published in Amsterdam in 1705, and in 1709 at the order of Peter I translated into Russian language and published in Russia.

The following drawings are found on the early-heraldic monuments of the end of the XVI — XVII centuries alongside the images of the heraldic symbols of the Bulgarian Empire.

In particular, on the seal of Ivan the Terrible in 1577 in the center there is a double-headed Russian eagle, around it — the seals of the thirteen lands, including the seal of the Tsardom of Kazan: 'The dragon in a crown, the body, two front paws of an animal, a ring snake tail,' and the Bulgarian seal: 'A wild animal with a raised front paw.'

The embroidered with silver and studded with pearls veil of the backrest of the throne of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich of the second quarter of XVII century also depicts a double-headed eagle with the Moscow coat of arms, and the edges are embroidered with the twelve seals of the tsardoms and oblasts, including 'The lying dragon in a crown with raised front paws, ring tails' (the inscription — 'The Seal of Kazan') and 'Walking animal with a raised front left paw' (the inscription — 'The Seal of Bolgoria').

The embroidered with silver and studded with pearls veil of the backrest of the throne of Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich of the second quarter of XVII century also depicts a double-headed eagle with the Moscow coat of arms, and the edges are embroidered with the twelve seals of the tsardoms and oblasts, including 'The lying dragon in a crown with raised front paws, ring tails' (the inscription — 'The Seal of Kazan') and 'Walking animal with a raised front left paw' (the inscription — 'The Seal of Bolgoria').

The armorial banner of the Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich (1666-1678) also includes the Bolgarian and Kazan emblems: 'the Seal of Kazan, the basilisk in the crown is on it, wings of gold, the end of the tail of gold', 'Seal Bolgarian, walking bars on it'.

Finally, in 1672, the first written source appears — the Big State book, containing the descriptions and drawings of the coats of arms of tsardoms and oblasts that were a part of the official title of the Russian sovereign, and therefore it is called 'Titulyarnik'. It provides the following descriptions of Kazan and Bulgarian coats of arms: 'Lying dragon in the crown, to the left. The inscription: 'Tsr of Kazan'; 'Walking predatory animal with a gonfalon, to the left. The Inscription 'Bulgarski'.

Finally, in 1672, the first written source appears — the Big State book, containing the descriptions and drawings of the coats of arms of tsardoms and oblasts that were a part of the official title of the Russian sovereign, and therefore it is called 'Titulyarnik'. It provides the following descriptions of Kazan and Bulgarian coats of arms: 'Lying dragon in the crown, to the left. The inscription: 'Tsr of Kazan'; 'Walking predatory animal with a gonfalon, to the left. The Inscription 'Bulgarski'.

About how the bars was nearly turned into a Christian symbol of 'a lamb with a ganfalon'

The last historical artefact of the XVII century, where we find a picture of the still not officially approved symbol of Kazan and the Bulgarian coat of arms, is the image of the Russian state seal from the diary of Korba, who accompanied in 1698-1699 the ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire, sent to the Russian court for negotiations on the war with Turkey: 'Standing on the bird's legs with spread wings dragon in the crown, to the left'. And the inscription in Latin 'Casan'; 'Walking lamb with a gonfalon, to the left'. And the inscription in Latin: 'Bologaria'.

The last historical artefact of the XVII century, where we find a picture of the still not officially approved symbol of Kazan and the Bulgarian coat of arms, is the image of the Russian state seal from the diary of Korba, who accompanied in 1698-1699 the ambassador of the Holy Roman Empire, sent to the Russian court for negotiations on the war with Turkey: 'Standing on the bird's legs with spread wings dragon in the crown, to the left'. And the inscription in Latin 'Casan'; 'Walking lamb with a gonfalon, to the left'. And the inscription in Latin: 'Bologaria'.

Zilant on the regimental colours

The beginning of the eighteenth century was marked in Russia's with the military reform carried out by Peter I. As a result, the military regiments were stationed in the cities and almost all got their names from the place of deployment. Along with the names, the regiments received the emblems of the cities placed on the colours. So, on the colours of the Kazan regiment in 1712 there appeared the emblem already known from the Titulyarnik.

The beginning of 1721 is marked in the heraldic history of Russia by the establishment of the post of the King of Arms, which was the result of active participation of the state in the streamlining of the rights and responsibilities of service class of Russia. The main duty of a King of Arms was supposed to be oversight of the military and civil service of the nobility. The heraldry work, according to the plan of Peter I, was to be a minor part of the work of a King of Arms.

Very quickly the large number and diversity of the duties of the King of Arms resulted in the formation of the whole staff, i.e. the establishment of the Office of King of Arms' Affairs. On 12 April of 1722, at the personal decree of Peter I Francisco de Santi was appointed as the King of Arms. In the five years of his service in this position, Santi did much to create coats of arms of the Russian cities. However, in June of 1727 he was accused in conspiracy and exiled to Siberia. His work on the Russian city coats of arms is unfinished.

'Black snake, under a gold crown'

However, in the affairs of the King of Arms Office in various years there are documents that can be the basis for the reconstruction of Santi's work on the creation of coats of arms. These documents include primarily the inventory of drawings and papers, made in the apartment of Santi after his arrest. Among other things in this inventory there are 98 drawings of coats of arms, meant to be placed on the colours of the regiments, which Santi did at the order of the War Collegium since February of 1727. Among them — the picture of the colours of the Kazan regiment that remained unclaimed by force of circumstances.

However, in the affairs of the King of Arms Office in various years there are documents that can be the basis for the reconstruction of Santi's work on the creation of coats of arms. These documents include primarily the inventory of drawings and papers, made in the apartment of Santi after his arrest. Among other things in this inventory there are 98 drawings of coats of arms, meant to be placed on the colours of the regiments, which Santi did at the order of the War Collegium since February of 1727. Among them — the picture of the colours of the Kazan regiment that remained unclaimed by force of circumstances.

In 1729, by the order of the War Collegium, under the leadership of General Christoph von Münnich it was composed the book of armory, which included drawings of 88 regimental colours. The book of armory was submitted from the War Collegium to the Supreme Privy Council. In the early 1730, the War Collegium ordered to make the regimental colours with the coats of arms from that book. There is the description of the coat of arms image for the colours of the Kazan regiments from the book of Münnich in the famous book by Alexander Lakier 'The Russian Heraldry': 'A black snake, under a gold crown, Kazan, red wings, white field'.

The approved coats of arms of Kazan

All above mentioned images of the Kazan Zilant although was directly associated with the city, but, in the first place, had purely practical value, because it was created to be placed on certain seals or regimental colours.

Kazan gets its Highest approved city coat of arms together with other cities of the Kazan Governorate on 18 October of 1781 by the decree of Catherine II: 'Black snake, under a gold crown, Kazan, red wings, white field (Old coat of arms)'. 'Old coat of arms' means the coat of arms was not specially designed in the XVIII century for its approval, like most of the coats of arms of the cities, including Kazan Governorate, and it has ancient historical roots and was known long before its official approval…

Kazan gets its Highest approved city coat of arms together with other cities of the Kazan Governorate on 18 October of 1781 by the decree of Catherine II: 'Black snake, under a gold crown, Kazan, red wings, white field (Old coat of arms)'. 'Old coat of arms' means the coat of arms was not specially designed in the XVIII century for its approval, like most of the coats of arms of the cities, including Kazan Governorate, and it has ancient historical roots and was known long before its official approval…

By the mid-nineteenth century, all manufactured in the Heralds Office and then in the Department of Heraldry, diplomas, certificates and coat of arms were subjected to the approval of the Minister of Justice. However, not having sufficient competence in the heraldic art, the Minister put before the government the question of the establishment of the department of special branch. A special department for the creation of coats of arms, the so-called Arms Office, was established at the Department of Heraldry on 10 June of 1857. It was headed by the keeper of numismatic cabinet of the Hermitage, the baron Bernhard (Boris Vasilyevich) Kene.

One of the first works by B. Kene as the head of the Department of Heraldry was the framing of rules for decoration of the coat of arms of provinces, regions, cities and suburbs, which were highest approved already in July of 1857.

In accordance with these rules, on 23 January 1859 the coat of arms of the governorate city of Kazan received the approval of the Senate, and later, the coats of arms of district cities of the Kazan Governorate did, where Zilant occupied already not the top half of the shield, like in the coats of arms in 1781, but free part.

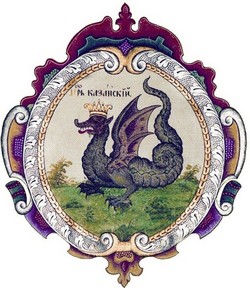

The coat of arms project of Kazan with decorations by Kene had the following description: 'In a silver field there is a black crowned dragon; the wings and tail are dark red, the beak and claws are golden, the tongue is dark red. The shield is crowned with Kazan crown and surrounded by two Golden spikes, connected by Aleksandrovskaya ribbon according to the Highest approved rules.'

Heraldry is back together with new Russia

Since 1917 and until the second half of the 1960s, the territorial heraldry was almost absent in the life of society. The coats of arms of the XVIII–XIX centuries although were not officially abolished but were forgotten and not used. Only in the second half of 1960s some interest in heraldry was reborn and they started to develop the city coats of arms with new, Soviet symbols. However, to these local symbols, drawn without regard to the rules of heraldry, it is impossible to fully apply the word 'coat of arms', and therefore it is appropriate to call them 'arms-like emblems".

A new stage in the modern heraldry of Russia began in 1992, when it was revived the State Heraldic Service (today — the Heraldic Council under the President of the Russian Federation). The Heraldry Service is designed to provide professional assistance in the creation of heraldic symbols, to monitor compliance with the rules and traditions of heraldry. To implement these tasks the official signs (coats of arms, flags, emblems, awards, uniforms, etc.) approved by the Russian authorities (of federal, regional and municipal levels) are examined in the Heraldic Council.

On the threshold of 1000-anniversary Kazan formalized its official symbols be legislation. On 24 December of 2004, by decision No. 37-21 of the Kazan Council of people's deputies it was approved the following heraldic description of the coat of arms of Kazan: 'In a silver field on green ground, the black dragon with dark red wings and tongue, with gold paws, claws and eyes, crowned with a Golden crown. The shield is crowned with the Kazan Сap'. The coat of arms is included in the State Heraldic Register under the number 1700.

On the threshold of 1000-anniversary Kazan formalized its official symbols be legislation. On 24 December of 2004, by decision No. 37-21 of the Kazan Council of people's deputies it was approved the following heraldic description of the coat of arms of Kazan: 'In a silver field on green ground, the black dragon with dark red wings and tongue, with gold paws, claws and eyes, crowned with a Golden crown. The shield is crowned with the Kazan Сap'. The coat of arms is included in the State Heraldic Register under the number 1700.

The snake king and the valiant warrior

Where did this 'black crowned dragon' appear from? which remains the constant symbol of Kazan already for five centuries? The history does not have reliable information that would explain it. All that is left to do is to believe the legend that tells about it: 'Once Kazan was not in the place where the city is now but far upstream of the Kazanka River. The girls who had to walk for water blamed the Kazan Khan because he placed the city high on a hill, and it was hard to climb with buckets of water.

The Khan was offended by that and ordered the girls to come to him. One of the girls said to the Khan: 'It is not you whom I blame, the wise Khan, but the place on which you put the city'. The Khan replied: 'If you know how to blame — then find a new place for the city!'. The girl again did not panic and offered to transfer the city to the apiary of her father, just at the place where now is located Kazan.

But everything was not so simple. In the place that the girl offered there were a lot of snakes. The Khan became sad. The girl wisely advised him: 'In winter, when all snakes hibernate, order to surround the entire hill with firewood, and when the snakes wake up and come out to bask in the spring sunshine, burn the firewood'.

So they did. All the snakes died in the fire. And only the snake king — the winged dragon Zilant — flew to the other side of the Kazanka River, the hill Jilan-Tau (the Zilantov Hill), where from terrified the citizens for a long time. However, as usual in the legends, each dragon has its baghatur (the valiant warrior). He was found in Kazan as well. Zilant was defeated. In memory of this event the citizens placed it on the city's coat of arms.'