Sylvia Nasar: ''It was incredibly moving to watch John Nash get his life back...''

A Beautiful Mind's author in an interview with Realnoe Vremya

Realnoe Vremya has recently published a review of Sylvia Nasar's A Beautiful Mind, which is a book about genius mathematician John Nash's incredible fate. A Beautiful Mind directed by Ron Howard with Russell Crowe's brilliant acting was based on the book. It should be reminded that the book saw the light of the day in October 2016 at Corpus on the initiative of Evolution Educational Fund and thanks to a donation of people who support science and education. Together with Evolution, Realnoe Vremya managed to talk to the author of the book, American journalist, writer and economist Sylvia Nasar.

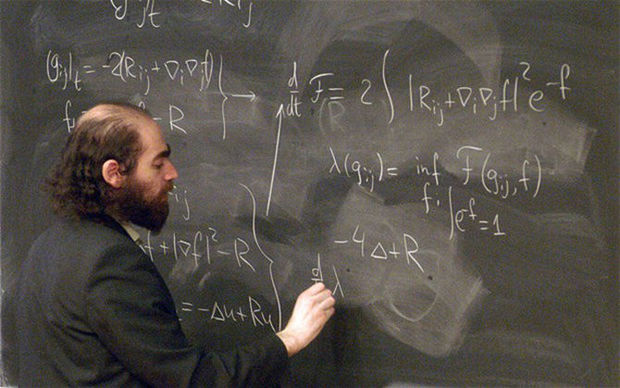

Your book about John Nash A Beautiful Mind and article Manifold Destiny about Russian Grigory Perelman in The New Yorker speak about the nature of the mathematical genius. Neither Perelman nor Nash had a kind of genetic predisposition to genius and grew up in different social systems. But they turned out to be very similar when they made a stab at mathematical problems of the millennium without fear. Did you manage to see in them what differentiates a genius mathematician from a good one?

Interesting that you see them this way. Both were identified as unusually bright as children, were intellectually precocious in their interests, had highly educated parents who stimulated and supported them, and, different social systems notwithstanding, were both fortunate to have first rate educational opportunities. But Nash was identified as a genius long before he had produced work regarded as great by other mathematicians, in fact, while he was still an undergraduate at Carnegie Tech. As a student and later, Perelman was highly regarded by his peers, but my impression was that he surprised the mathematics community when he solved the Poincare. Perhaps this was because Nash was so much more social and engaged with the profession, or because he had so many ideas and worked on so many problems in disparate fields.

''Perelman was highly regarded by his peers, but my impression was that he surprised the mathematics community when he solved the Poincare.'' Photo: telegraph.co.uk

Nash lived for 20 years more after your book was published. What can you say about those years? Did you continue communicating with the Nashes after publication? Would you write a separate book about those years?

John Nash didn't cooperate with me while I was writing A Beautiful Mind, that is, he was perfectly willing to talk at a dinner party or a conference, but he would never grant me an on-the-record interview. After the book appeared, however, he decided he wished to be friends. The first time my husband and I took John and Alicia out, we went to the first Broadway play Nash had ever seen. It was incredibly moving to watch him get his life back… ordinary things, things utterly unremarkable for other academics, like getting a passport and driver's license again, having lunch with the other mathematicians at the Institute for Advance Study, having his teeth fixed, getting help for his son, wearing nice clothes, going out with friends, working on some math problems, having a research assistant, etc. Very few stories have a third chapter. His did. It shouldn't have ended the way it did, but it was a great one.

It is told that after remission Nash could not do groundbreaking scientific research. Is it true? Because he did research. Is it possible that his research was not understood or estimated?

Two points: First, Nash did do some fairly astounding work in the 1960s after he got sick, his illness having had an episodic character initially. Second, he was in his 60s and had not been doing mathematics for decades when he finally experienced a permanent remission. He still had interesting ideas and worked on some of them, but I don't know of any that were comparable to the work he did in his 20s.

Now you are working on a book about 'Soviet collaborationists, spies and agents of influence at the end of the Second World War'. If your previous books were about mathematicians and economists, why did you choose such an exotic topic? Does this topic of betrayal and cooperation with the enemy have anything new? Will people in Russia — a country that is very proud of the victory against Fascism — understand you correctly after that?

You've got your facts wrong: My new book, to be published by Viking/Penguin in the US, is about prominent individuals in the West— not Russia — who collaborated, usually secretly, with the Soviet government from the mid-1930s until the late 1940s… that is, not just during WWII. Please be sure you get this right.

''He was in his 60s and had not been doing mathematics for decades when he finally experienced a permanent remission. He still had interesting ideas and worked on some of them, but I don't know of any that were comparable to the work he did in his 20s.'' Photo: theguardian.com

A number of them were economists which is how I got interested in the topic while I was working on Grand Pursuit. That said, I hope your last question doesn't imply that you think journalists should only write about topics considered politically correct… In history, there are no sacred cows and no subjects about which there is nothing new to say.

Is solution of the toughest mathematical problems a dangerous for mind?

Tackling any difficult problem, in public, and by oneself is potentially stressful, and stress can be destabilizing. But of course causation runs the other way too. Mental illness can destroy scientific careers. The most rigorous studies on this subject suggest that mental illness is more damaging to scientific than artistic creativity. Presumably this has to do with the nature of the work and the training and career paths…

Reference

Sylvia Nasar is an American economist, journalist, writer and Professor of Journalism at Columbia University.

- Born on 17 August 1947 in Rosenheim, Germany

- 1951 — Her family immigrated to the United States of America

- 1970 — BA in Literature from Antioch College

- 1976 — Master's degree in Economics at New York University

- From 1977 to 1980 — She worked at the Institute for Economic Analysis and started to write

- 1983 — Sylvia Nasar joined Fortune magazine as a staff writer

- 1990 — She became a columnist for U.S. News & World Report

- From 1991 to 1999 — Sylvia Nasar was an economic correspondent for the New York Times

- 1998 — She published A Beautiful Mind. The Life of Mathematical Genius and Nobel Laureate John Nash.

- Since 2001 — She has been the first John S. and James L. Knight Professor of Business Journalism at Columbia University

- 28 August 2006 — Sylvia Nasar published an article Manifold Destiny about Russian mathematician Grigory Perelman who solved the Poincaré conjecture

- 2011 — publication her second book Grand Pursuit: The Story of Economic Genius

- Now Sylvia Nasar is giving lectures and writing her third book about ''Soviet collaborationists, spies and agents of influence''.