Tourism as a new cotton: globalization à la Uzbek in Bukhara

Report from post-Karimov Uzbekistan. Part 1

The correspondent of Realnoe Vremya has returned from a trip to Uzbekistan with a series of travel notes about this Central Asian Republic going through a period of post-Karimov 'thaw'. We offer to your attention the first part of his report dedicated to Bukhara. We thank the State Committee of the Republic of Tatarstan for the organizational support of this material.

The closed city of Central Asia opens again

The combination of global trends and local peculiarities in the twenty-first century permeates most political events, conflicts and phenomena in the economy. But the city of Bukhara has been living in this mode for more than two and a half thousand years. On souvenirs one can see the image of a fairy town, where caravans travel across deserts. Indeed, Bukhara for many centuries was a prominent hub of transcontinental trade.

On the other hand, in the past Bukhara had a reputation as the closest city in Central Asia. Ármin Vámbéry, a Hungarian scientist and adventurer, who in 1863 was the first European who got there, had to get into the character of a wandering dervish and take risks every day. This Bukhara secrecy had its own truth. The liquidation of the Emirate of Bukhara, after which Bukhara entirely 'opened to the world', was accompanied by a destructive fire of the old town. The damage caused by the artillery of Mikhail Frunze in 1920 has not been replenished to this day. But the miraculously survived historical center remembers former way of life, when people lived in closed quarterly communities – mahallahs, and over the crush of narrow streets there dominated the citadel Ark.

Today's Uzbekistan rediscovers itself to the world. Given what challenges the famous Central Asian demography and geography of the country bear, the authorities do everything to make this process manageable. Attracting foreign tourists and increasing participation of its citizens in the tourism industry – one of the methods of globalization à la Uzbek. And, of course, it is impossible to do without Bukhara in this matter.

The city of old stones without high-rise buildings

The main value of Bukhara is the old city, which can be explored on foot in a few hours not leaving the historical architectural environment. It is how Bukhara differs from Samarkand, where the magnificent buildings of the past are like islets in the modernity. It doesn't really matter that Bukhara masons sometimes patch the voids formed in the historic building, but in general Bukhara is a city of old stones. The neighborhoods that stretch across the sides of the tourist streets are residential, and the locals walking with their children, sitting in teahouses and on the benches are live, real.

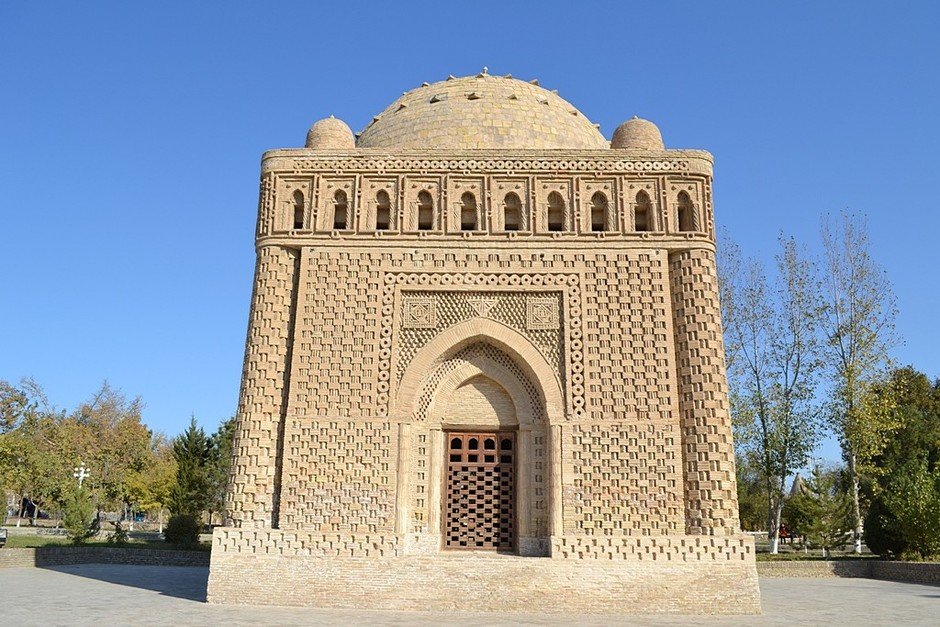

Everywhere there are blue mosaic facades of mosques and madrassas. Only a specialist can 'read' them and tell the difference between them. For most tourists it is just a standard hallmark of the region, it needs no explanation. But in Bukhara they know how to present this kind of attractions. For example, the square Lyab-i Hauz is situated around an artificial pond, Hauz, lined with trees. There is an easy and relaxed atmosphere that highlights the monument to Nasreddin Hodja. The portal of the local madrasa, decorated in the seventeenth century with bird-simurghs, also looks easily and naturally. After going through narrow shopping streets, we go to the architectural complex Po-i-Kalyan. Here, the ease is inappropriate. The 46-metre minaret and the biggest in the city mosque are designed to inspire awe. On the opposite, it is located Miri-Arab madrasah – the temple of the Islamic Sciences.

''Only in Bukhara the light comes from under the ground''

For a long time it was the most important Muslim educational institution in out country. Every Muslim region of the former USSR has its graduates of Miri Arab, and they are the elite of the Islamic ummah. Their names are well known not only to the believers. Galimdzhan Barudi for the Tatars is more than just a mufti, he is one of the fathers of the nation. Akhmad Kadyrov is more than just a mufti for the Chechens. In Bukhara they like to recall how Ramzan Kadyrov came to the alma mater of his father.

The name 'Bukhara' originates from Sanskrit vihara – a Buddhist monastery. At the dawn of the city formation, Buddhism was influential religion in Central Asia. Besides Buddhists, in Bukhara and the surrounding areas there lived and preached the Zoroastrians, Christians, Manichaeans. But Bukhara took the exceptional place in the Islamic civilization. Muhammad al-Bukhari, the author of the most authoritative for the Sunnis collection of hadith, and Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari, the founder of the popular all over the world Sufi Muslim orders, the Naqshbandi, are natives of Bukhara.

For a billion Muslims, Bukhara is not only the regional centre of Uzbekistan but the shrine city. The guides in Bukhara tell the old Eastern proverb, ''Throughout the world the light comes from heaven and only in Bukhara it comes from under the ground.'' The proverb alludes to the thousands of Islamic saints buried in these places.

In the first decades of independence, Uzbekistan several times teetered on the brink of a civil war in choosing secular or religious path. It was chosen a secular path, according to which the country continues to live until today. But the reversal of modern Uzbekistan to the world means not only intensification of contacts with Europe and America. They are also expanding cooperation with Islamic States. One of the forms of rapprochement – ziyarat tourism, i.e. organization of pilgrimages to Islamic shrines. Around the mausoleum of Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari and the seven feasts of the Sufi buried in Bukhara region, it is growing a special tourism industry. Malaysia and Indonesia are the first in line of pilgrims from Southeast Asia to visit Bukhara's shrines. Russia, with its considerable Muslim community, is not visible yet.

Entertainment for foreigners and pure poetry for pensioners from kishlaks

It is natural for Uzbekistan as a country with a statist political culture that building the tourism industry is centralized at the state level. In four regions with high tourism potential there have been appointed deputy khokims (i.e. governors) for tourism development. These regions, in principle, are on everyone's lips. It is Xorazm Region with of ancient Khiva, Bukhara Region, Samarkand Region and Tashkent. Tourism deputies have the powers to influence the work of all organizations that are associated with tourism, including banks on the issues of project financing and law enforcement agencies to curb the operation of illegal tour guides.

Deputy khokim for tourism development in Bukhara Region, Botirzhon Shakhrierov, is local, but he built his career in Tashkent. On his current position he has already launched several initiatives. The first is to create entertainment zones for tourists. The historic centre is a quiet and sacred place, where after nine o'clock the life come to a standstill. There will be a designated area outside the center for tourists where they can watch a movie in a mini cinema, go to a disco, swimming pool. The entertainment area is to be available from 2019.

The second initiative is aimed at maintaining the nascent tourist industry during off season. At the same time, the government is tackling the issues of cultural education of the rural population. According to a domestic tourism program, every district from November 20 until the end of March daily send 500 people on a tour of the attractions of the area. The first day is devoted to the sightseeing of the Holy places of Islam outside of Bukhara. The tourists spend the night in a hotel in Bukhara, and the next day is dedicated the city's attractions. The cost of such tour is 100,000 soʻms ($12). This money will allow the hotels, guides and other members of the tourism industry to survive the most critical months of the year, and the villagers will have an opportunity to escape from their kishlaks and see the big world. For many older people who lived all their life in rural houses, to be in a modern hotel room is the ultimate luxury they have ever seen.

The program of domestic tourism is implemented with Uzbek scale. The Union of Youth of Uzbekistan is responsible for organization of school students. The working population receives travel vouchers through the trade unions. The mahallah committees, the bodies of public control and self-government on the level of the traditional quarter (mahallah), organize the older generation. All this reminds me of famous from the Soviet years cotton harvest campaigns, only this time the focus of public policy is not the collection of raw materials for light industry but bringing the new industry to global level.

A Jewish house on Tukai Street

Bukhara is much more interesting of the stereotyped perceptions about the former Soviet 'East' with rice pilaf, dried fruits, blue mosaics and blank walls of residential neighborhoods. Walking here, you find lots of interesting details. It turns out that many families of native residents of Bukhara (Uzbeks by ethnicity) still speak the Tajik language at home. It is a trace that was left from the separation of the settled Iranian-speaking population and the steppe Turkish population that existed in Central Asia under Tamerlane and later.

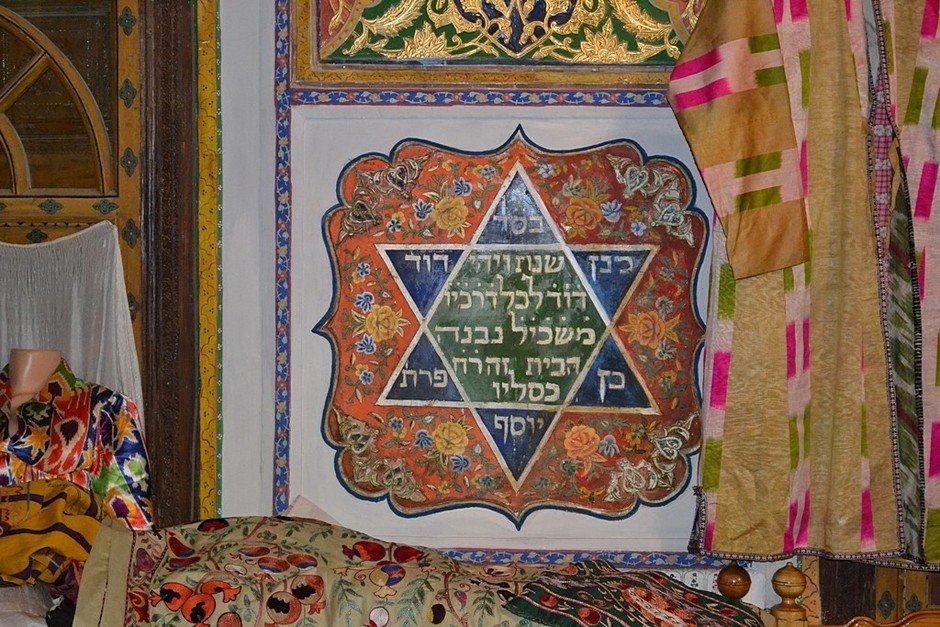

An interesting city attraction is the Jewish quarter of Bukhara, from where a separate ethnic group of the Jewish people originate — the Bukharian Jews. Most Bukharian Jews left for Israel and other countries, but the synagogue, existing since the XVI century, operates until today. On the outskirts of the Jewish quarter on the street of Abdullah Tukai (as local write) there is the house of a wealthy merchant, with well-preserved interiors. In Bukhara style on the carved gallery there are placed colored teapots, bowls and other cooking utensils, and the Star of David with Hebrew inscriptions.

Nearby there is a Tatar caravanserai, where Tatar merchants stayed, thanks to whom the relations between Russia and Bukhara were maintained. But if you go on a tour to the Ark citadel, they will tell you that since the beginning of XVII by the end of XVIII century it was ruled by khans-Chingissids, who fled from Astrakhan occupied by Ivan the Terrible.

Each of the shades of the history of Bukhara can attract its audience. Judging by the way the local authority has taken up the matter, the effect will be tangible pretty soon.

To be continued