Kazakh cinema: from the village and traditions to the topic of domestic violence and YouTube journalism

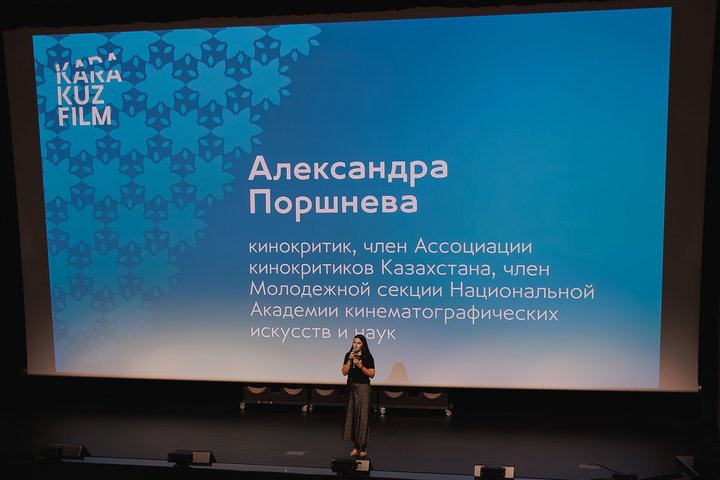

At Karakuz Film, film critic from Kazakhstan Alexandra Porshneva gave an overview of Kazakh cinema

For most people born in the Soviet Union, Kazakh cinema is associated with Kazakhfilm film studio, where the famous films Wait for Me based on the novel by Konstantin Simonov and The Needle starring Viktor Tsoi were produced. But today Kazakh cinema is completely different. It is bigger, more diverse, poignant. It is audacious, social and politicised. In Almetyevsk, at the Karakuz Film International Festival organised by the Academy of Digital Creativity, Alexandra Porshneva, a film critic from Kazakhstan, told what modern Kazakh cinema consists of and also gave a list of recommendations for viewing.

“Energetic, impetuous, unrestrained and fierce”

At first glance, it may seem that Kazakhstan and Tatarstan are culturally and mentally similar. We speak languages from the same group. From this we can conclude that the trends of modern culture are similar in our country. But experts believe that this is not entirely true.

“Kazakh culture differs from Tatar culture, despite that Kazakhs and Tatars are Turks who have a lot in common: devotion to the land, traditions, roots, in a good sense of the word, easterness. It seems to me that Kazakhs are by nature more energetic, impetuous, unrestrained and fierce. Kazakh cinema is distinguished by this: drive and nerve, which is not present in Tatar cinema. Because the Tatars are more sedate, calm and composed. Since Tatarstan is a part of Russia, and Kazakhstan has long been a separate country, their cinema is developing according to different rules and standards," Adilya Khaibullina, a film critic, Honoured Worker of Culture of the Republic of Tatarstan and program director of the Karakuz Film Festival, told Realnoe Vremya.

Certainly, Soviet heritage played a big role in Kazakh cinema. But more than 30 years have passed since that moment. And today, the film product of Kazakhstan is a non-linear, multi-layered, complex and interesting cinema. Film critic Alexandra Porshneva said in her speech that genre and mass cinema is now at the top of Kazakh cinema, and author's cinema is slightly lower, which is starting to step on the heels of genre cinema. Documentaries occupy the third place, and animation is the weakest link in this list. However, Porshneva is sure that this segment will soon receive its development.

Mystical, comical, authentic villages and towns

In order to better understand modern Kazakh cinema, Alexandra Porshneva spoke about the main symbols and images that play an important role not only in national cinema, but also in local identity. And the first image is space.

“Space is what defines our consciousness. This is latitude, steppe and, of course, an aul, that is, a village. It is interesting how the image of the village has been transformed over the course of almost a century of Kazakh cinema history. It reflects the state of society, the country and the main characters. In Kazakh cinema, several states of the aul can be distinguished. For example, the aul is like memories from childhood. This is usually a very elegiac, subtle, almost transparent, melting feeling of childhood," Alexandra Porshneva said.

- My Sister Lucy (Ermek Shinarbayev, 1985).

- My House on the Green Hills (Asya Suleeva, 1986).

- A Gift to Stalin (Rustem Abdrashev, 2008).

- Seker (Sabit Kurmanbekov, 2009).

The aul is also the reality that surrounds the Kazakhs. This reality is tangible, filled with real heroes and problems. Sometimes in films it is shown convex and exaggerated. But the life of the village, according to Porshneva, determines the national identity.

- The Tracks Go Beyond the Horizon (Mazhit Begalin, 1964).

- Atameken (Shaken Aymanov, 1966).

- Zhylama (Amir Karakulov, 2002).

- Tulip (Sergey Dvortsevoy, 2008).

There are also negative images of the aul in Kazakh cinema. Sometimes it is presented as an illusion. Not a mirage, but a real place, but in some way caricatured and stereotypical.

“This does not mean that we treat this side of the image of the village in a negative way. It seems to me that it is important to understand and accept all the phenomena and reflections of the image of the village in the cinema. Because it transforms and comes to a completely new quality," Alexandra noted.

- Zhauzhurek. Mynbala (Akan Sataev, 2011).

- Kelinka Sabina (Nurtas Adambai, 2014).

- Escape from the Aul. Mahabbat Operation (Nurtas Adambai, 2015).

Another image of the village is a mystical, scary and otherworldly village. It usually refers to Turkic mythology and worldview. In this case, the village becomes almost an underground world, a world of death, fear, and intimidation. This is the image of the village as an anti-world.

- The Needle (Rashid Nugmanov, 1988).

- Aksuat (Serik Aprymov, 1998).

- Lessons of Harmony (Emir Baigazin, 2013).

- The Lords (Adilkhan Yerzhanov, 2014).

Space is a significant part of the perception of the world and identification in Kazakh cinema. But it is not limited to the aul. There is also a city. But, according to Alexandra Porshneva, it is not so widely represented in the national cinema. Although its main features are identical to the village.

- Elegy: Balcony (Kalykbek Salykov, 1988), Dos Mukasan (Aydin Sakhaman, 2021), Mukagali (Bolat Kalymbetov, 2021).

- Reality: Angel in a Tubeteika (Shaken Aimanov, 1969), Blocks (Akan Sataev, 2016), Personal Growth Training (Farhat Sharipov, 2018).

But Alexandra Porshneva did not give specific film recommendations to the city as an illusion. She only noted that such an image can be found in hundreds of modern films.

“There are a lot of films now where the action takes place in the city and against the backdrop of urban landscapes. There are more and more such films. And I like this trend. Our filmmakers began to respond to different spaces. We are not only in the aul. We lived through this image. And finally we switched to what surrounds us today. Still, for the most part, people live in cities that sometimes become anti-world," Porshneva added.

- The Scheme (Farhat Sharipov, 2022).

- Die or Remember (Ernar Nurgaliev, 2023).

- Brothers (Darkhan Tulegenov, 2022).

“The world of the city and the world of the aul reflect each other to some extent. Because today Kazakhstan exists not only in the space of the aul. We have long moved away from the nomadic lifestyle, but these two worlds do not let us go. And today, people still live their lives between these two spaces," Alexandra said.

Men are gradually fading into the background

The second important point for understanding Kazakh cinema is the image of the character. And here, according to experts, there are no discrepancies with Tatar cinema. More precisely, both Kazakh and Tatar cinema are in line with the global trend.

“In Kazakh cinema, in Tatar cinema, in the world cinema, the hero is looking for an opportunity to integrate into another culture, looking for a dialogue with the wider world and other people. It should be noted that female images are now coming to the fore. At the same time, men still remain the central characters, unlike in European or American cinema," film critic Adilya Khaibullina commented to Realnoe Vremya.

Alexandra Porshneva believes that the hero is a direct reflection of the state of society. His transformation takes place as time goes by. Therefore, gradually the male hero in Kazakh cinema fades into the shadows. However, as Adilya Khaibullina noted, he is leaving, but he has not left. The most striking male image is a batyr, a warrior who reclaims not only his native land within the framework of historical and revolutionary genres, but also reclaims his business, space, family and dream. Batyr is still a vivid role model in Kazakh society. He builds a family and a space around himself, lives in a city or in an aul, builds his own life the way he sees it.

- Dos Mukasan (Aydin Sahaman, 2021).

- The Paralympian (Aldiyar Bayrakimov, 2022).

In addition to batyr, the image of the rebel character is also popular, which became iconic in the incarnation of Viktor Tsoi in the film The Needle. A rebel is a person who goes against society and the system. Kazakh cinema could not do without the image of a loser — a man who is lost in time and space. By the way, this type of hero appeared in the late 80s and early 90s. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the loser hero was left alone not only with problems. He was trying to understand who he was in this new state, what kind of state it was and what it consisted of. And also the image of the antihero and the image of the father occupied their niche in the cinema.

- The Rebel: The Needle (Rashid Nugmanov, 1988).

- A loser: Aksuat (Serik Aprymov, 1998), Little People (Nariman Turebaev, 2003).

- Antihero: Black Black Man (Adilkhan Yerzhanov, 2019), Personal Growth Training (Farhat Sharipov, 2018).

- Father: Atameken (Shaken Aimanov, 1966), From (Aizhan Kassymbek, 2020).

“A woman is going on the big stage in the Kazakh cinema today. And not only in the cinema. In principle, society has begun to pay attention to the role of women. This image has also gone its own way. Here we can note the image of the mother and kelin, that is, the daughter-in-law," Alexandra Porshneva said.

- Mother: The Tale of the Mother (Alexander Karpov, 1963), Angel in a Tubeteika (Shaken Aimanov, 1969), Footprints Go Beyond the Horizon (Mazhit Begalin, 1964), The Road to the Mother (Akan Sataev, 2016).

- Kelin: Traces Go Beyond the Horizon (Mazhit Begalin, 1964), Kelinka is Also a Human (Askar Uzabaev, 2017), Kelinka Sabina (Nurtas Adambai, 2014).

If the problems between mother and daughter-in-law are an eternal topic, then in the 1990s another image of a woman appeared — femme fatale. A woman in this period is not just a daughter-in-law, not just an actor and not just sets off the main character. She becomes the driving force. A woman begins to understand her value and put her own interests above the interests of a man. In this regard, she is a femme fatale. And there is a downside, according to which she continues to be a woman in fact — with her feelings, pain and worries.

- Femme fatale: Razluchnitsa (Amir Karakulov, 1991), Station of Love (Talgat Temenov, 1993).

- A woman in fact: Touch (Amanzhol Aituarov, 1989), The Needle (Rashid Nugmanov, 1989), Yellow Cat (Adilkhan Yerzhanov, 2020).

“And the last vivid female image in the movie is a warrior and a defender. It is used in a very interesting and diverse way by our cinematographers. On the one hand, these are such marketing pictures about our nomadic culture. On the other hand, a woman becomes the mouthpiece of society, problems, and pain. She screams that we cannot continue to live like this, that we can no longer tolerate violence against our children, we cannot turn a blind eye to the murder of children. And she's fighting it to the end," Porshneva said.

- Zhauzhurek. Mynbala (Akan Sataev, 2011).

- Tomiris (Akan Sataev, 2019).

- The Black Black Man (Adilkhan Yerzhanov, 2020).

Separately, Alexandra Porshneva noted the film by Askar Uzabayev Bakyt/Happiness. This is an acute social drama about domestic violence, which has excited the Kazakh society. The idea of the film is that a woman is also a human being, she should live in comfort and safety. In Bakyt, the main character tries to win back this space. But she fails. But the Kazakh society succeeds.

“I think that the film Bakyt played a big role in the fact that this year we adopted a law toughening penalties for domestic violence and pedophilia. Because while watching this film, many people were leaving the cinema. They could not look at the brutal scenes of beating a woman, of violence against her. And all this horror took place in warm home interiors, in a space that should be filled with love and family warmth. The viewer caught this story very sensitively. Attention was drawn to domestic violence. They started talking about what it is," commented Alexandra Porshneva.

Another important image in the palette of heroes is a child, who often acts as a reflection of an adult. But besides that, he represents a generation, he replaces infantile adults and becomes an adult himself. And the child is also an indicator of society.

- The personification of a generation: My Name is Kozha (Abdulla Karsakbayev, 1963).

- An adult child: Mountain Bow (Eldar Shibanov, 2022).

- The indicator of society: The Wounded Angel (Emir Baigazin, 2016).

Tragic family, spectator escapism and gang theme

Again, if we compare Kazakh and Tatar cinema, then we differ greatly in the choice of subjects.

“If we talk about themes, the theme of social norms, standards, and injustice is obvious in Kazakh cinema. This is not yet the case in Tatarstan cinema. We talk more about our traditions and about today's life. In my opinion, cinema in Kazakhstan is more politicised and genre-diverse. It is more poignant in its utterance, more daring. And we are softer," said Adilya Khaibullina.

But Alexandra Porshneva noticed that at least one topic coincides with ours. This is the theme of family and home. Porshneva said that modern filmmakers are actively developing it, especially when it comes to financing from the state. But the problem with such paintings is that they turn out to be too glossy. But in the author's film, the theme of family and home is tragic and highly social in nature. And also family and home exist in the connection of space and heroes, who either always conflict or unite and resonate with each other.

- In a tragic and highly social context: Maryam (2019, Sharipa Urazbayeva), Nagima (2013, Zhanna Isabayeva).

- In the connection of spaces and heroes: Atameken (1966, Shaken Aimanov).

- In the conflict of heroes with space: The Needle (1988, Rashid Nugmanov), Black, Black Man (2019, Adilkhan Yerzhanov).

In Kazakhstan, filmmakers turn to the theme of the past, which they try to comprehend through biopics and historical films. But their view of the present looks the most interesting, which often stimulates spectator escapism. These are usually household comedies that people come to in order to disconnect from the real world with its problems. But the future in Kazakh cinema is represented through the understanding of the past and the present. In such films, they usually try to analyse and comprehend the problems of society and the problems of the state level. And a separate place in Kazakh cinema is occupied by the gangster theme, to which some directors devote almost all their work.

“Comedies and dramas have been dominant for a long time. But now they are gradually fading into the background. Genres are often mixed. Finally, horror and ethnohorrors appeared. This is also symptomatic of the feeling of society and the tension present. In this way, what is happening is being rethought. And there is also a study of the problems of society through folklore images," Alexandra Porshneva commented on the genre diversity.

YouTube journalism has revived documentary films

Everything that Alexandra Porshneva told me concerned feature films. But there were certain difficulties with the documentary. In the 1990s, it practically disappeared, or rather, switched to the format of TV shows. Then in Kazakhstan, television began to produce a huge amount of documentary content that was not of high quality. This continued until 2016, when the YouTube investigation of Kanat Beisekeyev's The Ball came into view. This is a story about Kazakhstani children adopted by foreigners. Beisekeyev made a film about how these children assimilate and lose their national identity.

This video has spread all over the Internet. And the Kazakhs then realised that documentaries are not TV shows when they tell about the lives of famous people (although this is also important), not anniversary pictures. People started actively looking for real documentaries and found them on YouTube. Now, according to Porshneva, the documentary is actively developing at the expense of young authors. For example, Katerina Suvorova's work Tomorrow is the Sea became the first Kazakh film to appear in the European segment of Netflix.

“I believe that it will be interesting and diverse next. And it is very important that we observe how this happens, that we analyse it, that we watch a film. It seems to me that our cinematographies — of Tatarstan and Kazakhstan — have something in common both traditionally, in the film language, and even in thematic elements. They are very close to the elements of tradition, comprehension, mentality. It is important that we look at each other, look inside ourselves, look around and be not indifferent to what is happening today," film critic Alexandra Porshneva concluded her speech.

Ekaterina Petrova — literary reviewer of Realnoe Vremya online newsppaer, author of Poppy Seed Muffins (Булочки с маком) telegram channel, and founder of the first online subscription book club Makulatura.